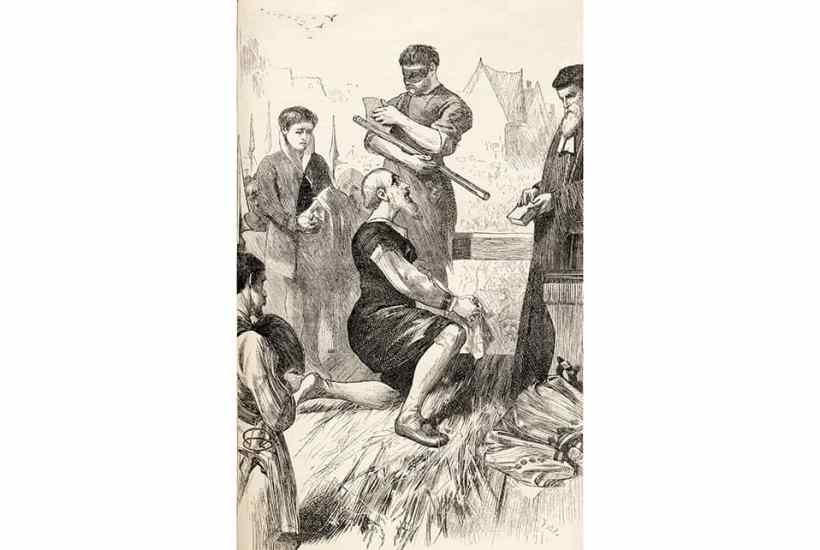

As Tory writers reflected on the safe passage of the Stuart dynasty through the Exclusion Crisis of 1679-81, an anonymous author urged contemporaries to learn the lessons of English history. The Rebels Doom (1684) offered some thumbnail sketches of various unsuccessful rebellions and attempted revolutions that had threatened the monarchy since the reign of Edward the Confessor, in order to show ‘the Fatal Consequences that have always attended … Disloyal Violations of Allegiance’.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in