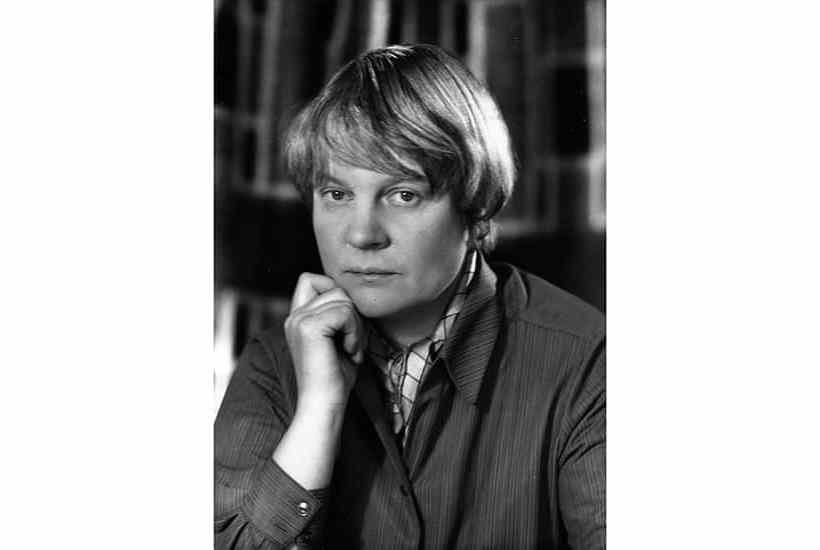

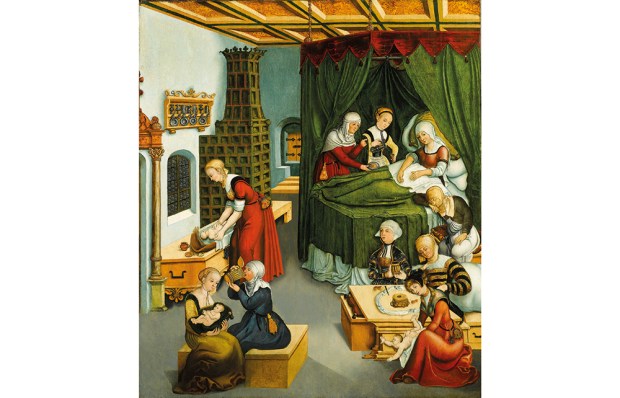

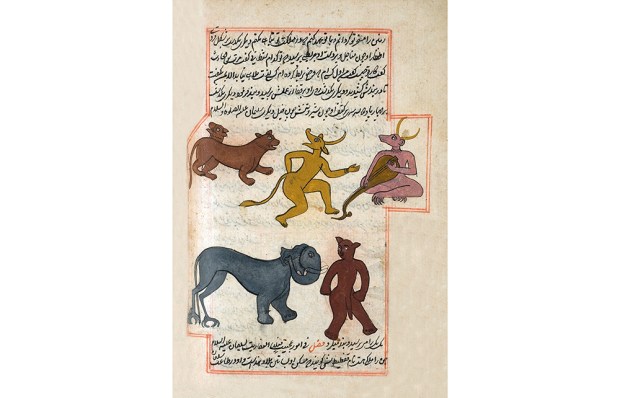

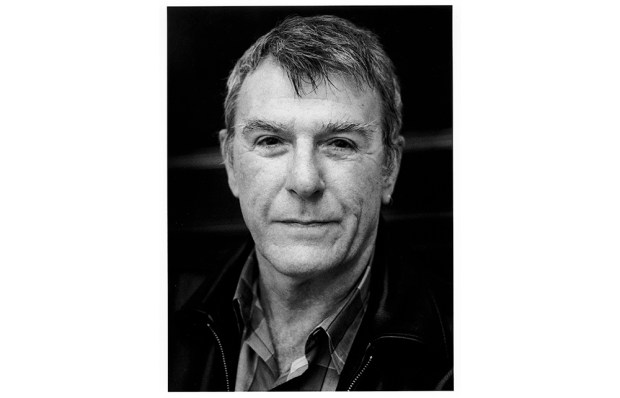

Metaphysical Animals tells of the friendship of four stellar figures in 20th-century philosophy — Mary Midgley, Iris Murdoch, Elizabeth Anscombe and Philippa Foot — who attempted to bring British philosophy ‘back to life’. Fuelled by burning curiosity — not to mention chain-smoking, tea, wine, terrible cooking and many love affairs (sometimes with each other) — they tackled an ancient philosophical question: are humans a kind of animal or not? Dazzled as we are these days by technological possibility, their question only gains in urgency.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in