Love him or loathe him, Lucian Freud was a maverick genius whose life from the off was as singular as his paintings were celebrated. He never really knew his famous grandfather, who left Vienna in 1938 only a year before his death, and one can only speculate what Sigmund would have made of his wayward and wildly gifted grandson on the strength of this effervescent collection of early correspondence.

He certainly would have admired it on aesthetic grounds: a handsome quarto volume, cloth-bound and embossed, whose contents are a model of intelligent design. Every one of the missives – letters, postcards, scraps of paper – is reproduced in facsimile, with accompanying transcription, the reason being that a great many of them include droll and quirky sketches, rendering them artworks in themselves. Freud’s handwriting hardly advances beyond the level of an average eight-year-old (he was a natural left-hander forced to write with his right). He never mastered joined up writing and his spelling and syntax remained comic-atrocious, ‘delishious’ being a favourite term of praise.

These quirky communications are set, like rhinestones on a velvet cloak, within an elegant rolling narrative that explains, elucidates and connects them, propelling the story on through three eventful decades and culminating in Freud’s inclusion in the Venice Biennale of 1954 and his emergence, at 31, as an artist of international renown. We are thereby spared the clunky scaffolding of footnotes (though the text is fully sourced), and we’re in for a roller-coaster ride.

A few colourful childhood notes in invented scripts set the tone, for fantasy, invention and elaboration were key to Freud’s communications. The pace picks up in 1939 when he enrols as an art student at Cedric Morris and Arthur Lett-Haines’s East Anglia School of Painting and Drawing, and branches out into Bohemia, his natural habitat, from where he would fire a volley of droll and wittily illustrated letters to the likes of Stephen Spender, who described him as ‘totally alive, like something not entirely human, a leprechaun, a changeling child’. Breathless, flirting, teasing letters went out daily to a posse of girlfriends, or would-be amours, full of wild anecdotes, in-jokes and cartoons.

He also kept up a running commentary throughout the 1940s with the painter John Craxton, with whom he shared a studio and many travels. He is at his zaniest in these letters to ‘Spag’ or ‘Craggs’, who later observed: ‘I think he couldn’t help being a bit surreal; if surrealism was the unexpected, the thing taken out of context, then Lucian by his own nature was surreal.’ The two shared a private language known as Eggy-Peggy and much else, as they buccaneered through the high life and low life of Europe.

Love affairs and a first marriage soared and crashed, law suits threatened and debts accumulated. Freud’s career progressed in fits and starts but never fast enough to fund the gambling, and his letters to various patrons are among his most self-aware. Admonished for his spendthrift ways, he admits that ‘the wolves and their needs are created entirely by my tastes and feelings, but it is through my tastes and feelings that I live as a painter and as a person’.

On he went carousing, reporting back to Ann Fleming on a high-society fancy dress ball in Biarritz. She was among his favourite correspondents, though predictably he loathed her new husband Ian: ‘He wasn’t nasty, he was ghastly, he didn’t have friends, he had golfing friends.’ The volume ends with Freud’s second marriage, to Caroline Blackwood, and the many skirmishes over his inclusion in the Venice Biennale, his ratcheting anxiety and irritation about what to include/exclude almost burning off the page.

How much this volume adds to the several biographies already written depends on how primary you like your sources to be. The raw spontaneity and energy of each illustrated page conveys Freud’s moods and preoccupations in a way that no biographer can match. Yet the narrative is necessarily patchy, following those letters that survive, thanks to the vagaries of fortune, where others have perished or disappeared.

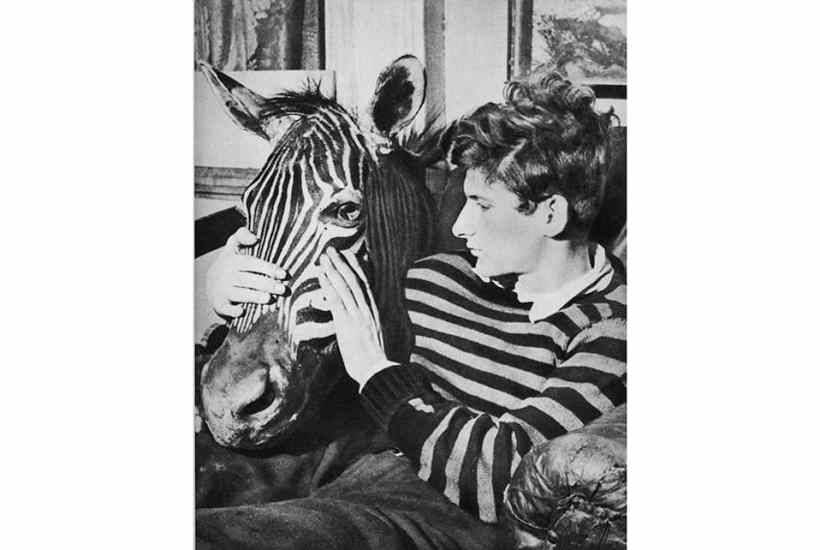

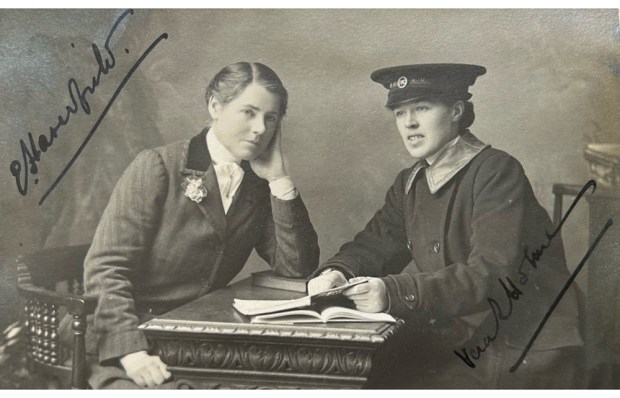

But the calm clarity of the commentary spins it all together, and many of the letters included here have never been seen before. In editing this volume, Martin Gayford (a friend, and the subject of ‘Man with a Blue Scarf’) and Freud’s longtime assistant David Dawson never intrude. Yet their closeness to the painter, allied with keen research, throw light on frequent obscurity, and they complement Freud’s words and artworks with rarely seen photographs. Altogether, this is as vivid a Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man as we shall ever have, and compelling reading for Freud aficionados and amateur psychologists alike.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in