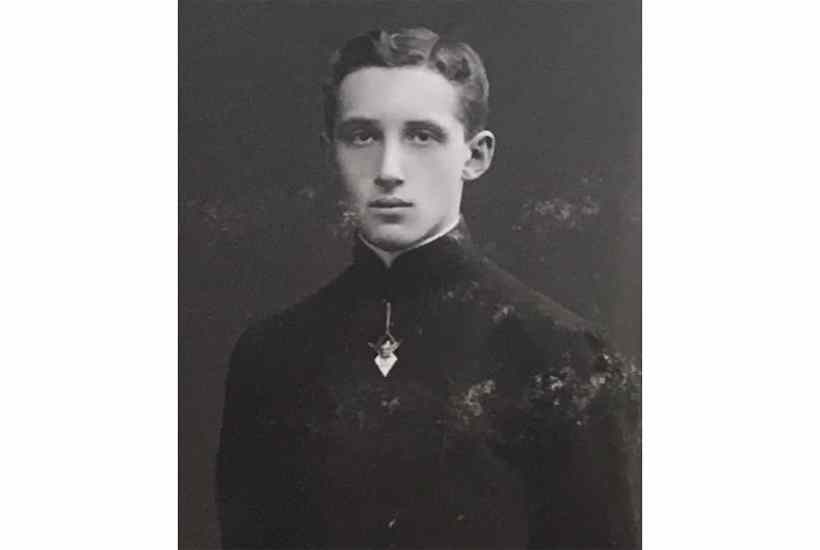

Yuri Felsen, born in St Petersburg, was an exile in Riga, Berlin and Paris and died at Auschwitz in 1943. Had his archive not been destroyed, we might find him on the same shelf as Vladimir Nabokov, Vladislav Khodasevich and Ivan Bunin – the glittering Russian literati of 1930s Paris – and Georgy Adamovich, who said that Felsen’s prose ‘left behind a light for which there is no name’. With this new translation of the 1930 novel Deceit, that light has been brought back from dim obscurity.

In this first of three novels Felsen published, we follow the unnamed narrator’s tortured obsession with the ‘unequivocally irresistible’ Lyolya Heard, who drifts in and out of his life in Paris, leaving him in an intoxicating loop of ecstasy and despair. The prose is electrifying, irascible and melodic, a potentially unruly mixture brought harmoniously together by the translator Bryan Karetnyk.

To contain these digressions, Deceit takes the form of a diary, situating itself alongside Gogol’s Diary of a Madman, Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground and Nabokov’s Despair, all of which comprise similarly frenzied monologues by protagonists who could be madmen, geniuses or both. As the narrator pushes outwards, the diary form pulls in. When the psychoanalyst Lou Andreas-Salomé described Friedrich Nietszche’s stare as ‘inward, as if into a distance’, she could easily have been tracing the complex psychological dimensions of Felsen’s prose.

Our narrator suffers from neurasthenia, which manifests itself in his obsession with Lyolya, but is perhaps rooted in his loss of homeland and the maddening, monotonous trauma of exile. Deceit is forever descending into what the narrator calls a ‘mad onslaught of thoughts and events’, but this fate is avoided by recriminating interjections (‘miserable distraction’, ‘useless endeavour’) about his own literary project. In repeatedly calling out this failure of expression, Felsen achieves that compelling paradox of saying something while never really saying what that thing is.

Called the ‘Russian Proust’, Felsen is often described as a purveyor of auto-fiction before it existed. But if the genre today implies self-understanding through the edifying process of writing, Felsen offers a more sobering conclusion: that writing may in fact bring us both closer to and further from reality, from the blinding light of truth. It is about this recursive behavioural tendency – to fly towards and away from illusion and fantasy – that Felsen writes: as if to say, deceit is both poison and remedy, a most unbearable and entirely necessary human contradiction.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in