At the risk of encroaching on Spectator Competition territory, what is the least surprising thing for any given narrator in a particular author’s work to say? (For one of Irvine Welsh’s, a single word of four letters might be enough.) In the case of Patrick McGrath, I’d suggest, the answer comes on page 55 of his new novel: ‘I confess I feel that my sanity is under threat.’

McGrath famously grew up in the grounds of Broadmoor, where his father was the medical superintendent, and his consequent lifelong interest in psychiatry is reflected in pretty much all of his fiction. As a rule, if you’re a McGrath protagonist, you’re likely to be suffering from some sort of serious mental illness — often, for some reason, with a side order of repressed homosexuality.

Both these elements are duly present again here, together with two of the newer concerns from McGrath’s previous novel The Wardrobe Mistress: namely fascism and ghosts. The main character of that book, set in post-war London, was haunted (perhaps literally) by her dead husband who she then discovered had been an Oswald Mosley supporter. In Last Days in Cleaver Square, the fascist ghost haunting the narrator Francis McNulty is just as ambiguously presented, but this time a lot better-known.

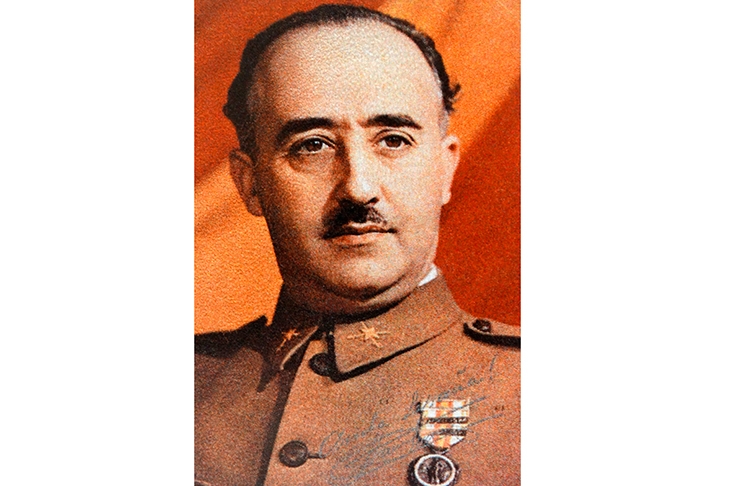

As a young man, Francis fought with the International Brigades in the Spanish civil war. Now, as an old one — older, in fact, than strict chronology would seem to allow — he’s living in London in 1975, and having visitations from General Franco. Which might be mysterious enough even if Franco weren’t still (just about) alive in Madrid.

So is Francis right to worry about that sanity of his? Certainly his daughter Gilly thinks so, treating him with the customary mixture of tenderness and condescension shown to the elderly. For the reader, however, matters aren’t so clear-cut. Francis has moments of obvious senility, but as McGrath narrators go, his mental illness seems fairly mild. Indeed, the novel leaves open the possibility that his Franco sightings might be in some sense real: if not a product of the supernatural — although that’s not entirely ruled out either — then of the supernatural’s traditional rival, the subconscious. Nearing the end of his life has evidently had the effect of clarifying what’s ultimately meant the most to Francis: not only Spain but also an American doctor he met there (‘The only man I ever truly loved’) who was shot on Franco’s orders.

The trouble is that having put in place this intriguing set-up, McGrath leaves it to drift for far too long. Francis keeps seeing Franco. Gilly keeps telling him he can’t have done. Francis keeps saying he did. Above all, he keeps remembering the same few incidents over and over again in a way that, while psychologically plausible, makes it increasingly hard to disagree with Gilly’s verdict that he spends ‘too much time thinking about this stuff’.

And for long stretches in the middle of the book that’s about it, with little sense of narrative propulsion, or even of deepening — rather than simply repeating — what we knew by about page 50. Only towards the end does the book regather momentum, when Francis returns to Madrid shortly before Franco’s death.

McGrath’s prose is as unshowily affecting as ever and Francis himself a memorable portrait of raging against the dying of the light that never lets us forget how inexorably the light dies anyway. Nonetheless, while Last Days in Cleaver Street offers much to enjoy and is by no means a long novel, the feeling persists that it might have offered even more as a considerably shorter one.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in