Rumours reach me that the libel report for Stephen Bayley’s forthcoming biography of Terence Conran was longer than the book itself, so I’m hazarding a guess that Bayley has siphoned off contentious material into this purported fiction. For as he says here, kidding on the level, ‘all novels are memoirs, all memoirs are novels’, and as Conran was Bayley’s colleague at the Boilerhouse Project at the V&A, the boys indeed have ‘previous’.

If the hero of The Art of Living, the brilliantly drawn Sir Eustace Dunn, is indeed Sir Terence, he comes across as a sly old fox who ‘betrayed everyone he knew’ and ‘never said please or thank you’. Though he became ‘Britain’s best-known designer’, the complete catalogue of his works, we are told by the narrator Rollo Pinkie bitterly, ‘is a very thin volume’.

His genius, rather, is for appropriating other people’s ideas and schemes — most notably buying up skillets and whisks, garlic presses and asparagus kettles in France and selling them in his chain of British shops, Habitat in all but name. ‘If you can’t afford a good de Kooning,’ says Dunn, echoing Conran, ‘you can probably afford a good salad bowl.’

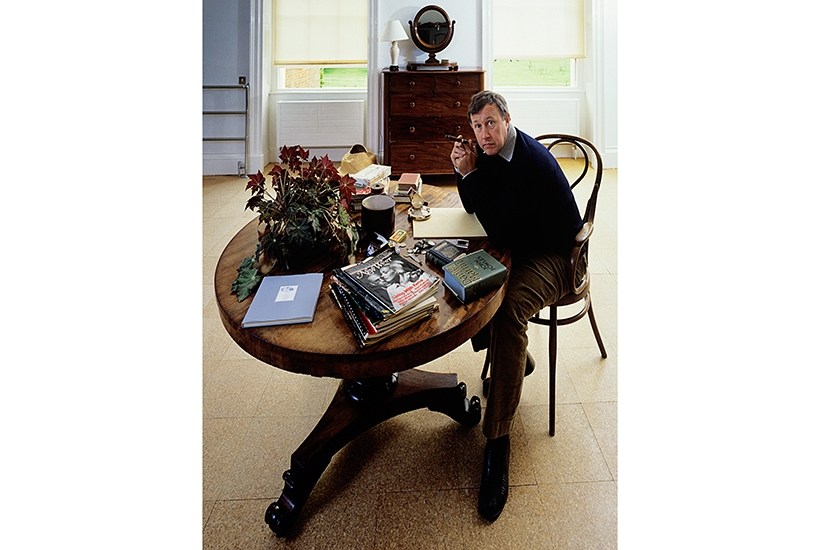

Cigar-chomping Sir Eustace has a few meals with Elizabeth David and nicks her recipes for his restaurants. ‘Dinner,’ we are told, ‘should be decorative and romantic, not a nutritional chore.’ Like Conran, Dunn situates his eateries in novel premises — a Friese-Greene cinema, a tobacco warehouse, a Quaker Meeting House.

There are evocative descriptions of the post-war murk — semolina and cabbage — out of which Dunn emerged, and which he sees as his life’s work to eradicate or transform, getting shot of ‘hideous reproduction art and detestable, fussy knick-knacks’ in favour of cool Scandinavian ceramics, tubular steel furniture, Japanese paper lanterns and ‘fishermen’s chairs from the Ligurian coast’.

There’s nothing that can’t be improved by good design is Dunn’s view. Life ought to be a search for ‘transcendent beauty’, which, as the Holy Redeemer of Domesticity, he locates in scented candles, a Bentley Mark VI saloon, the cabin upholstery in a BOAC Boeing 377 Stratocruiser, John Minton book jackets, onion-skin writing paper and Italian-made chrome espresso machines.

The pages are full of Wildean paradoxes: good taste is tasteless (e.g. the Duchess of Windsor ordering military drums from Harrods to turn into coffee tables); ugliness is beauty, or has its own beauty; overt ambition is a form of lazy self-regard; suburbanites are the most metropolitan; and ‘not to be well-dressed was an insult to other people’.

When matters get pretentious — ‘making a decent cup of coffee is as important as writing a symphony’ — Francis Bacon materialises to undercut the balls. Style and fashion, he declares, is simply the business of ‘telling imbecile women what colour to paint their cornices’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in