There is something bizarre about a sporting event designed to bring people and nations together but from which spectators have been excluded. Most foreigners are currently forbidden from setting foot inside Japan, let alone inside the Olympic stadium. In many senses, Tokyo 2020 — which like the Uefa Euros retains its original name, despite a year’s delay — encompasses the worst of our pandemic-ridden world: the global elite can attend while the rest of us have to settle for watching it on TV.

Yet a successful Olympics — even a week in, it looks as if the Tokyo Games will be judged a kind of success — could provide the impetus the world needs to re-establish normal working relations. In reminding us of what we have lost over the past 18 months, it might spur us on to escape the insularity the pandemic created before it is allowed to become a permanent feature of our existence.

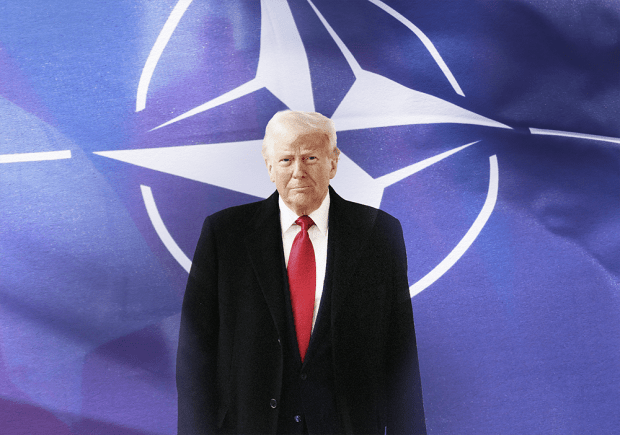

It is ironic that the pandemic was preceded in Britain by a charged political debate over national isolation. Many who campaigned to remain in the European Union accused Leavers of having a drawbridge-up mentality, of trying to cut Britain off from the rest of the world. In America, too, Donald Trump was attacked for isolationist policies. Such attacks had a point: to pander to isolationism would be a tragedy for globally minded countries like the US and Britain.

Yet when Covid arrived, the isolationist instinct prevailed throughout the West. Many of those who were most critical of tough immigration policies and withdrawal from trade deals and trading blocs have turned out to argue the loudest for closed borders. When President Trump first announced he was going to close America’s borders to European travellers, the EU complained bitterly. The bloc failed to notice that, even as it issued its protests, its own member states were busily closing their own borders to each other, Schengen agreement notwithstanding.

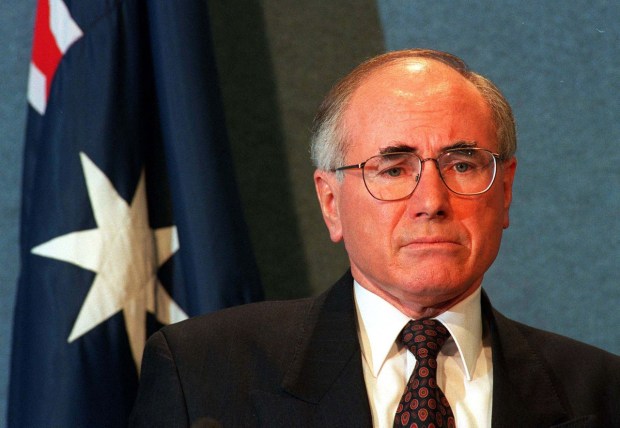

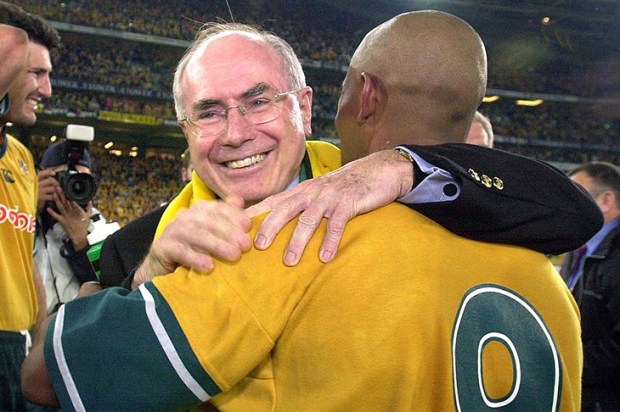

We now see the Biden administration refusing to open a UK-US travel corridor in spite of high rates of vaccination in both countries. New Zealand has become almost as much of a hermit kingdom as Edo-era Japan. Given these countries’ low levels of vaccination, the policies of Australia and New Zealand have a certain logic. But the isolationist trend is also evident in Britain. Some 92 per cent of adults in England and Wales have antibodies, yet there are still calls to close borders because of the hypothetical threat of a vaccine-dodging variant.

After great national traumas, an isolationist instinct often prevails. Following the Great Depression, America declared that it would no longer get involved in any affairs of the outside world. This had calamitous results. There is a risk that the lockdown mentality may linger too. While lockdowns have a strong but immeasurable effect in controlling a pandemic, they have had a calculable effect on global trade and Third World poverty. The knock-on effect of all this may yet claim more lives than the pandemic itself.

Many governments and businesses have started to engage in socioeconomic policies which assume the new insularity will last once the pandemic is over. Supply chains are being shortened, domestic production encouraged. Food and energy security policies are being sharpened. Some of this makes sense: the pandemic has exposed the need for more factories which can produce vaccines and PPE. But the essential rules of global economics have not been changed by the pandemic. Insularity makes everyone poorer, less secure and less free.

The vaccine has downgraded Covid to the point where even a wave of infections the size we have just experienced would not come close to overwhelming hospitals. The acute risk has gone, but emergency government powers remain. Those who attempt to travel abroad are subjected to Byzantine rules which are apt to change with little or no notice. Trying to remember which countries are currently green, amber or red on the government’s list has become all but impossible. Moreover, when the rules change it is a struggle to determine the reasoning behind it. Countries with infection rates much lower than Britain’s are suddenly treated as if they are plague villages. Travellers are made to isolate themselves in spite of repeated tests.

It is too easy to imagine the world settling down into a semi-permanent system of bio-secure bubbles. Some have started to claim that even when this pandemic is over, we will be on the cusp of a new age of pandemics or that such restrictions will be needed because of global warming. It is possible that rules dreamt up mid-crisis could become part of our precautionary infrastructure, with trade limited and mass travel discouraged.

When Tokyo won the battle to host the 2020 Olympics — a short straw if there ever was one — it did so in the hope of showing itself off to the world, just as it had shown off its new bullet train at the 1964 Olympics. Tokyo was to have welcomed tourists in their tens of thousands, winning admirers who would be inspired to return there for business and pleasure. Instead, it has offered a sobering glimpse of what the future in a closed world might look like. Hopefully this will jolt all participating countries into committing themselves, sooner rather than later, to a return to the free and open world we knew until so recently.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.