One thing that Covid lockdown made us appreciate was the importance of being outdoors. When we were finally allowed into them, national and local parks became chockfull and many people rediscovered that being in the open had health benefits.

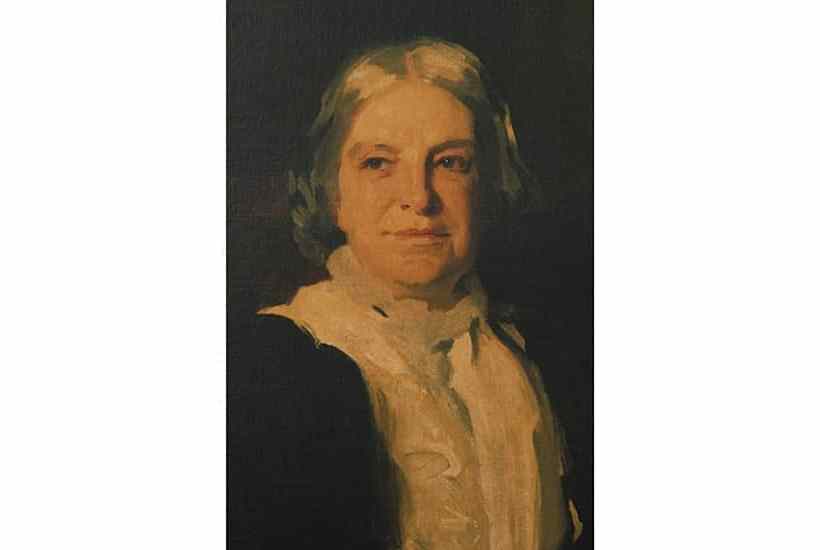

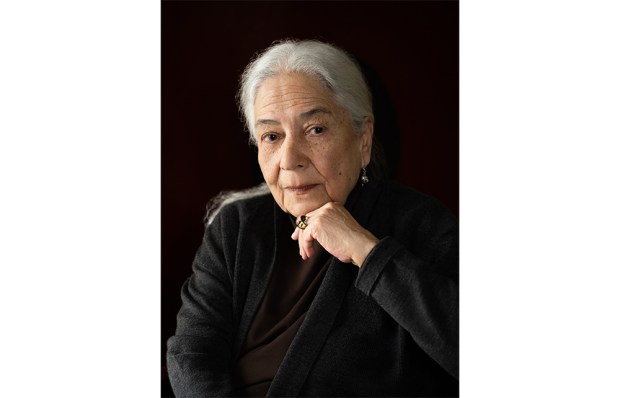

How timely, then, that Matthew Kelly has written an account of four redoubtable rural activists: Octavia Hill, Beatrix Potter, Sylvia Sayer and Pauline Dower.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in