In Chesham and Amersham last week, Tory voters punished the government, not only for building on greenfield sites, but for allowing the construction of too many ugly, badly designed buildings. The British public are fed up with modern architecture. Despite polls that prove this time and time again, architects simply ignore people’s views. Indeed, if the public has the temerity to criticise their latest works, there is uproar — as I have discovered to my cost.

At a dinner in late 2019, I asked Norman Foster, the ‘starchitect’ of such things as London’s widely derided City Hall and the Berlin Reichstag, if he was pleased by the government’s new Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission. The commission’s mission was to ‘tackle the challenge of poor-quality design and build of homes and places across the country’ and to ‘ensure popular consent’. It was chaired by the late Sir Roger Scruton. How wrong I was to assume that Foster would applaud the initiative. Refusing to discuss it, he lost his temper, spewed ridicule on Scruton and stomped away.

But Foster’s response is not unusual. The chasm is widening between what people want to enhance our cities, our countryside and our lives and what architects are giving us. And now a massive building programme is planned all over England — similar to the reconstruction effort after the second world war.

During the pandemic, the government announced a White Paper, backed up in the Queen’s Speech, which pledges more house-building. Ominously, it included a new algorithm (since abandoned) telling councils how many homes to build, with the Cotswolds a particular target. Sir Geoffrey Clifton-Brown, the local MP, has spoken out against over-development. Yet he failed to make his case by citing pertinent examples.

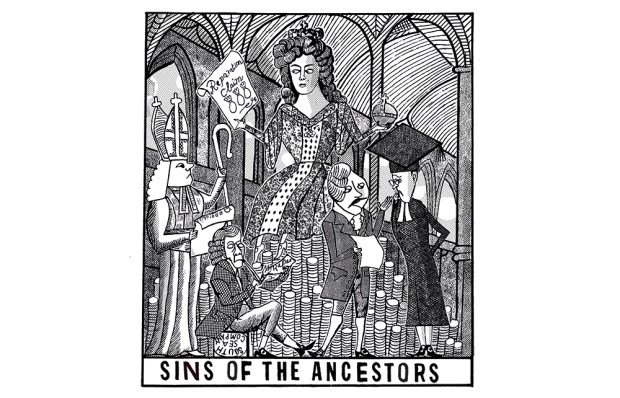

One is Quenington, the Cotswold-stone village (with houses both ancient and modern) where I live, near Cirencester. This year, a property developer put forward a revised application for a vastly oversized, inappropriately positioned house that will loom grandiosely over nearby 17th–century cottages. Another example is the beautiful — and now endangered — 18th–century Bathurst Park estate, inherited by the 9th Lord (Allen) Bathurst. An architect is set to build 2,350 soulless new homes on its fields on the edge of Cirencester, increasing the size of the overbuilt market town by as much as 40 per cent. In an angry demonstration following the council’s meeting, Lord Bathurst escaped a citizen’s arrest by the skin of his teeth.

Ironically, it was an earlier Lord Bathurst who had the foresight to establish a school of sympathetic architecture. He knew how necessary it was to consider the impact of new building on the environment. His understanding sprang from his relationship with Ernest Gimson, a 28-year-old man who arrived on his doorstep in 1893, looking for work. Bathurst offered him one of his Sapperton houses at a low rent if he would repair and restore the property.

Gimson completed the task with such sensitivity and respect for the landscape that he and his colleagues were soon offered other projects. Their reputation for harmoniously integrating new buildings quickly grew. This appreciation of how a building relates to its surroundings lay in their training. Every apprentice then was expected to study the history of architecture as an essential foundation. Students were encouraged to study craft techniques and draw old buildings and churches in order to gain a knowledge of artisan skills. Crucially, apprentices were taught the virtue of simplicity.

Gimson and his circle of socialist architects — such as John Ruskin, William Morris, William Lethaby, Philip Webb, Detmar Blow and the brothers Sidney and Ernest Barnsley — excelled at marrying simple, functional design with skilled craftsmanship. The result was that Nikolaus Pevsner, the post-war arbiter of architectural taste, described Ernest Gimson as ‘the greatest of the English architect-designers’.

Never have Gimson’s skills, and those of his circle, been so needed. Were he alive, he would scoff at many of our contemporary architects’ ill-conceived plans, knowing they will destroy the entire character of a place.

One look at Dezeen, the international modernist architects’ favourite website, reveals the mismatch between their concept of beauty and the public’s. The plans for Bristol University’s new library have been highlighted by the site as a shining example of civic architecture. Yet these plans were condemned by local people as ‘an atrocity, a new unwanted landmark… absolutely horrific’. Despite this, in March the councillors voted the building through 6-4.

Take two more examples of monstrous new developments forced through by building planners and councillors who rode roughshod over community concerns. First, a nine-storey glass and steel development in Old Brompton Road. Despite carefully argued criticisms and protests, the community’s feedback was totally ignored by Kensington and Chelsea council. The sequence of events was distressingly but brilliantly exposed on a blog called From the Hornets Nest by a writer called ‘the Dame’.

Then there is the £1.3 billion Olympia London development, which will sprawl across a historic site of 14 acres. The landmark exhibition centre is affectionately known as the home of the International Horse Show and Spirit of Christmas Fair, among many other annual events. Yet it is being transformed into a gigantic eyesore, comprising a multi-storey office block, hotel, concert hall, bars, restaurants, theatre and shopping mall, with poorly thought-through infrastructure that will bring local traffic to a standstill. The developers have refused to listen to the concerns voiced by residents. ‘Lateral solutions have had to be found,’ says Mike Hitchens of Pell Frischmann, the engineering consultancy working on the project. ‘Yoo Capital [a major funder] has been constantly asking us, can we do this, can we do that? We’ve had lots of fun re-imagining this space.’ It may be fun for the architects and developers, but it is not amusing for the people who have to live in or near their creations.

But Britain does have talented modern classically trained architects and planners. Now is their time to come to the forefront and for building planners to employ them. After Sir Roger Scruton’s death, Nicholas Boys Smith has written widely on planning, and the proven links between good design and wellbeing. If the pandemic has taught us anything it’s that collaboration makes for a happier, smoother-running society. It is therefore disturbing to be emerging from lockdown into a world in which architects ignore residents’ wishes and needs, treating them as lab rats in their experimental building schemes while they rake in the money.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in