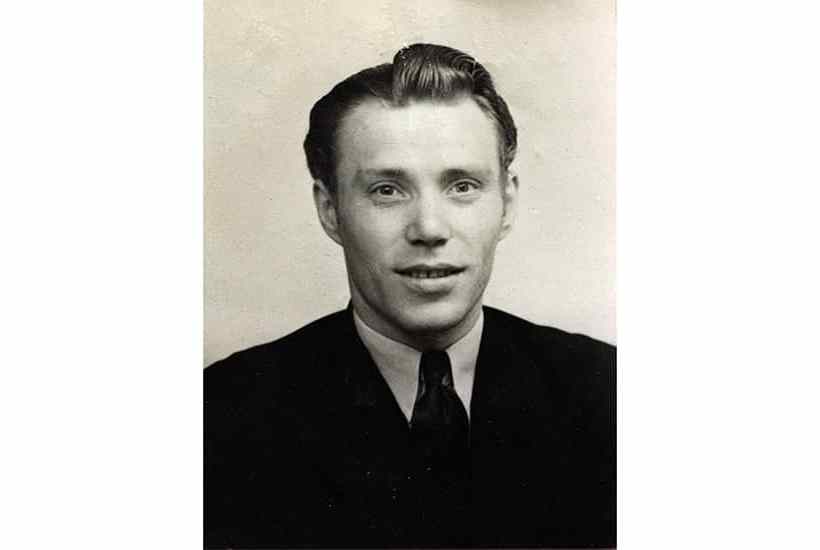

Fedor Zan was 18, working on the river closing sluices, when, on a winter afternoon in 1942, he saw his childhood friend Andrei Sawoniuk standing in a clearing outside Domachevo, their town in Belarus. Sawoniuk had lined up 15 terrified women, all wearing the yellow Jewish star. As Zan watched, hidden behind the pine trees, Sawoniuk ordered the women to strip naked, shot them in the back and kicked their bodies into a newly dug pit.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in