In this week of mourning, much of the news which would normally get covered has sunk without trace. Even so, this morning’s news of a drop in unemployment has managed to catch the eye. The unemployment rate has fallen by 0.2 to 3.6 per cent – below where it was at the beginning of the pandemic and at its lowest level for 48 years. This, at a time when economic growth is more of less static and the bank of England is warning us to expect a severe recession next year, is extraordinary.

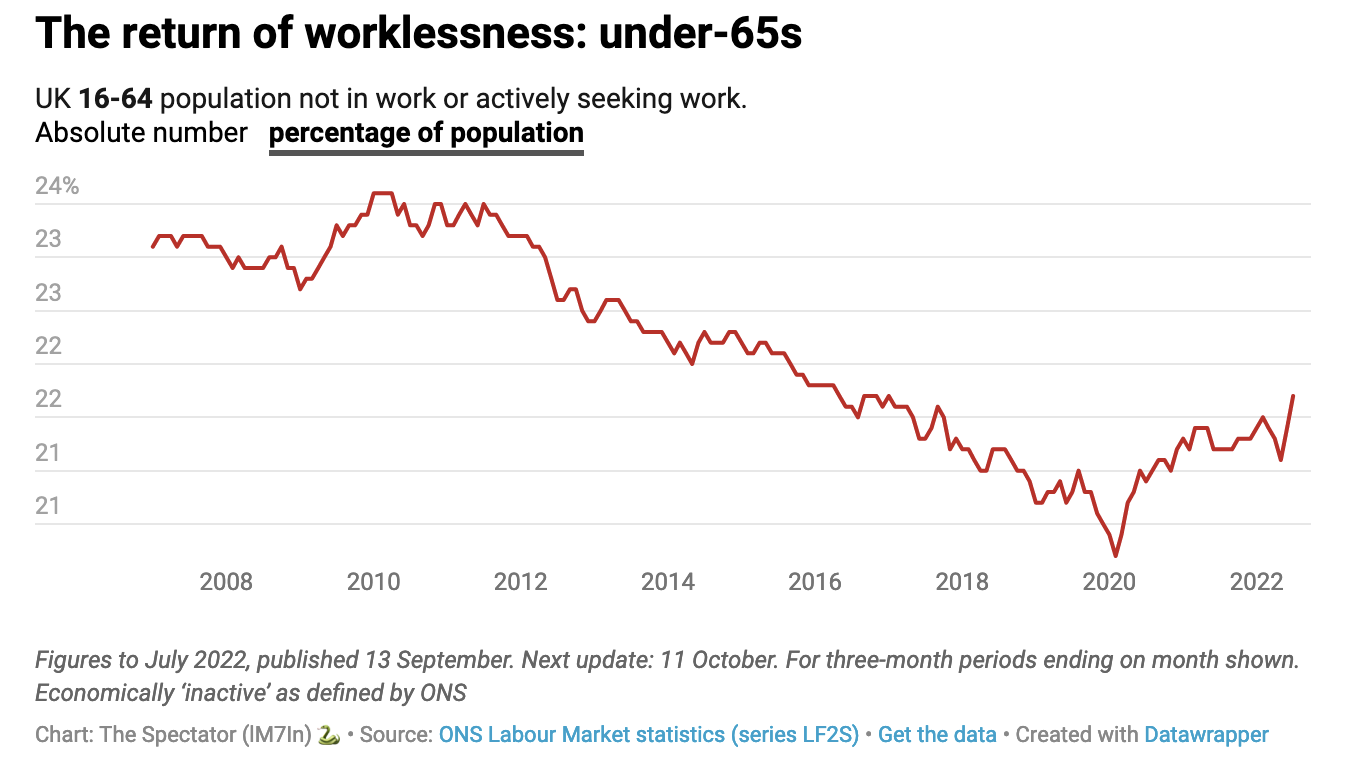

I only wish that the official unemployment figure could be trusted. But there is another stark figure to come out of this morning’s release by the Office of National Statistics (ONS): that the rate of economic inactivity (people aged between 16 and 64 who are not working) has grown by 246,000 over the course of the past 12 months.

