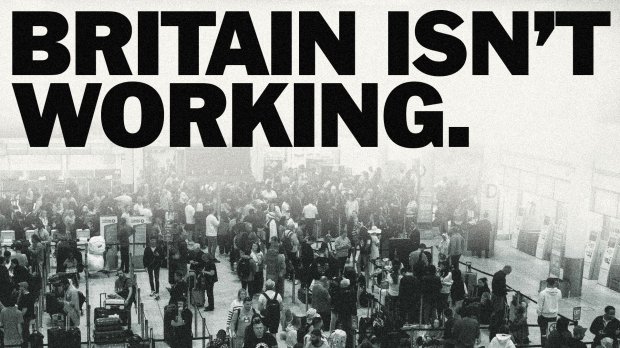

When asked about their religion in a census, many British people have the same response: that it’s none of the government’s business. For a while, as a joke, tens of thousands stated their faith as ‘Jedi’, a fictional order of knights from Star Wars. Nevertheless, this year’s figure marks an important trend: just 46 per cent identified as Christian, down from 72 per cent two decades ago. Muslims are growing in number, but slowly: from 5 per cent of the population ten years ago to 6.5 per cent now. By the next census, those who profess any religion may be outnumbered by those who do not.

The decline of organised Christianity will not surprise those who attend churches, which have been closing at the rate of about four a week. Too many church leaders seem to think their job is managing decline. During lockdown, churches across the country were closed even for private prayer. Church leaders didn’t just support this: some demanded it. If bishops don’t seem to think that worshipping in the pews is an essential part of British life, it’s hardly surprising that the laity feel the same way.

It’s common for Christians to regard the decline of worship – especially among the young – as a sign of a country going to the dogs. But this conclusion is hard to reconcile with the behavioural trends of young people who are, according to pretty much every survey, more studious, conscientious and abstemious than their parents’ generation. Teenage pregnancy is at its lowest rate since records began in 1969 and, in the past decade, the numbers of crimes committed by teenagers have fallen by more than half. An increasingly godless Britain has somehow managed to produce a generation of young people who are better-behaved than their parents.

The trend was anticipated and satirised by Jennifer Saunders in Absolutely Fabulous, the comedy about a louche mother, Eddie, despairing of her austere daughter Saffy, who preferred homework to men. ‘I don’t want a moustached virgin for a daughter,’ she tells her in one episode, ‘so do something about it!’ Secular Saffyism is prevalent in modern Britain. Instead of fretting about moral decay, parents now worry that their children are not enjoying themselves enough.

But no matter how many churches are deconsecrated, we remain a country steeped in Christian values and culture. Britain’s majority-secular young generations believe very strongly in qualities such as humility and charity. They believe in standing up for the persecuted and the sick, in helping people to help themselves – all fundamentals of Christian teaching. We still salute Good Samaritans, we still think the rich have a responsibility towards those less fortunate, and that societies can be judged by how the poorest are treated. We remain suspicious of people who, like the Pharisee in the temple, loudly profess their own virtue.

A generation or so ago, it might have been argued that the rise of Islam or other religions was a threat to our society. But the integration of people of other faiths has been a British success story. Polls show that Muslims are more likely than others to say they are proud to be British. In the rare cases where abandoned churches have become mosques, the old congregations have been pleased to see the building preserved for worship – and not turned into a pub. Some Christian and Muslim groups align to campaign on issues such as abortion or the teaching of sexuality in schools.

Mass immigration is slowly giving Britain a new face, if not a new identity. We are moving from a country with an explicitly Christian government to one with a government rooted in certain secular, national, unifying principles. The Home Secretary, who is Buddhist, is attacked for all kinds of reasons but not for her faith. The Prime Minister has a Hindu shrine in No. 10 and no one minds. It’s hard to imagine the same thing happening in America.

The Book of Common Prayer has bequeathed many phrases to everyday life, as has the King James Bible. Phrases such as ‘by the skin of his teeth,’ ‘the writing on the wall’, ‘like a lamb to the slaughter’ are used without any consideration of their biblical origin. Moral concepts from the gospels have been internalised in our society.

Bemoaning the end of faith is a long British tradition. In his 1851 poem ‘Dover Beach’, Matthew Arnold lamented the ‘melancholy, long, withdrawing roar’ of the ‘sea of faith’ leaving a godless country with ‘neither joy, nor love, nor light’. But as G.K. Chesterton later pointed out, the terminal decline of faith has been proclaimed many times before – and yet faith has a way of rising again, in unexpected ways and at unlikely times.

It is a peculiar British tendency to assert that we have moved on from religion, that we have left everything behind as we seek rationality, that religious belief is now nothing more than medieval superstition. A more rational approach would be to recognise that most of us are still the product of the predominantly Christian culture in which we have been raised – and which unites us still.

The post What the census misses about Christianity in Britain appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in