If you play chess like a wet rag, sooner or later you will be made to regret it. In Nigel Short’s new book Winning (Quality Chess, 2021), that precept pops up in countless guises, and nobody is above criticism. Peter Leko ‘infamously offended the gods by attempting to draw his way to the title’ in his world championship match against Vladimir Kramnik in 2004. Mikhail Gurevich pursued a ‘craven objective’ in trying to draw his way to qualification at the 1990 Manila Interzonal. (He was undone by Short himself.) Bronstein’s chances against Botvinnik in 1951 perished with his ‘abject capitulation’ in game 23. Russian grandmaster Aleksey Dreev was punished for a ‘wanton act of timidity’. About Chinese grandmaster’s Ni Hua premature draw offer, Short writes ‘If you don’t try to make the most of your chances when they are presented to you on a silver platter, you will never reach the very top.’

Short did not miss an opportunity to skewer himself for an early peace treaty: ‘when you commit a crime against the game of chess, as I did here, the gods have a way of punishing you…’ Later, ruefully, he notes: ‘When you are soaring high, don’t switch off the engine.’ But on the whole, his deliberate pursuit of the combative tendency has distinguished him (indeed the cover portrait shows him with boxing gloves held aloft). Writing of a tournament victory in Hungary, Short notes: ‘Not every win is a result of supreme creativity; some of them are won by fighters.’

These hard-earned nuggets of wisdom are delivered breezily. But Winning is neither an improvement manual nor a conventional collection of best games. Rather, it is an account of eight memorable tournament victories including all the games. That turns out to be a refreshing angle, showcasing the exemplary next to the scrappy, alongside a sprinkling of utilitarian draws, which are richer than the dry game scores would indicate. The heart of the book lies in the vivid annotations and the colourful vignettes of the tournaments and their protagonists. The end result is intensely readable, and Short’s book was highly commended in the 2021 ECF book of the year award, though that prize was awarded to Sergey Voronkov’s Masterpieces and Dramas — a historical account of the intrigues behind the Soviet championships from 1920 to 1937. Happily, both books may beget a sequel.

