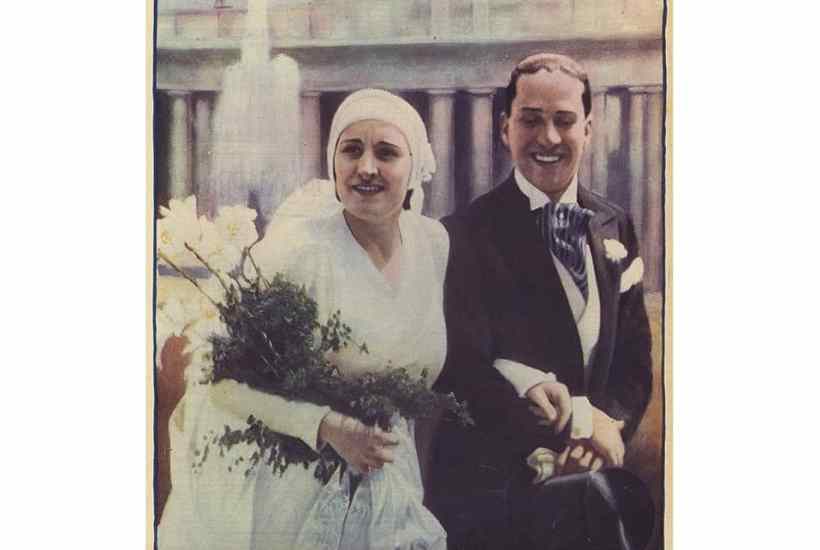

In 1930, when she was 19 years old, Edda Mussolini married Galeazzo Ciano. His father was a loyal minister in her father’s government: it was a suitable match. Five hundred wedding invitations went out to the Roman nobility, to diplomats from more than 30 countries and to all the senior fascists, the gerarchi. After the ceremony the newlyweds left for Capri, Edda driving her own white Alfa Romeo, with servants and luggage following in another car and bodyguards in a third. They set off at top speed. Then Edda came to a sudden halt. She had noticed a fourth car behind them. She might have supposed that as a married woman she was about to get out from under the massive shadow of her father – but no. Following along, unwilling to relinquish his favourite child, came Benito Mussolini, whose rule over his family was as overbearing and ineluctable as his grip on the Italian state.

That day Edda persuaded the Duce to turn back and leave her to enjoy her honeymoon, but she didn’t establish her independence. Journalists dubbed her the ‘most dangerous’ or the ‘most influential’ woman in Europe; but, as Caroline Moorehead candidly admits, it is uncertain how powerful she really was. She had long conversations with her father. ‘They spoke constantly, but just what she said, what she advised, was never written down.’ She was also the wife of the foreign minister, but she and Ciano were at odds. When Mussolini entered the second world war alongside Germany, Edda was ardently in favour of his doing so. Ciano, by contrast, saw intervention as ‘a crime and the height of folly’. It doesn’t appear that Edda’s relationship with him (not a happy one) in any way changed his views.

Mussolini had pinned his hopes on her early. When she was barely old enough to walk she was taken to visit him in prison (he had been arrested for protesting against Italy’s 1911 invasion of Libya – in those days he was a socialist and an anti-militarist). Little Edda, trained by her mother, clung to him as he tucked papers into her pinafore to be smuggled out past the guards. She was afraid of frogs. When she was five, her Papa trapped a frog out on the marshes and forced her to hold it, to teach her that a Mussolini never shows fear.

She grew up wilful. An astute observer described her as being ‘tartly intelligent, capricious as a wild mare and endowed with a thoroughbred ugliness’. As a young woman about Rome in the 1930s, elegantly thin and dressed in slinky gowns, she drank and gambled, losing large sums. She was brusque to the point of rudeness, but as the dictator’s daughter she was the darling of what Moorehead calls ‘the no man’s land where the more adventurous of the nobility joined forces with the energy and excitement of fascism’.

