Which is the oldest pub theatre in London? The King’s Head in Islington claims that its American founder, Dan Crawford, established the trend back in 1970. But a rival venue, Penta-meters, above the Horseshoe in Hampstead, maintains that its proprietor, Leonie Scott-Matthews, set it up as a fringe theatre in August 1968. The dispute rumbles on.

Pubs are peculiar to British culture, and their conversion into theatres owes something to the quirks of architecture. Most have a small room on the first floor which is slightly inaccessible from the downstairs drinking area, and it’s hard to tempt boozers to climb a narrow flight of stairs and sup their pints in a cramped space that feels a bit like an attic. But these dank little rooms are ideal for theatre.

Many pub theatres are effectively polytechnics that offer drama school graduates a chance to learn the trade from the ground up. A pub is an ideal starting point because the shows tend to have a small cast, a simple set and few technical complexities. And everyone does a bit of everything. The usher who tears off the tickets may also be the artistic director. If the lighting technician gets hit by a bus en route to the dress-rehearsal, there’ll be enough collective wisdom in the building to get a substitute trained before the opening night.

What pub theatres encourage, in other words, is a spirit of experimentation. And this can pay handsome dividends when a show transfers to the West End. The Play That Goes Wrong began life at the 60-seat Old Red Lion in Islington in 2012. Michael Kingsbury’s production of Maggie & Ted (a historical comedy about the Conservative party leadership) migrated from the White Bear in Kennington to the Garrick last June.

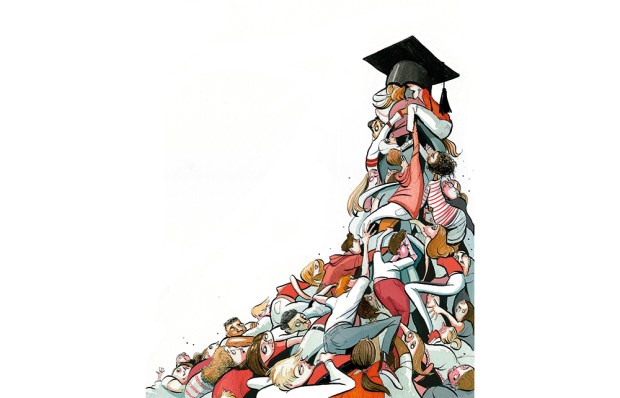

Many of our greatest luvvies began their careers in pub theatres. The Finborough theatre, a pub venue in Earl’s Court, gave work to Kathy Burke, Jane Horrocks and Rory Bremner during the 1980s. Its artistic director, Neil McPherson, claims it has discovered, ‘some of the UK’s most exciting new playwrights including Laura Wade, James Graham, Mike Bartlett and Jack Thorne’. The walls of the King’s Head are lined with photographs of stars who once trod its narrow stage: Joanna Lumley, Hugh Grant, Kenneth Branagh and Clive Owen.

Some upmarket theatres, like Soho and Hampstead, have converted their rehearsal rooms into small ‘black box’ spaces because they want to replicate the special pub-theatre vibe. Low ceilings and cramped seating generate a particular energy and excitement. A venue with just 50 seats will feel almost full with only 25 people in attendance. If 40 punters turn up, the place appears to be rammed and the audience becomes exhilarated even before the show begins.

It’s not just a question of the venue’s capacity. The range of genres at a pub theatre is far broader than the fare offered elsewhere. The Rosemary Branch, in south Islington, is open to virtually anything: ‘We host all kinds of community experiences… theatre, comedy, live music, improv, family shows, puppetry, drag, cabaret, podcasts and burlesque.’

It’s impossible to imagine the Old Vic welcoming such a ragbag of populist entertainment through its doors. And this, in itself, is rather sad because in the 19th century the Old Vic was a music hall that gladly provided lowbrow frivolity for the mass market. Too many theatres in London have become anxious about their status as serious-minded purveyors of ‘must-see’ claptrap which is aimed at metropolitan theatre-goers — the kind of punters who fall asleep during the show so that they’re full of beans when discussing how marvellous it was at the after-party.

A key specialism of pub venues is the rediscovery of forgotten texts. In 2006, the Finborough dusted off a neglected curiosity, The Rat Trap, written by Noël Coward at the age of 19. It was his first play. Five years later, the same venue staged a dazzling revival of Accolade, a minor masterpiece about homosexuality and blackmail by Emlyn Williams. And the Finborough’s production of J.B. Priestley’s Cornelius became a sell-out hit at an off-Broadway venue in New York.

This crucial work of salvage and renewal ought to be done by the National Theatre whose name implies a duty to preserve the UK’s collective memory through its dramatic heritage. But the National’s current managers have lost their judgment and succumbed to a neurosis about race, gender and the rights of anyone claiming to be a marginalised citizen. Here’s what the NT has offered us since August. Paradise was an impenetrable version of Sophocles’s Philoctetes written by the non-binary poet Kae Tempest (who once called herself Kate Tempest). The Normal Heart by Larry Kramer chronicled the lives of downtrodden gay men in New York in the 1980s. Rockets and Blue Lights revealed the connections between the painter J.M.W. Turner and the slave trade. These choices are hardly attuned to the priorities of mainstream audiences.

During lockdown some pub theatres began clamouring for injections of cash from the government. In the end, very little financial help was given, but they seem to have weathered the storm. In fact, a brand-new pub venue in Camberwell, the Golden Goose, opened as a theatre last summer. It’s perhaps a blessing that the pleas for cash went unheeded. Free money comes at a price — compliance.

Pub theatres, like most venues, produce some work in-house but most of their programme is created by external companies who hire the space for a split of the box office. Their budgets are tight so the structure has to be lean and fleet of foot. They can’t afford teams of diversity champions, climate–change gurus and other ornamental hangers-on. And because they’re free of government grants, they don’t need to submit each new work to a panel of nit-pickers who want to know how the show will affect social mobility, rough sleeping and literacy rates in the area.

Autonomy and agility are crucial to their success. They’re highly responsive to new bids from producers. The Hope theatre, above the Hope and Anchor pub in Islington, promises to answer impresarios within three weeks. Getting in touch with the people in charge is never hard. It’s not uncommon for artistic directors to post their personal email addresses on the website. And if you want to have a chat in person you can arrive shortly before curtain-up on a Saturday night and you’ll find the boss perched on a bar stool awaiting the offer of a free pint. That’s not how Rupert Goold runs things at the Almeida. Maybe he should give it a try.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in