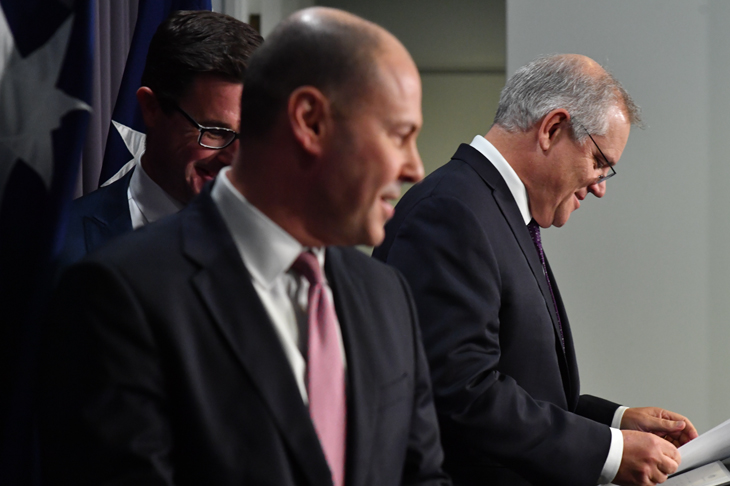

Although in office for a little more than 100 days, Treasurer Jim Chalmers has already been criticised in some quarters for laying blame for Australia’s economic troubles at the feet of the former Coalition government. He is not entirely wrong to do so.

The period the Coalition was in office, even allowing for pandemic-related spending, could hardly be characterised as the golden years of fiscal restraint.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

Daniel Wild is Deputy Executive Director at the Institute of Public Affairs

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in