We have heard often (from Moorehead herself, among others) of the experience of fascism from the viewpoint of its victims, or the courageous few who combated it. Here, drawing on the mass of surveillance reports complied by OVRA (the regime’s political police), on the diaries, letters and memoirs of those who partied with fascist insiders and on the notes and correspondence of foreign diplomats in Rome, Moorehead gives us a vividly evocative account of what it was like to live through the two decades of fascism as a privileged intimate of those at the very centre of power.

This is Edda’s biography, but, inevitably, her father’s career looms large in it. Moorehead’s account of Mussolini’s rise and fall is admirably lucid and succinct. Edda is present – her personal story is skilfully interwoven with that of the regime – but often she is upstaged. It is only when she gets away that the book becomes fully focused on her, and it is in those passages that it is at its most interesting and original.

Edda in Shanghai – where Ciano was consul general in the first years of their marriage. Moorehead conjures up a vivid picture of the hectic, cosmopolitan, corrupt city, where the average life expectancy for Chinese was 27; where foreigners danced the Dixieland Swing and the Turkey Trot and envied the Chinese grandees their furs and velvet boots and jade buttons; and where Edda discovered mah jong.

Edda in Capri – where she commissioned a modernist white box of a house and kept a caged jaguar; where she stayed home, wearing dark glasses, and played solitaire for days on end; where she befriended a medium and swam naked off the rocks at night; where Hermann Goering had his nose bitten by a monkey.

Edda in Berlin – where she made friends with Magda Goebbels, counselling her on how to deal with her husband’s infidelities.

Edda in Roman society – in louche circles where her father would not have been at ease; at dinners where everyone was aware that anyone else – a footman, a fellow guest – might be a spy for OVRA.

In conjuring up these settings Moorehead deploys her quotations adroitly, giving us eye-witness accounts from witty observers and introducing each of her large cast of socialites, gerarchi and diplomats with sharp thumbnail sketches. And always at the centre of the crowd, spied on and gossiped about and photographed, moves Ciano (variously described as ‘vulgar’, ‘elegant’, ‘a pompous ass’) and Edda herself – both of them promiscuous (Moorehead is reticent about Edda’s affairs, but acknowledges there were many), both courted, both afraid. There was no point being well-behaved, Edda said, when the guillotine was waiting for you.

And then comes the war and the dreadful denouement. Edda once said she wished only that ‘no one ever hears speak of us again’, but several of her family added to the record by writing memoirs. The title of her son Fabrizio’s book translates as When Grandpa had Daddy Shot. Moorehead writes subtly about the way the two main men in Edda’s life betrayed each other. She allows their motives to be as opaque and ambiguous to us as they probably were to Ciano and Mussolini themselves. Ciano could have abstained from the vote that removed his father-in-law from power and consigned him to prison. Later, Mussolini could have intervened to save his son-in-law from execution. In each case they hesitated, tugged by conflicting impulses of ambition, fear and pride. Ciano was in prison for two months, hoping for reprieve, expecting death. During that time he and Edda, at last, were kind to each other.

Moorehead is a fine writer and a conscientious historian. In her introduction she warns that Edda’s story is so obscured by misinformation and gossip that ‘it is certain that not every incident in this book is true’. But in writing about a regime whose defining practice was self-mythologising, what was believed was as important as what was true. Edda herself chose not to confront facts. Joseph Goebbels thought her extremely clever. If she didn’t see how calamitous for Italy the Pact of Steel would become, it was probably, as Moorehead suggests, because she was determined not to see it.

She lived on until 1995, always ‘strongly denying’ that she had been her father’s éminence grise. Her public role, she insisted, was ‘purely social’. Maybe it was. This vivid, astute book is a reminder that that doesn’t mean she was unimportant. Social history matters. Dinner party chatter isn’t necessarily trivial, especially when the participants have close links to those with absolute power.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in