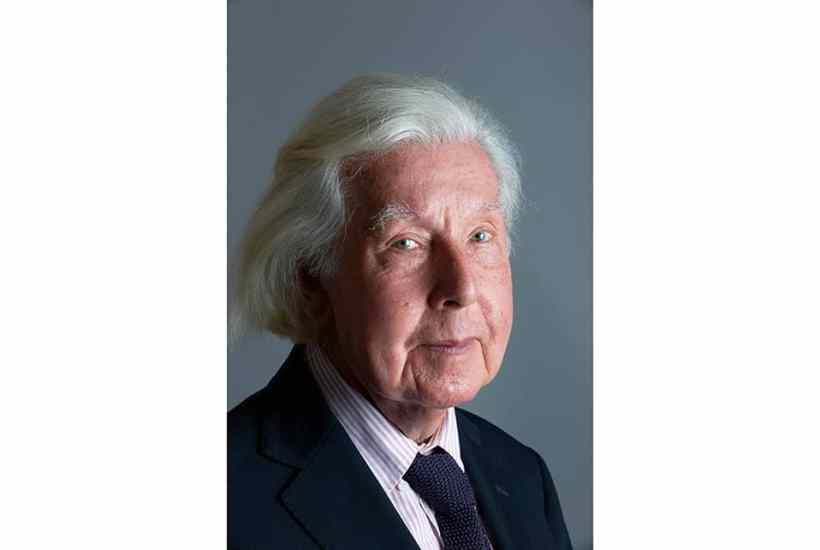

Ronald Blythe, the celebrated author of Akenfield, is to turn 100 next month, and to mark his centenary a beguiling calendrical selection has been made of his ruminations for the Church Times, for which as a lay reader he penned a weekly ‘Word from Wormingford’. It is distilled from 25 years of musings that chase the months from first ghostly intimations of snow at New Year to the blaze of the fire at Wood Hall’s mid-winter supper, while outside ‘the trees crack and the moon is made of ice’. Coming full circle and anticipating the ever-repeating rhythms of the year, they glance between past and present, sacred and secular and serious and wry in such a way that, to quote Richard Mabey in his introduction, ‘a profundity by an Apostle can shade into anxieties over a fish pie’.

Shading, glancing – yes, Blythe’s writing here is agile, light in tone and brimming with playful possibilities and allusions, which is not to say that it is not deeply serious and learned, too. Within moments of embarking on January’s dark days we are in the company of Dr Johnson making and breaking his New Year resolutions (‘like some January fool’); watching George Crabbe plant snowdrops; learning that Gilbert White’s Selbourne jackdaws were reduced to building their nests in rabbit burrows for lack of church towers of sufficient height; and that Laurence Sterne thought ‘writing is but a different name for conversation’.

Blythe’s own writing is warmly conversational and engaging, if never confessional. It is nevertheless revealing, and conjures a sensibility deeply attuned to the natural world, a catholic spirituality, and a complete lack of self-importance. This is a writer who has elevated pottering to an art:

I write a bit, then wrap up, go out… come in, type a page or two, read a chapter, listen to a story on the radio, water hyacinths, answer letters and call it a day. For such is the literary life. All go.

Blythe inherited his house from his friends John and Christine Nash on the border of Essex and Suffolk, not ten miles from where he was born into a family of poor farmworkers. It was not so far from Aldeburgh, where he was drawn into the circle of Benjamin Britten, for whom he worked in the late 1950s, and the artists’ colony around the painting school run by Cedric Morris and Lett Haines near Hadleigh. But for half a century his life has revolved around Wormingford, and the rhythms of the agricultural and church year, distilled into dispatches that for all their apparent ordinariness are often suffused with the extraordinary.

It is this quality that has drawn an impressive group of writers to preface each monthly section, bringing their own brief perspective on Blythe. Among them are Rowan Williams on the ancestral resonance of his winters; Alexandra Harris on his visual rhymes, ‘made with the swiftness of the metaphysical poets’; Olivia Laing revelling in ‘the steady, perpetual listening that gave Akenfieldits power’; Robert Macfarlane on the generosity of his connections; and Julia Blackburn on his ability to ‘move seamlessly as a ghost between time past, time present and even time future’.

Blythe plainly inspires affection, as well as respect for his many decades of diligent reporting from the heart of rural England and from the core of a community threatened by the accelerating pace of change. He never hectors, but summons ages when the blood was quickened by harder, harsher conditions without an iota of sentimentality. John Clare, George Herbert, William Cowper, Francis Kilvert – these are the writers he admires and follows, and their example suffuses his texts. His is a quintessentially English sensibility. His prevailing mood is wonder, so he has no time for conventional likes and dislikes – to him, hornets are welcome visitors, returning ‘time and time again to delight me and terrify the guests’ with their organ-music drone.

This is a capacious book that contains multitudes. It may go over familiar, even repetitive, ground (indeed a section headed ‘The freshness of repeated actions’ opens with ‘Blessed routine…’), but each retelling amplifies the last, stretching the dimensions of its terrain. It is a work to amble through, seasonally, relishing the vivid dashes of colour and the precision and delicacy of the descriptions. As Hilary Spurling points out, Blythe thinks in images (indeed he wanted to be a painter), and there are constant flashes of vision, such as seeing a dazzling kingfisher dart past. It is drenched in humanity and mild, self-deprecating humour. The concluding quote, from Albert Camus – ‘In the depths of winter, I finally learned that within me there lay an invincible summer’ – could not more aptly describe a sensibility that through close attention celebrates the infinite potential of life.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in