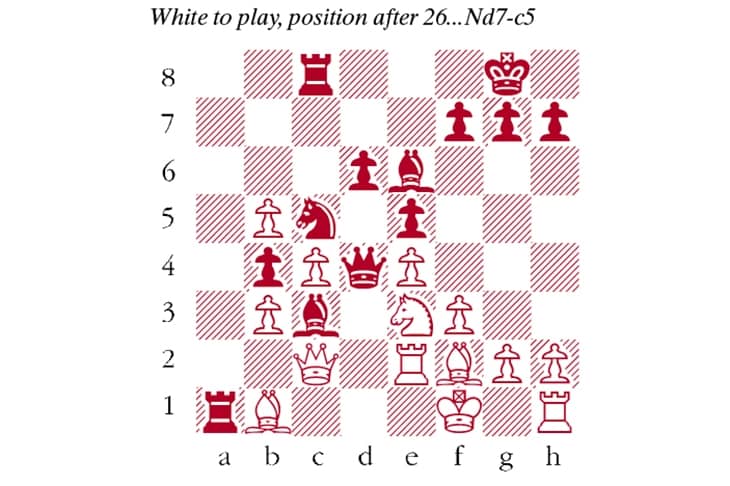

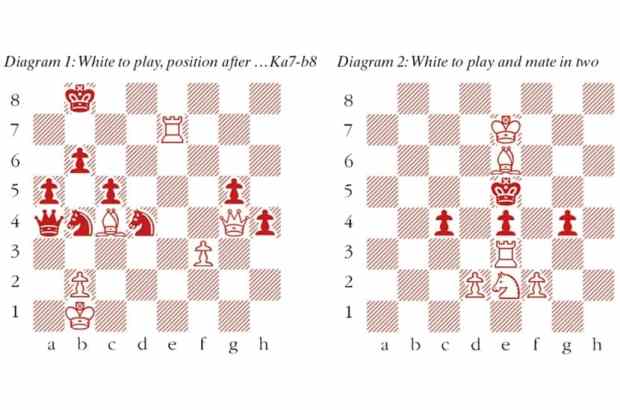

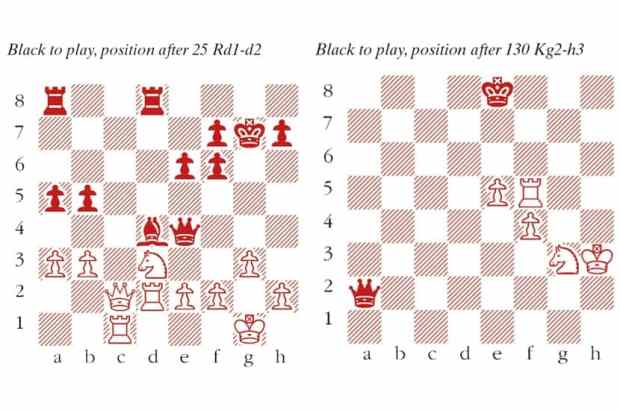

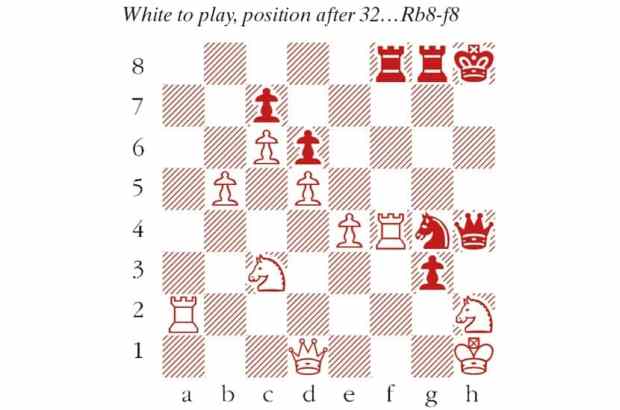

Short’s unflinching approach makes him most dangerous in positions where all three results are possible. In the diagram, from a recent tournament in Sweden, his pieces are contorted but functional, and Black’s queen is in danger. His next move, 27 g4, prepares Kf1-g2, and the game soon spirals out of control.

Nigel Short–Etienne Bacrot

TePe Sigeman & Co, September 2021

27 g4 27 Nd1 Nxb3! 28 Bxd4 Nxd4 leaves Black on top. Nxb3 28 Kg2 Nc5 29 Nd5 Qxc4 30 Ne7+ Kf8 31 Nxc8 Bxc8 32 Ba2 Qxb5 33 Rxa1 Bxa1 34 Bc4 Qb6 35 Bxc5 dxc5 36 Qa2 Bd4 37 Qa8 Qb7 38 Ra2 Ke8 39 Bxf7+ Kxf7 40 Ra7 Qd7 41 Qd5+ Ke7 42 Rxd7+ Bxd7 The passed pawns and bishops are strong, but Black’s king is never safe from harassment. 43 Qg8 Kd6 44 g5 Be6 45 Qxg7 b3 46 Qxh7 b2 47 Qb7 Bf7 48 f4 exf4 49 Kf3 Bc4 The decisive error. Better was 49…c4! 50 g6! Be6 which remains unclear. But not 50…Bxg6? 51 e5+!, e.g. 51…Kxe5 52 Qe7+ Kd5 53 Qg5+ and wins. 50 g6 Bd3 51 g7 Bc4 51…Bxg7 52 Qd5+ wins. 52 Qb6+ Kd7 53 Kxf4 Bxg7 54 e5 Bh6+ 55 Kg3 Bc1 56 Qd6+ Kc8 57 Qxc5+ Kb7 58 Qb4+ Ka7 59 h4 Be6 60 h5 Ka6 61 h6 Bf5 62 h7 Now 62…Bxh7 63 Qd6+ and White forks the Bh7 with check next move. Black resigns

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in