In the week before Orthodox Lent began, some 233 RussianOrthodox priests published a petition calling for peace. The signatories spokeof the ‘fratricidal war in Ukraine’, with a call for an immediate ceasefire,and deplored ‘the trial that our brothers and sisters in Ukraine wereundeservedly subjected to’. Anyone who knows how authority is exercised in theRussian Orthodox church, and how closely it has allied itself with Putin’sauthoritarian state, will recognise the clerics’ courage. But what effect is itlikely to have on the attitude of the highest authorities in the church?

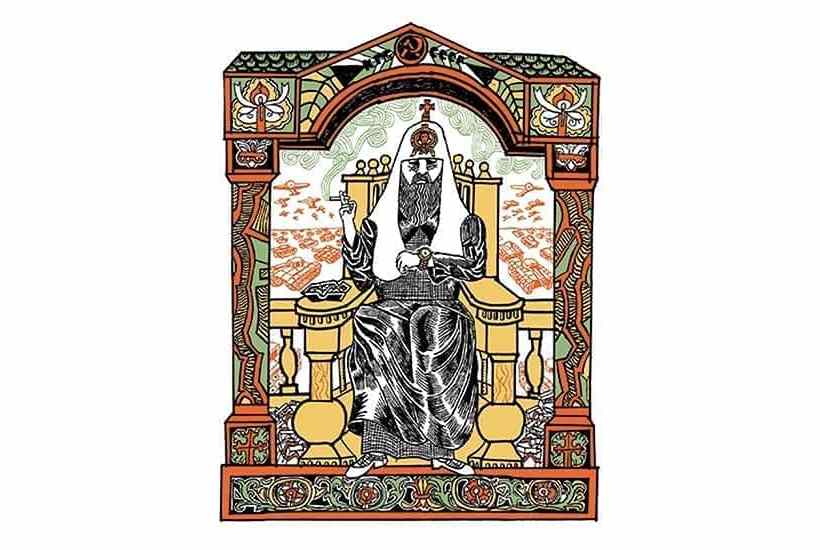

To answer these questions, we need tounderstand not only the centuries-old link between political power andreligious authority in Russia, but also the record of the key players. Onemajor figure is Kirill I, Patriarch of Moscow and all Russia. He is anenthusiastic supporter of Putin’s and has not relented in his praise for thewar. In his sermon on Forgiveness Sunday, he described Russia’s ‘militaryoperation’ as justified and almost sacred. Repeating accusations of genocidal behaviourtowards the breakaway Russian entities in the east, he complained thatUkrainians were waging a more sinister war at the meta-physical level, againstRussia and against Christianity, by backing immoral causes like gay andtransgender rights.

Kirill’s endorsement provides a religiousgloss for the Kremlin’s ideology of a ‘Russkiy Mir’ or Russian world. The termimplies Russia’s destiny is to bring the peoples of the former Tsarist andSoviet empires under its leadership. It looks back to the idea of Moscow as the‘Third Rome’, which saw ‘Holy Russia’ as the protector of the Orthodox peoples.It is perfectly attuned to the nostalgic imperialism promoted by Putin.

The petition of the ‘peace priests’ isunlikely to be more than a minor irritation to Kirill. Its signatoriesconstitute a tiny proportion of the more than 40,000 Russian Orthodox clergyand there are no metropolitans or other influential senior clerics among them.This does not mean that there are not many more priests who oppose the war. Thereare reports from inside Russia of enormous stress on priests reluctant tosupport the Kremlin. Few are willing to risk speaking out. Threats from aboveare mirrored by pressures from below. Outside the big cities, support for thewar is strong among the elderly rural populations who rely exclusively onofficial sources for information, and who often form the backbone of theirflocks.

