In all the tributes to Her late Majesty’s constancy, dignity, wisdom and devotion to duty, not enough has been said about her political cunning. But BBC1’s The Longest Reign: The Queen and Her People made a compelling case that Elizabeth II knew just how to tilt the balance.

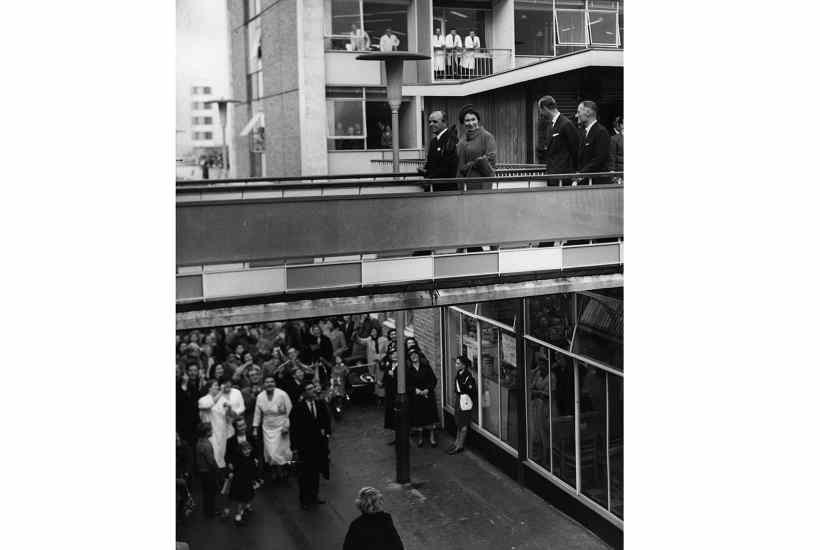

When she toured the new towns of the 1950s (see image), waving at the crowds with their little Union Flags and taking tea with the young families on the just-built housing estates, she was giving her wordless blessing to the welfare state. When she wanted to bolster the No side in the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, her intervention – commenting to a well-wisher outside church that ‘Well, I hope people will think very carefully about the future’ – was exactly calibrated to achieve a kind of decisive vagueness.

Of course Elizabeth II was deft in more everyday ways too. One touching story, often related over the last week, comes from the warzone surgeon David Nott, who when telling the Queen about his traumatic experiences in Aleppo felt himself starting to break down. (‘Perhaps it was because she is the mother of the nation, and I had lost my own mother.’) The Queen opened a box of dog biscuits and invited Nott to help her feed the corgis. As relief washed over him, she remarked: ‘There. That’s so much better than talking, isn’t it?’

Indeed it is, which presented a near-impossible challenge, in those first hours of collective grief last Thursday evening, to anyone whose job is to keep talking no matter what. At times the BBC’s newsreaders struggled to keep bathos at arm’s length, as when Huw Edwards solemnly predicted that Prince Harry would arrive at Balmoral ‘in a Range Rover or something of that kind’, or when Jane Hill, looking out over Buckingham Palace, observed: ‘It is the symbol of the royal family, isn’t it, in this country?’ Yet for the most part Edwards, Hill and the rest did a fine job of guiding the nation through the disorientating moment when our figurehead was lost.

All the same, it was a bracing delight to switch over to GB News and watch David Starkey – black tie, black pocket square with white polka dots, thick black-rimmed spectacles – pontificating at the speed of a royal racehorse. ‘It’s what Walter Bagehot, you know, in the great account of the British constitution, says: republics are boring. Unless of course Donald Trump is president’ – a tongue-flickering chuckle – ‘and then they’re interesting in the wrong sort of way. Whereas in monarchy, the… the abstractbecomes personal, it becomes real, it becomes graspable.’ Why is the King proclaimed at St James’s Palace, Professor? And he’s off again. ‘Whitehall burns out in the 1690s in a vast fire,’ Starkey told us with such relish that he sounded as though he had personally set it alight.

The Proclamation itself, on the Saturday morning, has never been filmed before. I can scarcely remember a more gripping hour of television. First the sheer gossip value of the members of the Accession Council crammed into the picture gallery at St James’s. There, beneath the chandeliers, was the six-foot-two Jacob Rees-Mogg, bobbing over the heads of the judiciary; there, unmistakable even from behind, was Rowan Williams in his purple cassock; there were Keir Starmer and Gordon Brown in serious converse, arms heavily crossed while Tony Blair stood in between. And what could the chief whip and Angela Rayner be discussing so animatedly? And was that Facebook’s Nick Clegg? – well, it must be.

Silence fell, and for those of us who are not constitutional experts an apparently motley crew of bishops, politicians, Prince William and a man in full dress military uniform processed into the room. Penny Mordaunt, last seen drifting in and then out of contention for the Tory leadership, turned out to be an unimprovable Lord President of the Privy Council. ‘My Lords, it is my sad duty to inform you…’ As Mordaunt went on, her cadences moved back through the ages. ‘…shall wait on the King, and inform him the Council is assembled…’

From Shakespeare to Cranmer, as the Clerk of the Council read out the Proclamation. ‘Whereas it has pleased Almighty God to call to himself…’ Directions were given for the Constable of His Majesty’s Tower of London to organise some celebratory gunfire. ‘God save the King!’ everyone shouted, and David Cameron glowed like a schoolboy. Thus they waited for their Sovereign, elevated by words so much finer than all the parliamentary speeches, borne along on a current of tradition so much grander than anything they could have invented; the brilliant and the mediocre, the famous and the unknown, touched and transformed by a power that compressed centuries of history into a moment. It was so much better than talking, wasn’t it?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in