It’s not often that ex-KGB officers blame Lenin for anything. But in his speech of 21 February 2022, on the eve of his ‘special military operation’, Vladimir Putin rounded on the founder of Bolshevism for creating the artificial Ukrainian state.

‘Modern Ukraine was entirely created by…Bolshevik, Communist Russia,’ he declared; ‘and…in a way that was extremely harsh on Russia…Soviet Ukraine can rightfully be called ‘Vladimir Lenin’s Ukraine’. He was its creator and architect.’

This false line of thought could equally accuse the Bolsheviks of having created the Ukrainian language. In reality, the concept of a separate Ukrainian nation and language long preceded the Bolsheviks. After gestating in Ukraine for over a century, it was embraced, both by Russian liberals during the 1905 ‘Revolution’, and by the Kerensky government that followed the Tsar’s overthrow. It inspired the formation, in March 1917, of the Central Ukrainian Council, chaired by the historian, Mykhailo Hrushevsky. This outfit led the Ukrainian movement from autonomy to independence, publishing a series of key ‘universals’ on the principles of Ukrainian nationality.

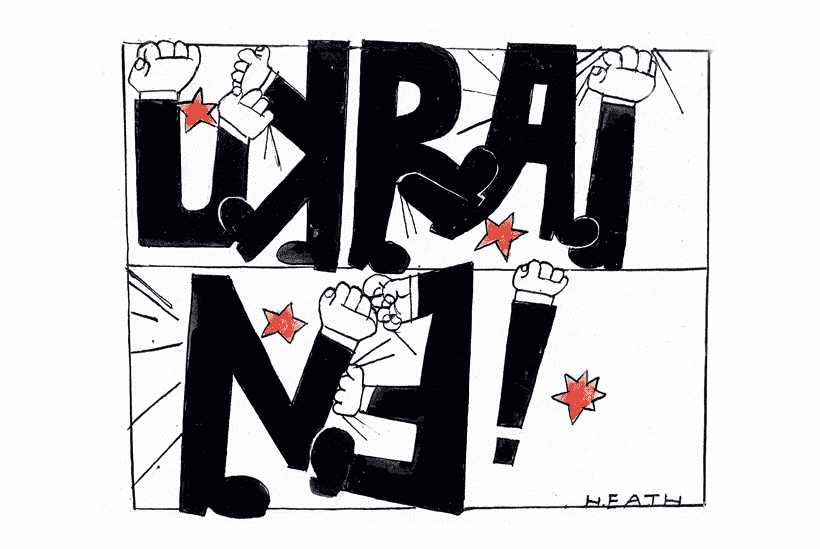

Putin is wrong to suggest Lenin ‘created’ Ukraine

Putin is wrong to suggest Lenin ‘created’ Ukraine

Fiercely denounced as ‘bourgeois deviationists’, many members of the Council were destined to be killed by the Bolsheviks or driven into exile. But before defeat in the Civil War, they established an independent and sovereign Republic of Ukraine that lasted from January 1918 to December 1921. The Ukrainian Soviet Republic, subsequently organised by Lenin, seized power by force of arms. A founder member of the Soviet Union, it overturned Ukrainian independence, subjecting the country to centralised, totalitarian party rule from Moscow. Far from creating the first emanation of modern Ukraine, Lenin destroyed it.

Poland watched in horror. In April 1920, the Polish Army joined forces with Ukrainian allies to drive the Bolsheviks from Kyiv. But within months, they faced a huge Red Army at the gates of Warsaw. Had they not rallied, and driven the invaders back, Poland and Ukraine would have suffered the same fate.

During the seven decades of Soviet Communist rule between 1921 and 1971, the pendulum of language policy swung back and forth wildly. In the 1920s, the Bolshevik leaders took an unexpected turn. Identifying Great Russian chauvinism as the principal enemy and bidding for the allegiance of numerous non-Russian peoples within their re-constituted empire, they introduced what they called korenizatsia, usually translated as ‘indigenisation’ or ‘nativisation’.

Their idea, while Moscow kept overall executive control, was to hand over wide swathes of cultural and administrative action to local non-Russians. In Ukraine, it took the form of ‘Ukrainianisation’. Under Mikola Skrypnyk (1872-1933), ‘Lenin’s man in Ukraine’, the Ukrainian language was installed in schools, universities and offices. Even Russian speakers were ordered to learn it, and party cadres were opened up. As some suspected, it was too good to last. ‘Ukrainianisation’ was easier said than done. Establishing a uniform Ukrainian alphabet, for example, caused endless problems as numerous orthographic systems competed. The Kulishivka (1858) and Drahomanivka (1875) were based on Serbian Cyrillic; the Zhelekivka came from Austrian Galicia; the Russian-based Yaryshivka had emerged in 1905. Skrypnyk’s Skrypnykivka only gained acceptance in 1928.

Two years later, Pavel Postyshev (1887-1939), ‘Stalin’s Man in Ukraine’, arrived to reverse Ukrainianisation, at a time when the maverick Georgian linguist, Nikolai Marr (1865-1934) was upending language policy. Marr’s Japhetic theory raised many eyebrows; his new brand of Marxism, that transferred language from the all-important socio-economic foundations to the social ‘superstructure’, facilitated both the proscription of independent Marxists and the return of russification.

