Spectator Australia contributor, James Allan, recently made a couple of very important observations about the Liberal Party.

First, he showed conclusively why Simon Birmingham was wrong to blame recent blamed electoral losses on the party’s move to the Right. Allen was also correct when he concluded that, ‘I think the vast majority of Australians agree with Katherine Deves.’

His comparison with Margaret Thatcher, however, was not correct. Her ruthless style was facilitated by the UK’s unitary constitution. The Australian Constitution was a federal model to prevent centralisation of political power in the Commonwealth. That most political power now resides in Canberra is due to the High Court’s acceptance of Menzies’ submissions.

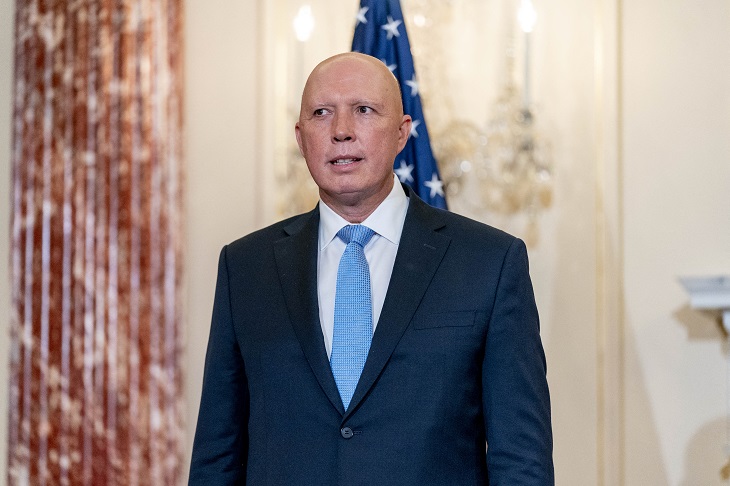

When Menzies articulated his political principles in 1942, he appealed to a select middle class. The heart of the disagreement between people like Opposition Leader Peter Dutton and Leader of the Nationals Simon Birmingham, or even New South Wales Premier Dominic Perrottet and his Treasurer Matt Kean, is whether those political principles are amenable to progress. How that argument concludes will tell us whether the Liberal Party is conservative or progressive.

It is ironic that an election that cost the Liberal Party so dearly should occur on the eve of the anniversary of Menzies’ famous forgotten people speech eighty years previously. Do Menzies’ political principles have any relevance to the debate that currently threatens the Liberal Party? The speech, in part, is Menzies’ apology to his Scottish heritage, combining his admiration for Scottish farmers and their families with a Calvinist defence of individual initiative.

The speech, described by his devotees as defining the shape of post-war Australia, is more partisan than inclusive. While Menzies appeals to a middle class, he excludes a large portion of the nation who he implies have communist sympathies.

In a personal touch, he identifies his ‘middle class’ as forgotten people, ‘The kind of people I myself represent in Parliament – salary-earners, shopkeepers, skilled artisans, professional men and women, farmers and so on. These are, in the political and economic sense, the middle class.’ He calls them the bourgeoisie whom ‘the communist has always hated’.

He divides Australians into economic classes and excludes from his middle class both the rich and ‘the mass of unskilled people, almost invariably well organised, and with their wages and conditions safeguarded by popular law. What I am excluding them from is my definition of the middle class’.

Despite the exclusions, he defines his middle class much more broadly as all those with a ‘stake in the country’, consisting of those: ‘Found in the homes of people who are nameless and unadvertised, and who, whatever their individual religious conviction or dogma, see in their children their greatest contribution to the immortality of their race.’

While Menzies middle class was just the traditional family, only the bourgeoisie are the backbone of the country, since he has also excluded the rich, as: ‘They have as a rule shown neither comprehension nor competence. But I exclude them because, in most material difficulties, the rich can look after themselves.’

Paradoxically, despite Menzies’ express statement, the wealthy he excluded became both shaft and tip of the Liberal spear. Menzies insight into the rich, however, is actually an insight into the problems that Sydney eastern suburbs and similar electorates around the country posed for the Liberal Party on May 21 this year.

Those electorates are no longer exclusive to ‘those who control great funds and enterprises’. Economic progress has added new members to the wealthy elites in those electorates. Insulated by wealth from life’s misfortunes and imbued with different principles from Menzies’ supporters, they are immune from the virtues of the family. They seek instead to protect their habitat from the evils of economic growth for which the Liberal Party stands.

In the United States, Donald Trump was the first to identify the changing fortunes of the Republican Party which once represented large financial corporations and a wealthy elite. Democrats used to stand for trade unions and working men and women. Trump was the first to observe that Wall Street, the giant corporations and the wealthy elite, had changed sides.

His electoral success in 2016 proved this with policies that appealed to America’s urban families, something some Republicans still resist. His resonance with American families was a long-term threat that drove Democrat lies and electoral fraud.

If the Liberal Party is to return from its latest defeat, it must present as a defender of the urban family against media voices that deny its natural basis and over the cacophony of climate sophistry masquerading as science. Menzies accurately defined that class by reference to their homes and their children at a time when there was general agreement about what the family looked like.

As the source of Australia’s future, the family is the most important Australian asset. Selfish people who seek to change the family to suit their idiosyncratic view of human nature will change the nation’s future. Marx and Lenin fully understood this and their rejection of human nature accounts for the chaos that resulted.

Though the threat of communism has passed, its equally dangerous mutations of gender and sexuality liberation or Black Lives Matter and minority oppression narratives all reject human nature in the name of human history and progress and the family as the cornerstone of liberal democracy.

Conserving the family means nothing less than conserving human nature and Katherine Deves should be congratulated for her courage in doing so.

While Peter Dutton has declared that he wants to be kinder and gentler, perhaps to contrast with the ALP mean girls of which there are many even among the men, he needs to understand that human nature is not fence that one can straddle. ‘Kinder and gentler’ is how one deals with children, but with adults it is not an alternative to what is naturally just. The discipline that family life imposes on men and women is only possible if there is competition from other relationships.

The Liberal Party must decide if it wants a future Australia to be progressive or conservative.

If conservative, it must do more than boast of its economic credentials, as important as these are. It will need to demonstrate to Australian families that it can protect them from influences that not only challenge family life, but threaten its existence.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in