After promising not to raise National Insurance in the 2019 manifesto, the Tories are preparing to do just that in April with their new ‘health and social care levy.’ The levy is set to add £200 to the average worker’s tax bill.

Why have the Tories broken this manifesto promise? Because there was a pandemic, the government says. There was no choice.

Tory MPs are getting antsy. Backbenchers, including former cabinet ministers David Davis and Robert Jenrick, are calling for the National Insurance rise to be postponed or scrapped, as relatively high inflation and the cost-of-living crisis is creating enough of a burden on taxpayers already, even before the new levy kicks in.

Rishi Sunak may hate tax rises, but he hates unfunded spending even more – which is why he continues to support the new tax, which is estimated will raise £12 billion. He subscribes to the Thatcher/Lawson tradition of funding spending plans: not to borrow (as others in cabinet suggested the Treasury should do).

But could the cash needed to pay for the Prime Minister’s social care agenda be found elsewhere?

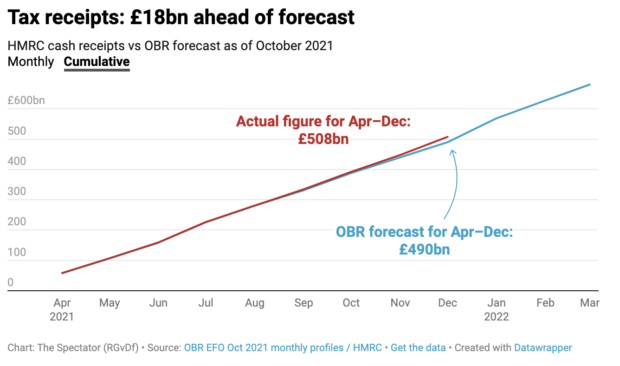

In the leading article of this week’s issue of The Spectator, out tomorrow, we highlight that better-than-expected economic growth has created a cash dividend: tax receipts are roughly £18 billion higher than what the OBR forecast – and comfortably higher than the £12 billion cost of scrapping the National Insurance rise.

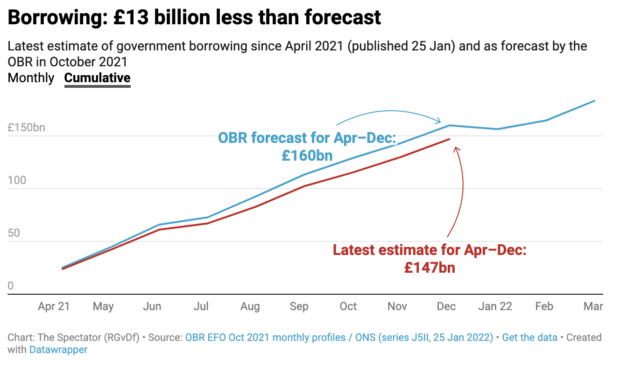

Meanwhile yesterday’s deficit figures from the Office for National Statistics show borrowing over the financial year to December is £13 billion lower than expected by the OBR in October.

That 2021-22 hasn’t been as fiscally disastrous as originally predicted (but is still on track to be the second highest borrowing year in Britain’s peacetime history) will not be enough to convince Sunak that Johnson’s long-term plans to increase nurses’ pay and cover the social care costs of asset-rich pensioners should be paid for in this way. For the Chancellor, there is a crucial difference between pandemic spending and day-to-day spending, and the latter, in his mind, should be fully funded, not borrowed.

But the tax receipts are a different matter. This money isn’t hypothetically conjured up from borrowing: it is real income to the Treasury, and fits much more closely with Sunak’s promise after last year’s Budget that ‘every extra marginal pound’ in future would go to tax cuts.

So will Rishi now be joining those Tories advocating the scrapping of the NI rise? It’s unlikely, not least because the additional revenue may turn out to be a blip, with corporation tax revenue thought to be especially volatile. And as I wrote last year, Sunak’s great fear is inflation. He’s been vindicated in his concerns. We are all paying the price of shutting down and kickstarting the global economy, government included. Interest payments on public debt exceeded £8 billion last month – a December record, as inflation has increased the costs of government borrowing. The way in which UK bonds are linked to RPI makes Britain especially vulnerable to these surges.

It would appear there is increasing opportunity here – not just by borrowing less, but by the economy growing more – to reconsider the NI levy before it’s ushered in. But other considerations make it less likely to go – including Sunak’s core commitment to the principle of fiscal responsibility, which he’d like to instil once again in the Tory party.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in