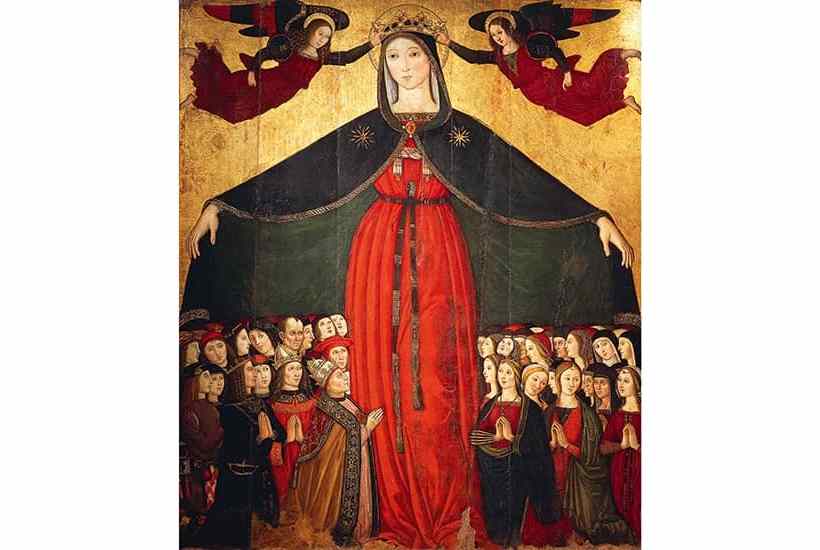

The Catholic church has always venerated Mary (‘Mother of God’) above other saints. But in recent years there has been a slight (a very slight) cooling in the church with regard to the inclusion of Mary in the liturgy of the mass. It’s been an English custom since medieval times to recite a Hail Mary (a verse of the rosary – the traditional Marian prayer) at the end of the ‘Prayers of the Faithful’ – the sequence of introductory prayers in the main body of the service.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in