For the moment, Kirill and Putin may thinkthat they have little to fear from within the church in Russia. The effects ofthe war on their church’s relations with the outside world, however, willconcern them more. Kirill now faces a setback in his campaign to assume themantle of leadership within world Orthodoxy. The Orthodox church has no popeand Moscow seeks to supplant Bartholomew I, the Patriarch of Constantinople,who in theory is first among equals. In 2019, Bartholomew recognised anindependent church in Ukraine. Although this church attracted a growingfollowing, until the invasion the majority of Ukrainian Orthodox, particularlyin the Russian-speaking east, remained loyal to Moscow. That loyalty is nowstrained. Whole dioceses have broken with Moscow, and this trend will likelycontinue. This matters, because the Ukrainian faithful of the Moscowpatriarchate form a large proportion of the estimated 90 million members ofKirill’s church.

Another important contingent is formed bydioceses and parishes outside Russia and Ukraine, prized by the Kremlin as animportant focus of Russian influence. Some, like the long-established Russianparish in Amsterdam, have already seceded. Others are distancing themselves.Most are likely to be experiencing difficulties in maintaining internal unity.Some independent national churches which had been tempted to back Moscowagainst Constantinople appear to be reconsidering.

Another worry is the effect on ecumenicalrelations. Kirill has said that he will never unite with non-Orthodox churches.At the same time, he has cultivated good relations with the Vatican and theWorld Council of Churches, in the belief that it enhanced his influence. In2016, while in Cuba, he became the first Moscow Patriarch to meet a reigningPope, and the two produced a statement which to many (including many Orthodoxopposed to Russian hegemony) seemed astonishingly compliant with Moscow’secclesiastical Russkiy Mir doctrine.

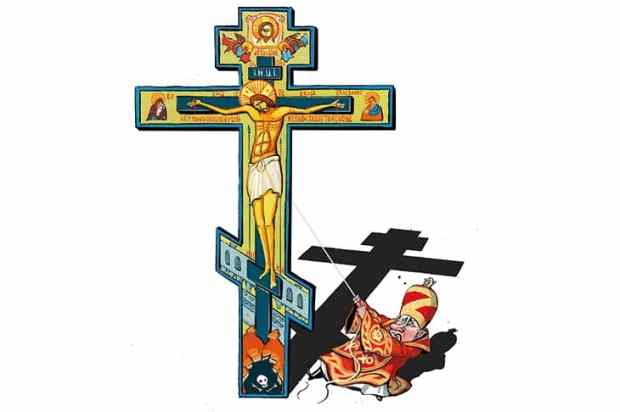

Now Pope Francis has jettisoned the Vatican’straditionally neutral approach to international conflicts by delivering analmost explicit rebuke to Kirill after a video conference, and has sinceclearly pointed the finger at Putin’s aggression. Even Rowan Williams, whosescholarship shows a particularly deep knowledge and love of the Russianreligious tradition, has called for the Russian church to be excluded from theWorld Council of Churches unless its leadership repents.

A key part of the Kremlin’s strategy ofexerting influence through its church has been through the weaponisation ofculture-war rhetoric. Conservative Christians, from traditionalist Catholicsand Orthodox to evangelical Protestants, have seen Kirill and his church asimportant allies in resisting the dominance of western liberal mores. Kirill’sreference to Gay Pride marches in his attack on Ukraine was deliberately aimedat bolstering support from these quarters.

The signs are that this backing is collapsing.There are of course some who prefer to believe the Kremlin’s preposterousversion of events. But many others recognise the brutal authoritarianismlurking behind the mask of piety. The marriage of conservative moral principlewith unscrupulous political expediency has been exposed.

It is impossible to see how secure Putin’sgrip is on power, or what lies in store for the church which he has succeededin instrumentalising as much as any tsar ever did. Kirill may see himself asthe Tsar’s good servant, but God’s first. May God grant him a merciful hearingbefore the dread judgment seat, as the Orthodox liturgy prays. But the judgmentof history may not be so merciful.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Fr. Mark Drew is a priest serving in the Archdiocese of Liverpool.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in