What does home mean? Where your dead are buried, as Zulus believe? Or where you left your heart, as a migrant’s saying goes? In these pages William Atkins melds history, biography and travel into a meditation on exile and the meaning of home. It is a volume for our times, as the author seeks to reveal ‘something about the nature of displacement itself’.

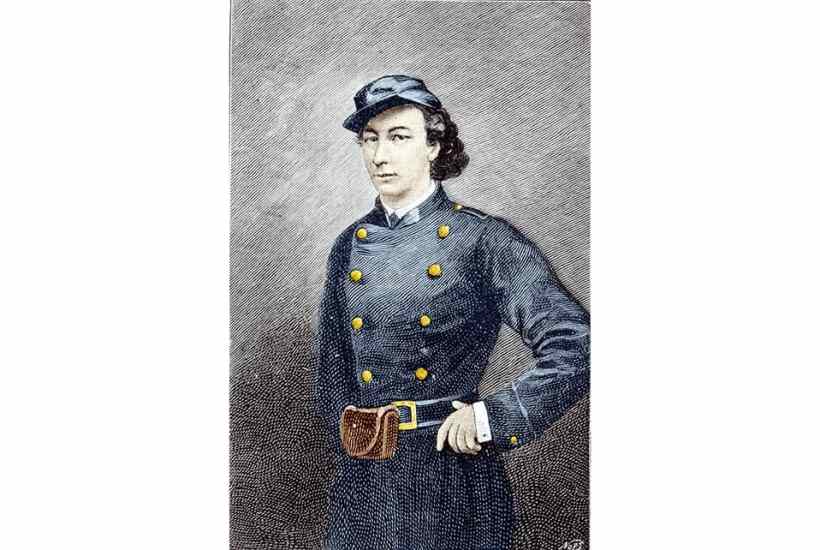

Part One introduces the three 19th-century political exiles who form the spine of the book. Louise Michel (1830-1905), the illegitimate daughter of a maid in Haute-Marne, became an anarchist and Communard, who murdered policemen with her Remington carbine. Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo (1868-1913), the young king of the Zulu nation, took up arms to resist southern Africa’s colonial overlords. The Ukrainian-born socialist revolutionary Lev Shternberg (1861-1927) committed himself to the overthrow of tsarism. All three were packed off to remote islands, each a banished exile similar to a Roman relegatio like Ovid, whom Atkins invokes.

In Part Two, the author, whose previous books include The Immeasurable World, an account of seven desert journeys, fills out the three periods of exile and follows in the footsteps of his rebels. In the French colony of New Caledonia in the South Pacific, 17,000 miles from Paris, Michel studied papaya jaundice and tried to farm silkworms. Dinuzulu departed for the British dependency of St Helena in the South Atlantic, 2,500 miles from home, travelling on a mail ship (as I did: in my case the last one, in 2016). There he and his 13-strong retinue hosted a party for Queen Victoria’s birthday. The St Helena Guardian praised Dinuzulu’s dignity. He wrote home: ‘I am like the fly wrapped round in the spider’s web, though its heart is yet alive.’

Sakhalin Island in the Russian Far East, ‘a byword for bleakness and isolation’, lies 28 miles north of Japan in the Sea of Okhotsk. Shternberg went there, 11,000 miles from home. He devoted himself to ethnography and produced a study of the Nivkhi people, known to Chekhov as Gilyak: Anton Pavlovich made Sakhalin famous when he published a book on the penal colony in 1893 (he overlapped with Shternberg, but the pair never met).

Atkins is a character in the story rather than an agent of the material: in effect he becomes the book’s fourth protagonist, weaving his experiences with those of his subjects, making links between him and them (‘during their sea voyages they are freed to occupy a common realm outside space and time’). He is an amiable companion, deploying an engaging conversational tone (‘I have the feeling… ’) and positioning himself as far as he can from the I’ve-Got-a-Big-One tribe of white chumps in remote lands. At a party ‘in the absolute shade characteristic of banyans’ in New Caledonia, he hears a Kanak telling his neighbour: ‘If he [Atkins] doesn’t dance I’ll kill him.’

It is hard to jemmy travelogue into historical material. Even though the author labours at his links with determination and intelligence, the transitions don’t always work. The effort slows the narrative. But Atkins hears echoes of the past in the present – as the rest of us could all the time if we listened.

Michel emerges as the fullest character, because she left more primary material, notably a published memoir. Atkins marshals that and all his sources adroitly. He is an able writer, picking the fertile fact from the heap of negligible things. Michel’s friend Victor Hugo said he had to eat rat pâté during the Commune; Atkins has ‘latex sausage’ on the overnight ferry from Vanino to Sakhalin.

Part Three covers the post-exile periods. A crowd of 20,000 met the 50-year-old Michel and her five cats at Saint-Lazare seven years after she had sailed away. (Streets and schools carry her name today.) She continued living a public life as a radical activist, often from a prison cell. When the 38-year-old Dinuzulu steamed back to Africa after seven years on St Helena, his entourage swollen by progeny and five donkeys, a boundary commission had divided his kingdom into dozens of petty chiefdoms. Home was no longer home, and things went badly for him. As for Shternberg, away for eight years, Engels’s proto-ethnography had influenced him, and when the German read his Sakhalin field reports, he rejoiced that they supported the Marxist theory of social evolution. Shternberg’s Social Organisation of the Gilyak People came out in 1905.

Atkins says he was drawn to his subjects because ‘their lives were shaped by three winds that blow strongly today – nationalism, autocracy and imperialism’. He wrote memorably in The Immeasurable World about the migrant crisis, in that case the Mexican tragedy in Arizona. This new book ends with the assertion that his own nostalgia, evoked by the voyages described, is for ‘a country that no longer exists’ – his own, the sceptred one that for so long welcomed strangers and exiles: the safe harbour.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in