Yet again, inflation has surged past expectations – this time hitting 5.1 per cent in November, a ten-year high, up from 4.2 per cent in October. This threatens a political crisis as well as tough economic times: unless inflation is quelled, next year will be one of declining living standards for most people. Anyone whose pay is not rising by at least five per cent will, in effect, feel like they’ve experienced a pay cut.

It was assumed that five per cent would be about as high as inflation would go but all this is proving hard to predict. This has gone past the Bank of England’s peak forecast, which wasn’t expected to be hit until next year.

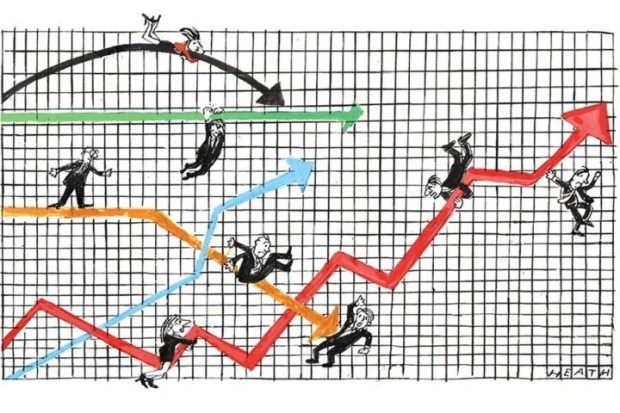

The increase has been largely driven this month by price hikes in transport (motor fuels and second-hand cars), as well as increases in housing and ‘household services’ – costs that are guaranteed to be felt by the public on a daily basis. Once again, the rise in inflation has outpaced market predictions, for which the consensus was around 4.7 per cent. As the graph above shows, the Bank of England, too, has low-balled its predictions for price rises, illustrating the increased difficulty of predicting how fast inflation is surging.

In recent weeks, senior members of the BoE have distanced themselves from their own official forecasts: Huw Pill, the chief economist, told the Financial Times that inflation could hit five per cent in the new year, while Ben Broadbent, the deputy governor, told the same paper that inflation could ‘comfortably exceed’ five per cent next year. Both seemed to spot that the Bank’s forecast from just last month was already out of date, with inflationary pressures building rapidly. But today’s figures will still likely come as a shock – it appears that predictions are struggling to keep up with just how quickly prices are rising.

Will the Bank take quick action to curb inflation? It has the opportunity to do so tomorrow, when the Monetary Policy Committee will vote on whether to hold interest rates, yet again, at a record low of 0.1 per cent, or vote to increase them. Today’s inflation figures will put significant pressure on the Bank to act, but they will be weighed against worries about the economy: with October’s lacklustre growth figure of 0.1 per cent, and now the Omicron variant and renewed restrictions set to knock the economy sideways yet again, the Bank will be balancing inflation with competing concerns that any interest rate hike could stunt the UK’s economic recovery further.

But it’s becoming clear that it’s a matter of ‘when’, not ‘if’ the Bank will need to take action. After nearly a year of central bankers and politicians insisting this inflation is simply transitory – a short blip caused by global reopenings after lockdowns – it is finally sinking in that inflation is back, and it doesn’t need to hit 1970s levels for it to cause real pain to households, and real problems for the public finances.

This has been a concern of Rishi Sunak’s all year: the Chancellor has been using his Budgets to hedge against the threat of inflation, in case a combination of inflation and even a relatively small rise in rates forced him to find tens of billions of pounds more just to service the increased debt. The question now is how quickly others will act, including the Bank, to try and keep inflation under control.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in