What are myths for? Do they lend meaning and value to this quintessence of dust? Like religion, perhaps they help us battle through. In weighing this issue, Charlotte Higgins demonstrates again why the Greek variety have never lessened their grip on the western imagination.

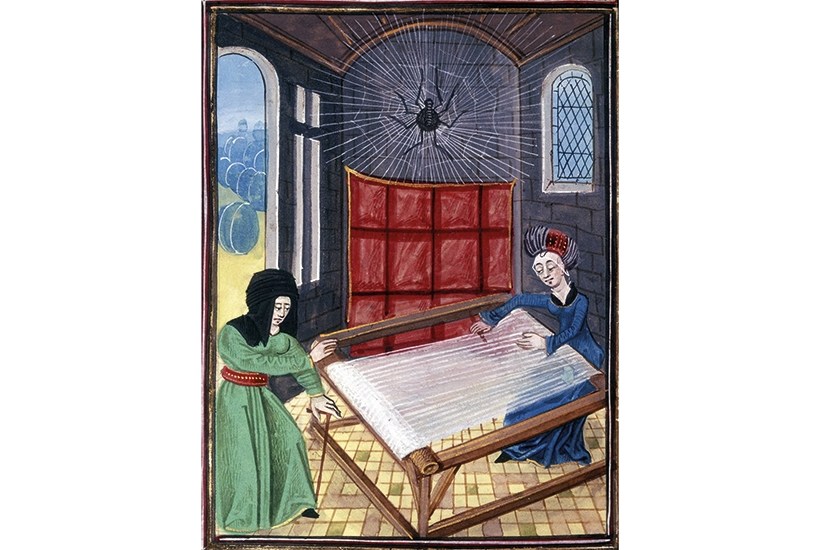

She structures her material around eight women — Athena, Alcithoë, Philomela, Arachne, Andromache, Helen, Circe and Penelope — and in particular around the scenes they weave. ‘I wanted the form of my chosen stories to be expressive in itself,’ she writes in the introduction. And it is. She draws in particular on the rich visual culture that has survived in ceramics, sculpture and frescoes. She also reveals how frequently female characters take control of a story, and how often this happens through the act of weaving, thus highlighting the central role of textiles in the ancient world. The word ‘text’ derives from Latin texere, meaning to weave or compose.

A classicist and now a Guardian journalist, Higgins sticks closely to the original material. These are not retellings in a contemporary setting, like Michel Faber’s (rather wonderful) recent recasting of Prometheus, which features spiteful Amazon reviews and fragments of pizza. We are in the hands of a fine, fluent storyteller (‘Are you ready? Then follow me’), who is properly attuned to what characters look like: Thracians are ‘pale, tattooed, trouser-clad’ and when we first spot Athena, ‘her muscular hand would send the patterned whorl whirling’. Throughout, Higgins deploys direct speech and rhetorical devices such as alliteration and repetition with a light touch, the celestial loom in the Athena chapter ‘so wide that even she, a goddess, must walk up and down, up and down’.

The use of the vernacular is judicious and entertaining. Zeus is ‘at a loose end without his thunderbolts’; a maenad transforms ‘in the blink of an eye’; and Psyche, marooned in the dark, hears ‘a soft, sexy voice’. Wisely refraining from modern jargon, Higgins catches the rhythm of oral poetry, including its bathetic asides: Artemis takes offa sweat-soaked tunic, ‘if goddesses can be said to sweat’. Like the ancients, the author addresses the reader here and there: ‘Our lives are full of choices… Whether to keep to the path or to walk into the trackless forest.’

The book joins many recent considerations of Greek myths from a female standpoint. Gifted novelists have gleefully mined the field, memorably Madeline Miller and Pat Barker, and some have done so in non-fiction, notably Natalie Haynes with the splendid Pandora’s Jar. I could have done with these books some decades ago. My Homer tutor at Oxford was a 93-year-old bachelor-reverend who often told me, in what I recall as iambic pentameters, that he doubted a female undergraduate had the mettle for epic poetry.

Source material does not slow the narrative energy. Higgins explains in 30 pages of endnotes what she has combined, simplified, borrowed and ‘left open’, indicating, too, where certain key ideas — for example, that humankind is simultaneously magnificent and destructive — are most eloquently laid out in ancient works. She cites a transgender classicist when parsing the Ianthe and Iphis myth — one beautifully, even movingly, told here: ‘Whatever form love’s metamorphosis had taken — that was theirs to know.’

These stories speak across millennia, which is why we keep telling them. In her selection, Higgins is especially alert to lines which ring true today. When people’s flocks expire in the fields and frost withers the crops, the ‘shrewd and selfish’ among mortals ‘snatched more grain than they needed, and hoarded it, and shored up their own power’. After pestilence descends, ‘those who lived in crowded quarters were the most likely to sicken and die’. Why go to war, the narrator wonders, as the Greeks lay siege to Troy, reflecting that the kidnapped slave girl Briseis, like Helen herself, was ‘just another pretext. In reality it was an old story, one of the oldest: men locking horns over power and status’.

Higgins, like the bards who first unspooled these tales, creates the illusion of spontaneity (‘And now what?’) and handles suspense brilliantly. Will Orpheus not turn round just this once? Chris Ofili’s drawings complement the lyricism of the prose descriptions.

So here they come again, our distant ancestors, parading their fallibilities just like us. Men drone on with ‘meaty breath’, indecision paralyses (‘almost at once he wrote a second letter to Clytemnestra, telling her the wedding was off’) and the human heart will have its say: ‘Father,’ Phaethon tells Helios quietly, ‘I don’t want a gift. I just want to know that you love me.’

Higgins depicts art mediating life — the reason, I think, that we read books. Helen wove the war obsessively, we learn in the final chapter, ‘as if it might give up its brutal mysteries once she transformed it into thread-made images’. There is no mystery to unlock, of course, no escape from the muddy suck, but myths help us pretend otherwise, at least for a while. I loved this book.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in