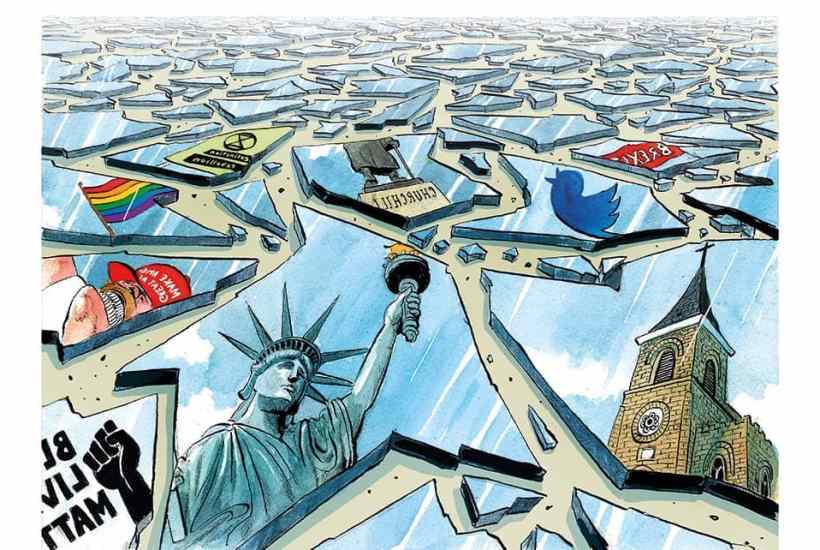

There are many ways to fracture a people. But one of the best is to destroy all the remaining ties that bind them. To persuade them that to the extent they have anything of their own, it is not very special, and in the final analysis, hardly worth preserving. This is a process that has gone on across the western world for over a generation: a remorseless, daily assault on everything that most of us were brought up to believe was good about ourselves.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

Douglas Murray’s The War on the West is out now.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in