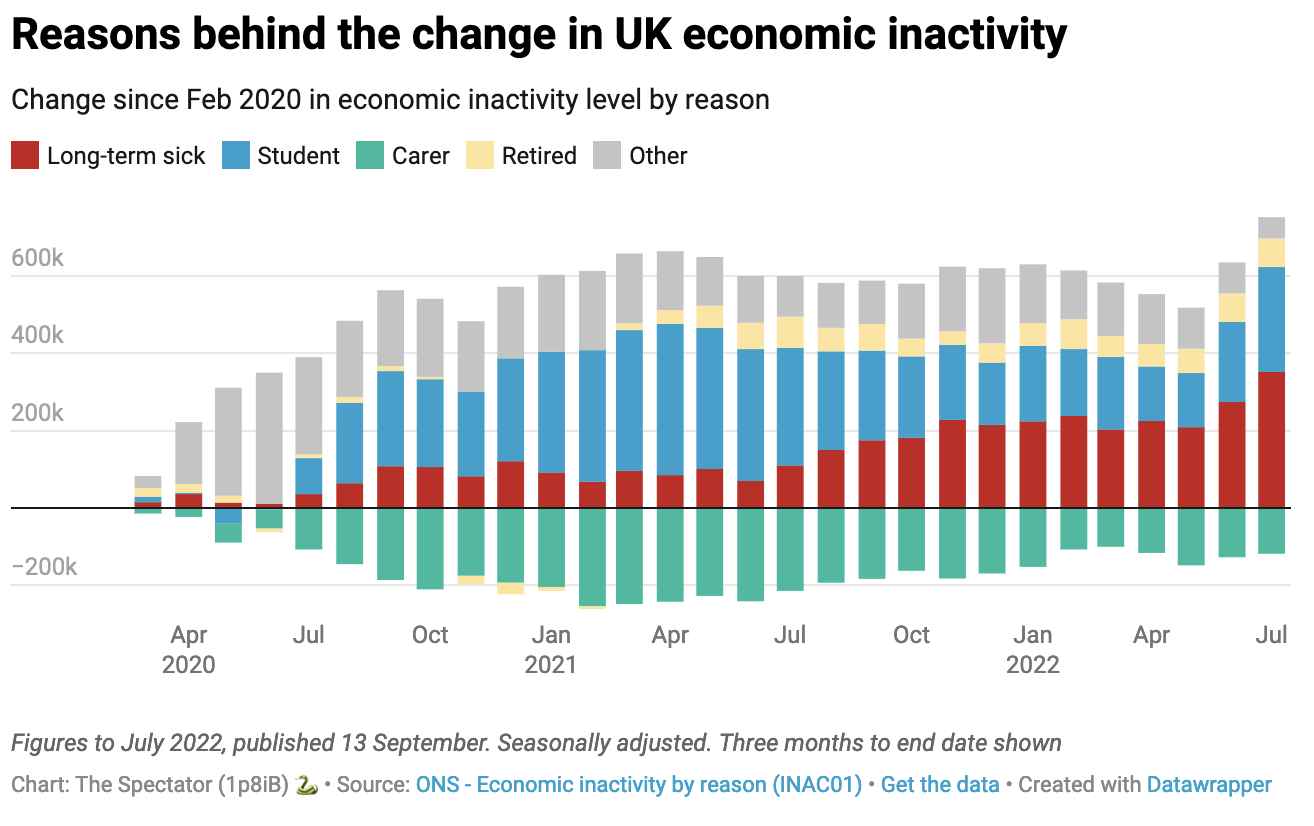

While the figure for economic inactivity includes full-time students – and the number of these has grown – further examination shows that the principal reason for the rise is an extraordinary surge in the number of people claiming long-term sickness benefits. Between May and July 2022 the number of people recorded as economically inactive was 641,710 higher than between December 2019 and February 2020. Of this rise, 270,836 was down to an increase in the number of students and 352,011 was down to an increase in the numbers of long-term sick.

Is this the result of long Covid, or is it a return to the bad old days when governments used to massage unemployment figures by shunting as many people ‘onto the sick’? Today’s ONS release, sadly, can’t tell us this. But there has been a remarkable turnaround since the pandemic.

Universal Credit was specifically designed in part of tackle the problem of long-term sickness benefit. For years, people had been put on these benefits without anyone ever asking them whether they had returned to fitness or helping them back into employment. It helped reduce the unofficial unemployment figure but at the cost of keeping people unnecessarily out of work. Universal Credit sought to reverse this by obliging those on sickness benefits to prove that they were still unable to work. And for a decade it seemed to work. The economic inactivity rate fell consistently from the end of the 2008-09 recession until the beginning of 2020. Since then, however, it has started to rise again, to the point at which it is beginning to undermine the otherwise good news on employment.

There is a lot that is genuine about Britain’s low unemployment rate. A flexible labour market has made it much easier to create jobs than it is in countries which make it far harder to hire and fire staff. France’s unemployment rate, for example, is 7.4 per cent. Much as the Labour party likes to go on about zero hour contracts and job insecurity, the reality is that if we had a labour market like that of France many of the people working in insecure jobs wouldn’t have a job at all. But Britain’s employment miracle is going to look a lot less of a miracle if everyone can see that the unemployed are being redesignated as being too sick to work.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in