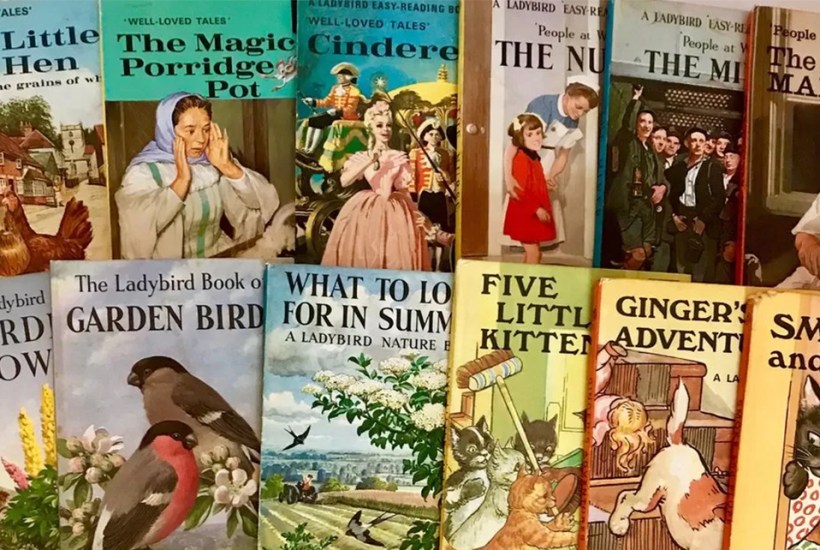

Visiting my family’s house, now inhabited by my sister, the other day, I dug out the heart of my childhood library, my Ladybird Books. They were the only books I bought with my pocket money when I was a small boy. Each short, well-produced hardback cost half a crown (12.5p). I got one old penny for each year of my age. So when I stopped buying Ladybirds at the age of 12, I was laying out two and a half weeks’ earnings on them. Rereading them now, I see how much they excited my imagination. Perhaps because of their link with childhood, they read well at Christmas.

There were many different types of Ladybird books – ones about the farm, or travel, for instance – but the ones I liked the best were called ‘Adventures from history’. The first, published in the year of my birth, 1956, was King Alfred the Great. Usually, they concerned a single historical figure – Florence Nightingale, Captain Cook, Robert the Bruce etc. The format was unvarying, and powerful: a page of text on the left talking to a full-page colour illustration on the right. It is the pictures that have the most Proustian effect of recall – Harold tricked by William into swearing unwittingly over sacred relics; Captain Oates going out into the blizzard; grim Civil War Puritans scowling at maypole dancers. The artist was John Kenney, of whom I know nothing. But the text is powerful too – tightly written, narratively strong and capable of explaining quite grown-up things simply. Monopoly, for example (apropos of Sir Walter Raleigh’s woollen cloth export), is rendered: ‘In those days men were rewarded by being given the right to sell something which no one else was allowed to offer.’ The author of all my books was L. du Garde Peach. Mentioning him in print years ago, I guessed he must have been an anagram, but a reader kindly corrected me: his name was genuine (the L stood for Lawrence), and he was quite a well-known dramatist, Sheffield-born and educated in Exeter (Devonians get highly favourable Ladybird write-ups).

A surprising and impressive feature is that Peach’s stories include something which young children think little about – historical sources. If a story is mere legend – Alfred burning the cakes – he says so. The account of the Norman invasion in 1066 draws on that of ‘the man whose father saw [it]’. Livingstone’s diary of his journeys is quoted directly to describe attacks by the Ajawas (‘They began to shoot their poisoned arrows’) and by a lion. The most notable omissions, of course, are to do with sex. Nelson’s life passes without mention of Emma Hamilton.

At the time, it never occurred to me that Peach had views: I assumed his authority, as children do. Now I see that he was mildly anti-Catholic, strongly pro-Oliver Cromwell and undogmatically in favour of what was then in the process of changing from the British Empire to ‘the British Commonwealth of Nations’. What most excites him is Britons who have great adventures overseas – Nelson, David Livingstone, Raleigh. He thinks as boys think (or thought). Take this first paragraph: ‘Two hundred years ago, a little boy called Horatio Nelson was born in the County of Norfolk, and grew up to be the greatest fighting sailor England has ever known.’ If you are nine years old, you read on. Or take this, on Livingstone crossing hundreds of miles of the waterless Kalahari to Lake Ngami with his young family: ‘This must have seemed like one long picnic to the children.’ What people would now call the ‘narrative arc’ ends up with Elizabeth II, the young Queen who had recently come to the throne. When Alfred entered Winchester Cathedral to be crowned, Peach says: ‘The ceremony of coronation was the same as when our present Queen Elizabeth was crowned, and as it has always been celebrated from that day to this.’ This is not absolutely accurate, but it is true in spirit (and, one hopes, will prove so next May). In Ladybird history, the reign of the first Elizabeth presages that of the second.

Horrors are not shirked – Cromwell in Ireland, William the Conqueror harrowing the north, Edward I putting the Bruce’s women in cages – but the overall picture is of great things done. England – the word more commonly used than Britain even after the Union – faces external threats and internal divisions, but the individual adventures related add up to the big adventure of English/British history. Empire is not attacked as such, but its evils, such as the shooting of ‘red Indians’ by early colonists, are acknowledged. Peach’s last words on Livingstone are, ‘More important than all, it was due to his work and writings that the movement was set on foot which abolished the slave trade in Africa’.

Although I later learnt to be wary of the Whig interpretation of history, some sense of the positive progress of our country, presumably derived from Ladybird books, has stayed with me. Although I also came to recognise that history involves deep economic, religious, intellectual and social trends, the Ladybird understanding that it is affected and dramatised by great men and women still convinces. Peach concludes his first volume: ‘So England became a free country and we should always remember that it might have been very much less free if Alfred the Great had not lived and ruled, a thousand years ago.’ Obviously, history is more complicated than that. But I am grateful to be old enough to have had my interest kindled in this way. I feel sad if children today are taught to start with shame, not pride.

As I write, controversy continues about Boris’s peerages. I gather that the man himself recently said: ‘I’ve had a brilliant idea: I’ll make Stanley [his father] a viscount and then I’ll run him over.’ I find that when I relay this story to young people I have to explain not only what a viscount is, but also that Boris was making a joke.

The post What Ladybird Books taught me about history appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in