In 1932-33, Postyshev – later accused of genocide – was conducting the Holodomor alongside a mass purge of Ukrainian Communists. Denouncing ‘nationalist deviationists’, he drove Skrypnyk to suicide. After formally banning the letter ‘Ge’, he introduced his Postyshivka script (1936). At the height of the Great Terror, in which Postyshev himself would perish, Stalin re-established the supremacy of Russian. Henceforth, Russian was no longer just the Soviet Union’s lingua franca but ‘the first among equals’, the sole language of the Army command, of higher education, and of the central party cadres. Ukrainian reverted to second-class provincial status.

After Stalin’s death, fearing anti-Russian disorder, the Soviet party partially relented, transferring Crimea from the Russian SFSR to the Ukrainian SSR in 1954 in a conciliatory gesture. On the language front, it sought uneasy compromises. Selective Ukrainian heroes and proletarian Ukrainian writers were celebrated. A drip-feed of Stalin’s crimes revealed some of Ukraine’s horrendous experiences, but not the Holodomor. Yevgeni Yevtushenko (1933-2017), a Siberian-born Russian poet with a Ukrainian name, became one of the foremost voices of Krushchev’s ‘Thaw’; his poem Babi Yar (1961), predicated on the Nazi genocide of Ukrainian Jews, exposed both the prevalence of antisemitism and the profound distortions of Soviet history in general.

But relaxation was limited. The party put its faith in the longed-for growth of all-Soviet patriotism. In 1974, Leonid Brezhnev, born near Dnipro in Ukraine, boldly pronounced the ‘nationalities question’ resolved. He was spitting in the wind. Fourteen of the fifteen Soviet republics were simply biding their time. Their opportunity came a decade later with Gorbachev’s Glasnost; and in 1991, every one of them, including Ukraine, freely chose to part company with Russia. This is what Putin meant by describing the Soviet Union’s collapse as ‘the major geopolitical catastrophe of the century.’

The key law, which made Ukrainian the sole, official language in Ukraine was passed in October 1989, two years prior to the USSR’s demise. A child of glasnost, which was encouraging several other union republics, especially the three Baltic states, to secede, it balanced ‘re-Ukrainianisation’ with protection for other languages, including Russian. In doing so, it removed the sting of potential conflict. This helps explain why the great majority of Ukraine’s Russian-speakers were content to support the referendum on independence in December 1991.

At the end of the Soviet period, roughly two-thirds of Ukraine’s population of 53 million spoke Ukrainian and one-third Russian. Yet there was much bilingualism, and about 20 per cent in their everyday lives spoke Surzyk – a sort of Creole based on Ukrainian larded with Russian vocabulary.

The Republic of Ukraine duly joined the United Nations. It was formally recognised by Russia in the so-called Budapest Memorandum of 1994, whereby Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan surrendered their stock of ex-Soviet nuclear weapons. That process was completed under US supervision by 2008, though a few ‘nukes’ may have been retained. The Ukrainian Constitution of 1996 confirmed the provisions of the 1989 language law, and few doubts about it were expressed during Boris Yeltsin’s presidency in Russia and Vladimir Putin’s first terms of office. The language front in Ukraine remained calm, especially after the victory of democratic parties during the ‘Orange Revolution’ in 2004-5.

Ukraine’s main problems were economic, social, political and, through declining population, demographic. Disputes over language only re-surfaced when the ex-Communist, Viktor Yanukovich, governor of the Donbass, gained control of the presidency in 2010. Benefiting from Putin’s third term of office in Russia, Yanokovich’s Party of the Regions railed against the alleged discrimination of Russian-speakers; in 2012, it introduced a new language law, that gave Russian special status wherever a majority of citizens so demanded. The law provoked a bare fists’ brawl in parliament and a constitutional challenge from the Supreme Court. Nonetheless, a dozen major cities took the opportunity to declare themselves Russian-speaking enclaves: they were Kharkiv, Luhansk, Donetsk, Krasny Luch, Dnipro, Zaporozhia, Kherson, Mykolaiv, Odessa and Sevastopol.

The language issue was well alight, therefore, before the ‘Revolution of Dignity’ broke out in 2014. Nearly 200 people were killed in disturbances, preceding the flight to Russia of Yanukovich and Putin’s undeclared war on Ukraine. Russia’s detailed international aims have never been clearly aired. But the immediate annexation of Crimea, the underwriting of the self-styled People’s Republics of Luhansk and Donetsk, and the particular areas, where Russian forces have been concentrated since the illegal invasion of February 2022, confirms the obvious. Russia’s top priority is to ‘protect’ – that is, to swallow up – Ukraine’s Russian-speaking regions.

Since 2014, Ukrainian politics have passed through three phases To begin with, the ring was held by president Petro Poroshenko (born 1965), who successfully upgraded Ukraine’s defence forces for a major showdown. After the election of 2019, the baton passed surprisingly to the Russian-speaking ex-TV comic, Volodimyr Zelenskyy (born 1978), who has proved himself a substantial international figure. Having waited for the Supreme Court to condemn Yanukovich’s language law, he brought in yet another piece of legislation, that essentially re-instates the linguistic arrangements pertaining since 1989.

Of course, Putin’s full-scale invasion has put an end to all language debates, as all Ukraine’s citizens, with few exceptions, put their shoulders to the wheel of resistance. Nonetheless, it is a great irony that most of the civilians maimed, arrested, deported, robbed, raped or killed by the invaders, have been native Russian speakers.

Now, following Ukraine’s successful counter-offensive, and Putin’s desperate response in annexing four Ukrainian oblasts, the world awaits what happens now. Putin may think he is consolidating Russia’s borderland. Ukrainians of all stripes can recognise a shameless, Leninist-style land grab for what it is.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in