On 15 June 1645, as Thomas Fairfax’s soldiers picked over the scattered debris on the Naseby battlefield, they made a sensational discovery. Amid the corpses and musket balls, dismembered limbs and severed swords there nestled a carrying case of personal letters and papers. It was nothing less than the king’s private correspondence. The cache included letters between Charles I and his queen, Henrietta Maria – his always opened ‘My deare harte’ – which discussed in detail the tactics and strategies of the war. Never ones to miss a PR opportunity, the Parliamentary high command ordered that a selection should be published with a guiding commentary. The first editorial note got straight to the point:

It is plain, here, first, that the Kings Counsels are wholly governed by the Queen… Though she be of the weaker sex, borne an alien, bred up in a contrary religion, yet nothing great or small is transacted without her privity and consent.

It was the start of a powerful narrative that cast the French-born queen as the king’s evil adviser.

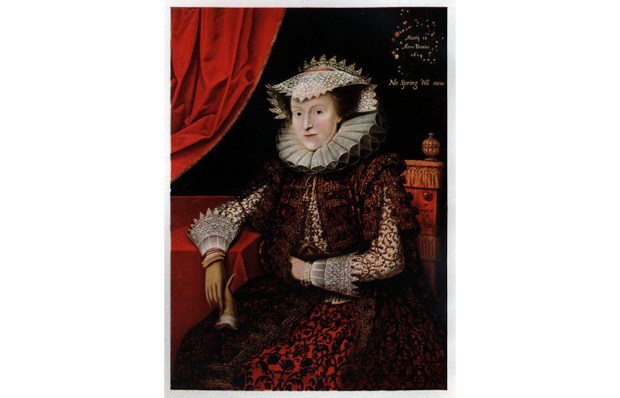

That she might ever be characterised as a Stuart-era Lady Macbeth would have amazed the bevy of courtiers and hangers-on who had accompanied Henrietta Maria to England on her arrival as the wife of the English king 20 years earlier. Childlike in physique and just 15, she was mignon and looked, according to Leanda Lisle’s sympathetic biography, ‘like a 17th-century Audrey Hepburn’.

Naive and spoilt she might have been, but her lineage was mighty, her names those of her formidable parents, Henri IV of France – the erstwhile Henri of Navarre who had abandoned his Protestant faith to bag the crown of France – and Marie de Medici, the imperious daughter of the Grand Duke of Tuscany. Both had lived through the turmoil of religious war in the aftermath of the schism of the Reformation. That there was trouble ahead for their daughter should have been obvious when, in the proxy marriage ceremony, the Protestant groom’s representative couldn’t even enter Notre-Dame de Paris where it took place.

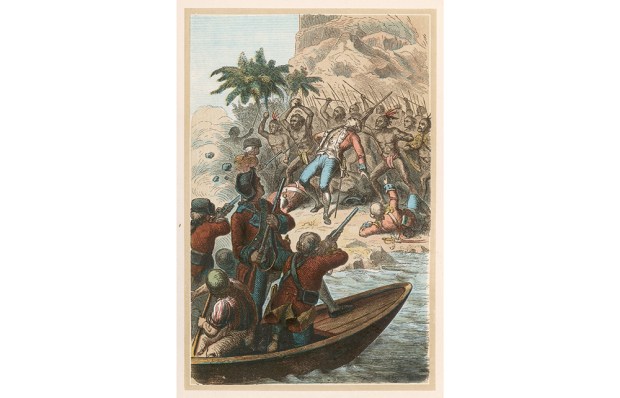

Arriving in England, Henrietta Maria found herself out in the cold. Her shy and awkward husband was in deep thrall to the charismatic and controlling Duke of Buckingham, and set out on a series of half-baked military interventions in Europe that each ended in disaster. Tears and tantrums followed. The misery would be abated by an obscure assassin, who thrust a blade into the duke’s torso in a pub in Portsmouth, thereby creating a vacancy for a royal favourite – into which Henrietta Maria neatly stepped.

With the role, as everyone from Piers Gaveston to Anne Boleyn had found, came unpopularity. But she was largely oblivious to it, and the 1630s would be a time of happiness and harmony for the royal couple. Charles had decided to do without parliament, and he and his wife occupied themselves buying paintings by Rubens and Van Dyck, dancing at court masques designed by Inigo Jones and Ben Jonson, and producing children with joyful regularity.

The fun could not last. Charles I’s terrible political judgment was a character flaw that had developed long before he became close to his wife. But in his love for her he allowed her Catholic chapels at St James’s Palace and Somerset House to become ever more visible and vibrant – dangerous in an rabidly anti-Catholic country nursing a grudge against its king.

When the British Isles dissolved into civil war, Henrietta Maria came into her own. She had cut her teeth on the Anglo-French court intrigues of the era of Cardinal Richelieu, with which Alexandre Dumas would have fun two centuries later. But the existential crisis of the war brought out in her a new seriousness and strength of character. She travelled to the continent to raise funds, narrowly avoided capture and injury on numerous occasions and acted with courage and intelligence throughout.

Indeed, the revolutionary years were an epoch of formidable females, the cast of other viragos including Lady Brilliana Harley, Charlotte, Countess of Derby, Anne Fairfax and Anne Monck. After her husband’s execution, the exiled Henrietta Maria, back in her native Paris, became bitter, and her capacity for compromise withered. Her brutal rejection of her youngest son when he upheld his father’s dying instruction to remain faithful to the Protestant faith is a hard task for even the most approving biographer to excuse.

Henrietta Maria’s remarkable life is recounted with gusto in this sharp, sparky book. While it does not claim to cut new historical turf, it makes vivid use of recent work on her court and queenship, brings people and personalities to the fore and will be a particular delight to those new to the period. Few consorts of any age so vividly exposed the old lie that women were ‘the weaker sex’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in