Antiquaries have had a bad press. If mentioned at all today, they are often derided as reclusive pedants poring over details of manuscripts and shards with little relevance to the wider world. As recently as 1990, the respected ancient historian Arnaldo Momigliano skewered their pretensions when he described them as ‘interested in historical facts without being interested in history’.

Rosemary Hill, the biographer of Augustus Pugin, the architect of Gothic revivalism, which owed much to antiquarianism, has other ideas. In this engaging survey, she shows how antiquaries’ interest in fields such as coins and heraldry actually enhanced the study of history, notably around the time of the French Revolution, when the spirit of Romanticism encouraged new ways of looking at the past.

This kept historical enquiry alive in what Hugh Trevor-Roper suggested in his influential essay ‘The Romantic Movement and the Study of History’ was a period of hiatus between the lofty rationalism of Enlightenment practitioners such as Gibbon and early Victorian crowd-pleasers such as Macaulay, whose ‘social history’ incorporated ballads, songs and other lighter findings of antiquaries as he sought for his work to ‘supersede the last fashionable novel on the tables of young ladies’.

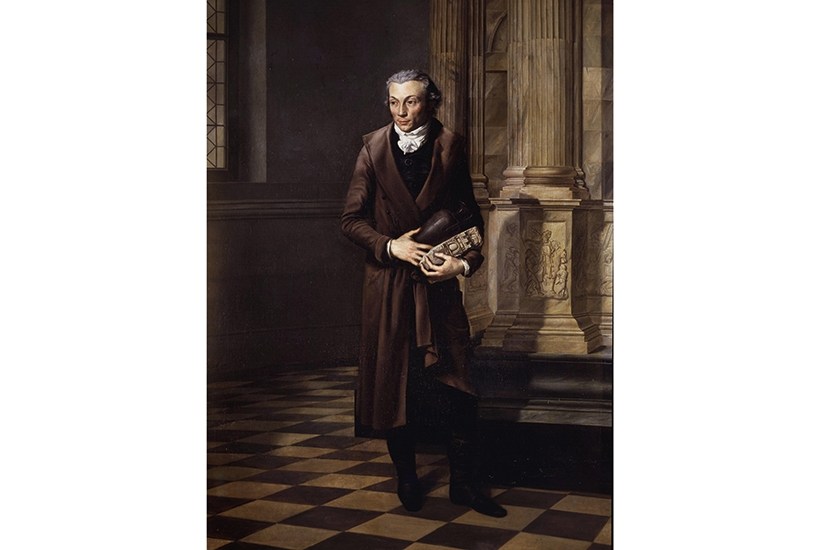

Hill starts with two towering pioneers of post-Reformation English antiquarianism, William Camden and William Dugdale. The former dispelled medieval myths in his 1586 survey of national history, the Britannia. The latter delved into a contentious area that Camden had tactfully avoided when he examined the foundation charters of all pre-Reformation religious houses in his Monasticon Anglicorum of 1655.

Such subject matter spurred an enduring criticism of antiquaries — that, in admiring medieval and particularly Gothic architecture, they were closet Papists bent on reversing the narrative of post-Reformation English history. But antiquaries could not help being contentious. Walter Scott refers to their ‘bitchiferous’ nature. In the late 18th century, the architect James Wyatt drew their wrath with his practice of embellishing buildings, including Salisbury cathedral, where he banned them from entering the precincts and was himself initially blackballed from joining the Society of Antiquaries.

By then Romanticism was being filtered into the intellectual mix, requiring a new, imaginative dimension to the interpretation of the past. The results are difficult to pin down, but basically it meant giving legitimacy to more obscure byways of history, encouraging a sense of the picturesque, and calling on hitherto neglected disciplines, such as the study of costume and theatre.

Just as influential were the political consequences of the French Revolution. The Jacobins’ new national museum at the Louvre was predictably Classicist. Medieval art and architecture were dismissed as tainted relics of church and crown. When the citizens of Rouen voted to destroy their cathedral’s episcopal throne, stating ‘this Gothic monument is equally offensive to good taste and to the principles of equality’, the only dissenter, a Monsieur Roger, was dispatched to the guillotine. Hill abjures parallels with pulling down statues, but they are there.

