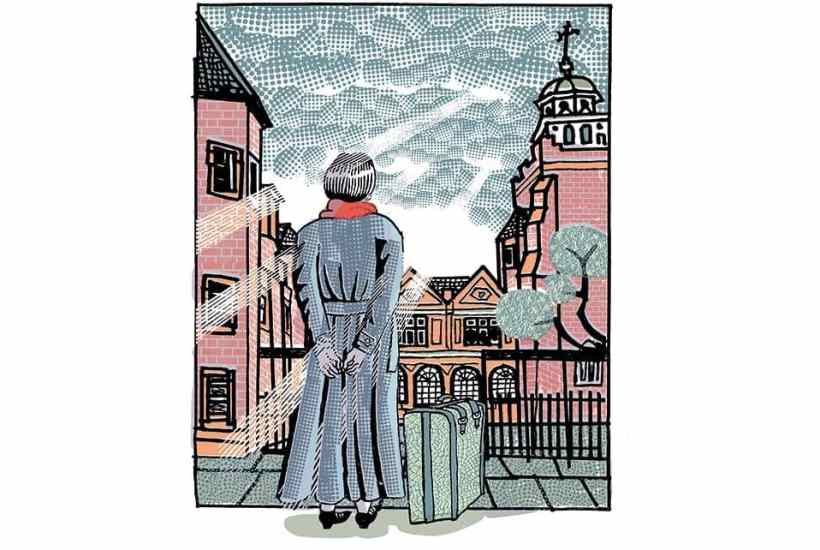

A year ago, I moved into what I hope will be my home for the rest of my life. I became an almshouse resident. The announcement of my implied reduced circumstances provoked some interesting responses: from family, joy that my recent hard times were over; from acquaintances, a range of reactions: embarrassment, shocked disbelief, scepticism. Even some thinly veiled envy. Who’d have thought?

What kind of person ends their days in an almshouse? The key word is need. It might be financial, it might be social, perhaps both. Some people are quite alone in the world. Some reach old age with a negligible pension, or no roof over their head. My own story was the result of a perfect storm of disasters, a confluence of my husband, beset with early-onset dementia, needing expensive full-time care just as I was let go by my publisher and my career went into free fall. To misquote Wilkins Micawber: ‘Two moderate freelance incomes, result, felicity. Sudden reduction of income to zero, result, misery and terror.’

This was the point at which I thought of a very special almshouse, the London Charterhouse, and though I mistakenly assumed I had little chance of being awarded a place there, I began the application process.

Three years on, here I am, a Charterhouse Brother. Some days I pinch myself. But even more surprising has been other people’s perceptions of my turn of fortune.

First, there have been the frankly embarrassed. For some, it is as though by effectively admitting to penury I have violated a taboo. Just as a bereavement can leave sincerely sympathetic people tongue-tied, so, I’ve discovered, does relocation to Queer Street. What can they say? ‘So sorry. We had no idea.’ Or ‘I do wish you’d said. I could have let you have a few quid.’

I imagine this reaction will be familiar to anyone who has been made bankrupt or served time in prison. Old affection becomes seasoned with pity. No one wishes to see a friend brought low, but politeness prevents people from satisfying their morbid curiosity. Exactly how bad is ‘bad’? In some cases, I’ve even detected a bat-squeak of alarm. ‘Gosh, if it could happen to her… We’d better get on the blower to our financial adviser.’

Then there have been the ostriches. A multitude of deniers who convince themselves that if they don’t wish a thing to be true, it will cease to be so. ‘But you’ve been a successful writer,’ they protest, tumbling blithely into the trap of the J.K. Rowling fallacy. They are under the impression that all writers earn vast amounts of money. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Being a mid-list writer was once a perfectly respectable position. You might not set the publishing world alight and readers didn’t queue around the block to meet you, but you reliably produced a book every 18 months, and libraries and your friends always bought it. Those kind of authors may now find themselves cut loose, because publishers are ravenous for the Next Big Thing and, let’s face it, at 75 you are not it.

I feel sympathy for some of my deniers. If they have never been freelancers, I can excuse them their delusions. But not fellow travellers. We chose freedom and that included the freedom to fail. I may have been the first of my writer acquaintances to feel this chill wind, but I certainly won’t be the last. If any grandchild of mine expresses the ambition to be a novelist, I will advise them first to become a fully qualified plumber.

I have also encountered people so astonished at my recent good fortune of finding sanctuary that they suspect me of nefarious malingering or shameless string-pulling. Mercifully, they are few in number, but I see them coming a mile off. The narrowed eyes, a challenging tilt of the chin.

‘Good heavens,’ said one well-heeled matron on learning of my new address. ‘The Charterhouse! How on earth did you manage to swing that?’ Subtext: ‘You jammy blighter.’ Would she have been less rude, I wonder, if I’d been wearing gruel-stained rags? If the sole of my ancient shoe had been flapping or I looked in need of a square meal?

It is true that I have landed in a Rolls-Royce of almshouses, but by no means did I blag or call in any favours to, as she so charmlessly put it, swing it. I was stung by her tone and, as strong drink had been taken, the reply that would normally have occurred to me hours after the event sprang readily to my lips.

‘Destitution,’ I said. ‘Widowed and destitute after a lifetime of working.’

Not exactly esprit de l’escalier, but it was enough to make her clutch her pearls and move away in search of a canapé. Had I, usually a well-mannered person, turned into a chippy pauper or was it simply that I had uttered the dreaded D word and so was an embodiment of that basic human fear of losing everything? Indigence made flesh.

It is true we bring nothing into this world, but there is a very natural desire to hang on to the IBM shares and the little place in the Dordogne until the coffin lid is screwed down. I haven’t lost everything. I have my family, my health, my books, my piano. That said, I am now the beneficiary of charity, which is never a comfortable experience. Pride and all that.

I have to remind myself that I am not where I am because of fecklessness, indolence or useful connections. Nor am I lolling in a power recliner, being spoon-fed on royal jelly. Like all almshouse pensioners, I pay my rent according to my means and I find ways to contribute to the community I live in. I sing for my supper. Still, I can confirm that it is definitely easier to give than to receive.

I like to think that in my small circle I’ve banished the taboo of admitting to hardship. If I’ve also rocked a few assumptions about financial security and deflated any tendency to I’m-all-right-Jackery, so much the better.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in