There’s a scene in Martin Amis’s 1990s revenge comedy The Information in which a book reviewer, who’s crushed by his failures and rendered literally impotent by his best friend’s success, is sitting in a low-lit suburban room beside a girl (not his wife) named Belladonna: ‘She was definitely younger than him. He was a modernist. She was the thing that came next.’

Stuart Jeffries argues in his new book that the thing that came next was in fact a thing that started a couple of decades before Amis wrote The Information. In Jeffries’s telling, postmodernity can be dated to 13 August 1971, when Richard Nixon held a closed-door meeting that led to America’s abandonment of the Bretton Woods policy of gold-backed currencies. ‘Nixon nixed the system,’ he can’t resist writing (and the line isn’t bad).

According to Jeffries, postmodern culture is a diffuse, prolonged effect of this ‘liberation of capital’ in the summer of 1971. The ‘free-floating signifiers’ of literary theory are not a reflection on, but of, the free-floating currencies of the late 20th century. What’s more, he diverges from those who say that postmodernism went down with the Towers in 2001. He believes that we are still living in an era of ‘ghost modernism’. So, by his reckoning, last year marked a half-century of postmodernity.

Postmodernity is in decline, however, and Jeffries’s mood is Spenglerian. ‘What remains is postmodernism’s darker side,’ he concludes. ‘What was civilised has now become barbarism.’ The simplicity of the phrasing is astonishing — though I can’t say I disagree. The question then becomes, why have we become barbarised? Is it merely an effect of trade policies, tax structures and so on? We’ll return to this question.

First, it’s important to note that in his 2016 book, Grand Hotel Abyss, Jeffries showed himself to be a brilliant chronicler of the Frankfurt School (of ‘cultural Marxism’ notoriety). In this new book — whose title is less grand, though no less abyssal — he’s an astute chronicler of several decades of accelerated cultural change.

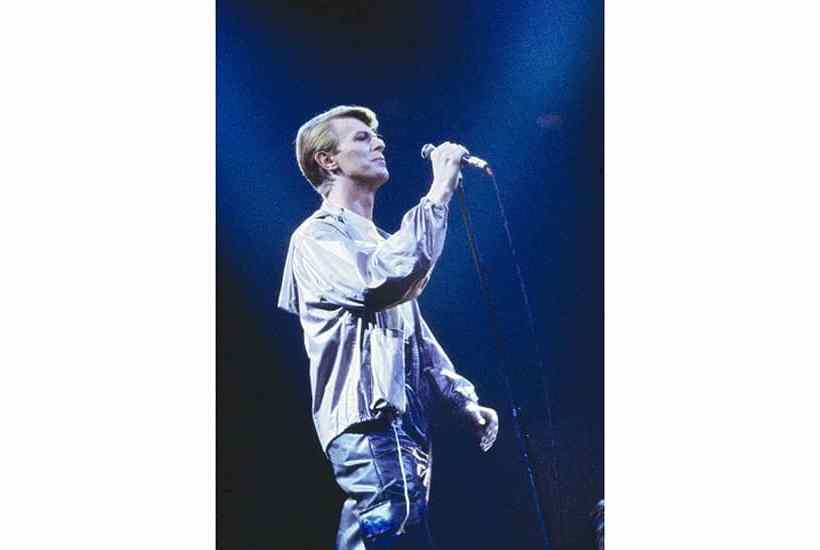

Deracination is a theme. In chapter 2, it’s fascinating to see a Brixton lad — David Bowie — morph into the ‘Thin White Duke’ of late-1970s Berlin. And foreshadowing is everywhere. In chapter 5, Sophie Calle, a voyeuristic performance artist of the early 1980s, is made a harbinger of the ‘surveillance revolution’ that’s still unfolding today. The trouble is that Jeffries takes on too many of Bowie’s and Calle’s contemporaries. Like the title, the book is de trop, and the effect is often boring.

Chapter 7 may be the most uninspiring. It wheels mechanically through Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man and a couple of other end-of-Cold War texts about which endless columns have been printed. Nothing new is said, which is unfortunate, since we have still not grasped what the Cold War’s ending meant.

A deeper objection is that Jeffries’s thesis reduces culture to industry. To him the fall of cultural modernism is triggered by the ‘rise of neoliberalism’. Postmodern culture is merely a ripple effect of the disruptions caused by ‘rentier capitalism’. For left-liberals, the effect of this thesis is soothing. Chic artists and tradition-busting theorists are faulted by Jeffries, to be sure — but only for a failure to see the secret affinities between postmodern practices and theories and much criticised features of neoliberalism, such as ‘deregulation and the computerisation of finance’.

The devils of the piece are politicians whom left-liberals love to hate. Postmodern cultural elites, however, aren’t directly implicated in the rapid, brutal, ongoing dismantling of a tradition — modernism — that Jeffries suggests was ‘neither oppressive nor dehumanising’.

Perhaps because he denies that modernism was oppressive and dehumanising, Jeffries implies that it was all left-modernism. There’s no indication, however brief or subtle, that many of modernism’s most impressive figures were right-modernists. This seems to distort some of his readings. For instance, he notes that T.S. Eliot was ‘working in the foreign transactions department of Lloyds Bank’ when he wrote the ‘Unreal City’ lines of The Waste Land. That’s interesting; but what’s decisive is that the lines in question are a young Eliot’s gloss on a scene in Dante. Where Jeffries sees a reflection of modern banking practices, Eliot sees the foyer to a medieval poet’s hell. There is a difference.

Jeffries blames neoliberalism for a half-century of devastating cultural losses; but our cultural commitments have cultural effects, too. The forms of cultural ‘deregulation’ which accompany hyper-globalisation have their own inner motivations, and their own histories.

‘What was civilised’ may have ‘now become barbarism’ in part because there is a programmatic hostility in the West to the sources of tradition that right-modernists tried — and failed — to shore up.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in