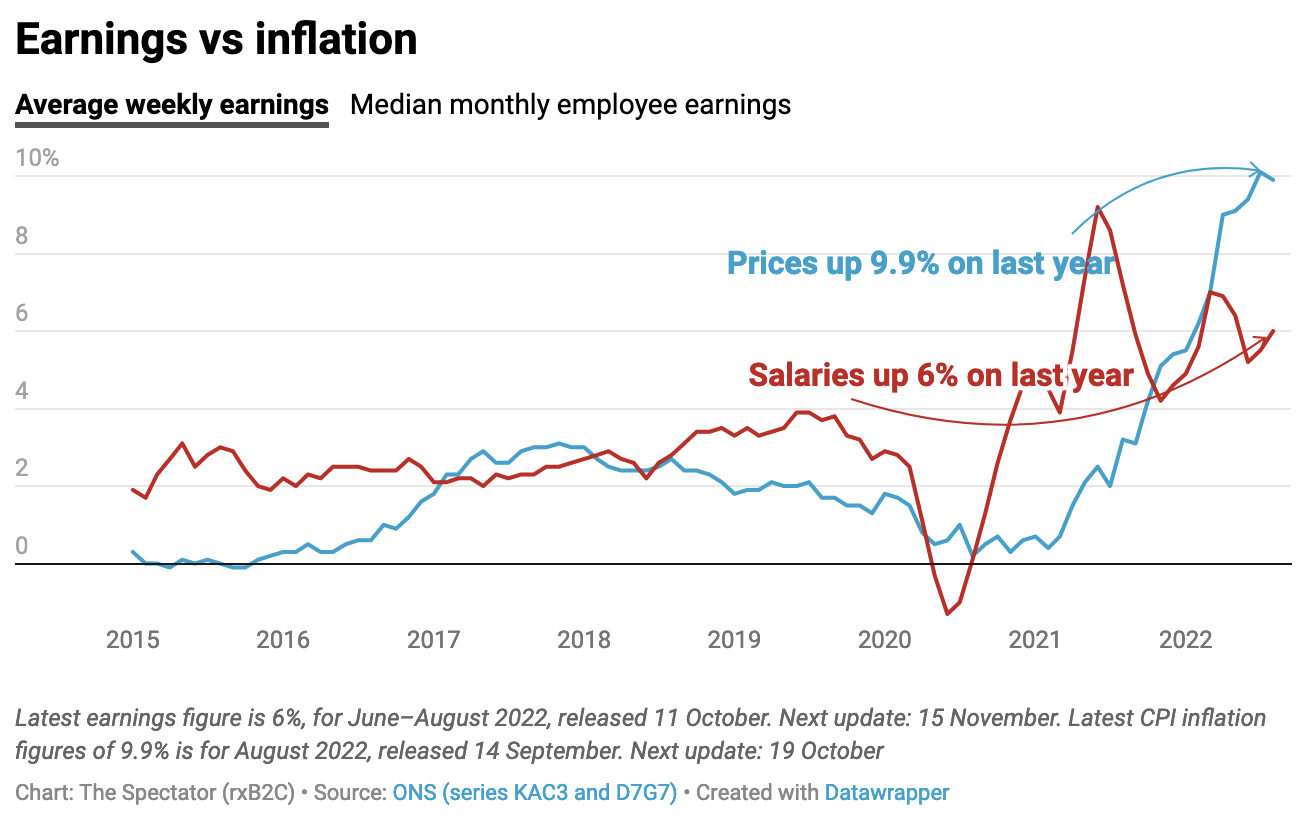

Inflation, asserted Rishi Sunak in his first PMQs, makes us all poorer. That is not entirely true – people relying entirely on the state pension, for example, will be fully compensated for this year’s high inflation, and no doubt some of Sunak’s former colleagues in the hedge fund industry have found a way to profit, too. But generally, he is right. Working people have on the whole suffered a large drop in their real wages.

In the year to April, median weekly pay rose by 5 per cent from £610 to £640. In many years that would be a substantial rise, but when adjusted for inflation it comes out as a fall of 2.6 per cent.

In fact, the situation is likely to be a little worse than these figures suggest because, as the ONS explains, this year’s figures are a little skewed by people returning to work after being on furlough. In accommodation and food services median wages were up 18.7 per cent on the year (before inflation) – not because of a boom in the hospitality trade but because in 2020/21 many of these workers were receiving furlough payments equivalent to 80 per cent of their normal wages, and their wages recovered in 2021/22.

Manual occupations saw particularly hefty rises: 8.6 per cent in the case of process, plant and machine operators and 6.9 per cent in the case of elementary workers. This, too, might have an element of the furlough effect – although low-paid workers have certainly benefited from a shortage of manual workers caused by Eastern European workers returning home either as a result of Covid or Brexit. Professional workers, by contrast, saw an average rise of just 2.4 per cent in the year to April – and that is before inflation.

Public sector unions will no doubt leap on figures showing that average public sector wages rose by 4.6 per cent and private sector ones by 5.9 per cent. But this, too, is a discrepancy related to Covid – during the previous year, 2020/21, private sector wages crashed to negative growth while public sector wages continued to increase. Over the period 2019 to 2022 there has been very little difference between public sector and private sector wage growth.

What is clear, though, is that for the greater part of the working population, real wages, and therefore living standards, are falling. Rishi Sunak has a huge task in convincing the electorate that his government is competent to run the economy, following recent events. But for most people, gilt yields are an abstract concept. What matters far more is whether people feel they are getting better or worse off. And today’s figures show that it is no illusion: high inflation really is impacting on the ability to maintain lifestyles, in spite of nominal wage growth.

The good news is that subdued wage growth indicates that inflationary forces are not yet – or rather, weren’t in April – being recycled through the economy. Workers are not succeeding in bidding up their pay to match the rise in prices. That suggests that we are not in an inflationary spiral, and that the inflationary surge may prove to be more transitory than it was in the 1970s.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in