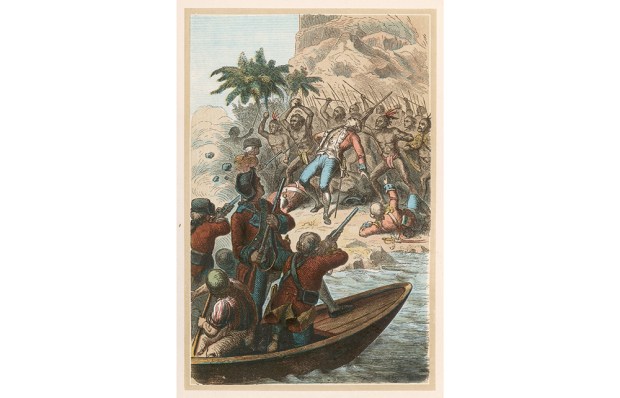

Luckily there were heroes of the moment, such as Alexandre Lenoir, who somehow managed to establish the Musée des monuments français close to the Louvre and cram it with material gathered from monasteries. As a result, Paris in the Terror unexpectedly became a mecca for British antiquaries seeking historical artefacts, a process which was redoubled following the fall of Napoleon. The seafaring Pugin used his own boat to cross the Channel and ferry medieval loot back to his house in Ramsgate. Recently established auction houses in London flourished.

This led to a renewed exploration of the matter of England. It was possible to travel to Normandy where the Bayeux tapestry was removed from its roller, restored and studied with the benefit of antiquarian disciplines such as heraldry to confirm its post-conquest dating and even the shot to the eye supposed to have killed King Harold.

The dating of Gothic architecture became more precise. Ancient texts including Beowulf were published for the first time. Shakespeare succumbed to antiquarian scrutiny, as places associated with him were ‘re-edified’ and ‘sophisticated’. North of the border, Walter Scott breathed new and romantic life into Scottish history with his Waverley novels, one of which, The Antiquary, drew on the spirit of Don Quixote to idealise the figure of the solitary scholar.

Scott crucially stirred his ‘fat friend’ the Prince Regent to allow him to search for the lost Scottish regalia and, on ascending the throne as George IV, to visit Scotland on a royal tour which glorified his Scottish antecedents. Tartan, which had been banned until recently, became de rigueur. Scott’s goal of reconciling Unionism and Jacobitism had been achieved.

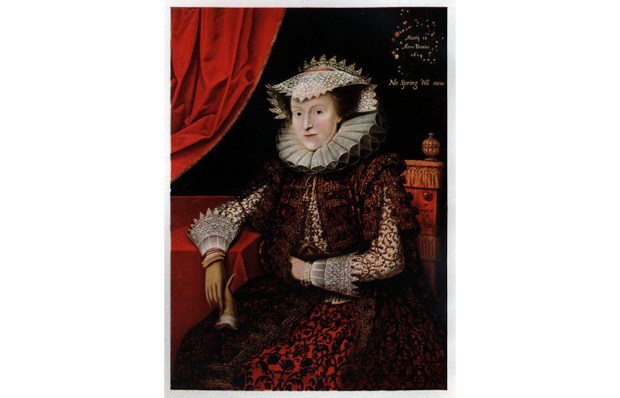

This even survived the antics of two pantomime villains, the Allen brothers, John and Charles, who, after time on the continent, took the surname Sobieski Stuart and claimed to be the legitimate heirs of another romantic, the young pretender Bonnie Prince Charlie. As antiquaries in 1842 they published the Vestiarium Scoticum, supposedly an 18th-century manuscript describing the origins of the tartan. Like the works of Ossian 80 years earlier, this is now regarded as a complete fabrication — but not before it was praised by Queen Victoria, whose love of all things Scottish soon extended to buying an estate at Balmoral.

By then the new antiquarianism had made its mark, and in 1850 the British Museum opened its doors to non-Classical art and became a true national institution. No sooner was that achieved than the wheels turned again. The antiquary of the popular imagination was no longer the romantic figure of Scott, but George Eliot’s old stick Casaubon, and the practice of history reverted to its default position as a masculine record of politics. A century later came another change, and history began to explore new fields in the manner of the antiquaries.

Hill’s subjects have a built-in propensity to dryness. But marrying scholarship and sensibility, she steadily convinces of the importance and often excitement of their endeavours. In the process she achieves her stated aim, echoing Camden in his Britannia, of restoring history to the antiquaries and the antiquaries to history.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in