Charles Péguy’s adage that everything begins in mysticism and ends in politics is sharply illustrated by the development of the Irish Revolution. In his previous scintillating studies, Easter 1916: The Irish Rebellion and The Republic: The Fight for Irish Independence 1918–1923, Charles Townshend traced the progress of Ireland’s long-drawn-out severance from Britain. The completion of the trilogy is delivered with his characteristic scholarly panache. And by foregrounding how Northern Ireland came into being in 1920–21, and was sustained by the notable fudge of a non-delivering Boundary Commission in 1925, he brings into unforgiving focus the carelessness, double-dealing and myopia which has bedevilled Britain’s government of Ireland, so spectacularly demonstrated in our own day by the current impasse over Northern Ireland’s treatment under Brexit.

Townshend’s study reaches back to the emergence of Home Rule at the forefront of British politics in the mid-1880s, and the early exploitation of Ulster’s resistance by the Conservative party — spearheaded by Lord Randolph Churchill in 1886 and followed by equally opportunistic political descendants. They had potent material to work with: the intransigent and exalted creeds of Orangeism and Unionism, described by one contemporary observer in terms of jihad, and characterised by Townshend in one of his succinct sub-heads as ‘vigilantes and vanguards’. Opposition to Home Rule was an article of Ulster Protestant faith, and guerrilla street politics in Belfast had become an established expression of anti-nationalist and anti-Catholic feelings well before the turn of the century.

What is less clear is when the idea of Ulster going it alone became an accepted option. When the third Home Rule Bill actually managed to pass into law during 1912–14, violent paramilitary resistance was threatened in the north-east, and most Unionists in the rest of the island (slow learners, as ever) assumed that this agitation was holding the ring for keeping the whole island in the Union. But the idea of Ulster as a partitioned entity was floated as early as 1911, and firmly lodged on the agenda by 1914; the epic record of the Ulster Division on the Western Front and the 1916 Rising in Dublin helped fix this in stone, and the leaders of Ulster Unionism grabbed it with brutal alacrity.

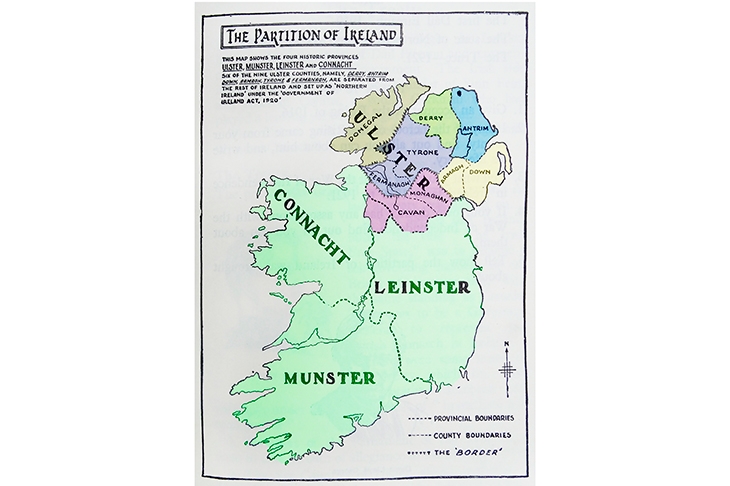

The meat of Townshend’s book lies, first, in the negotiations that led up to the Government of Ireland Act in 1920, which set up the statelet of Northern Ireland and a devolved government in Dublin for the rest of the island (by that time inflamed by rebellion and martial law); then in the developments whereby the Home Rule government established in the north solidified into being, while that designated for Dublin was predictably ignored by the revolutionaries; and finally in the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty’s grant of a much larger autonomy to the southern unit, while leaving the future of Northern Ireland to a promised Boundary Commission.

This study pays close attention to the often surprising route whereby a six-county unit was preferred to the traditional nine-county province of Ulster, and the guaranteed Unionist majority which this entailed. Townshend is as unsparing about the myopia of southern nationalists towards their northern brethren as about the unlovely excesses of the Ulster Unionist leaders and the ‘Ulsteria’ which they manipulated. Though a few nationalist intellectuals argued for the inevitability of partition, ‘the Dáil’s attitude to Ulster oddly resembled the baffled indifference to Ireland so long evident at Westminster’. And Townshend’s deconstruction of Lloyd George’s forked-tongue manoeuvrings between his Conservative coalition colleagues and the leaders of the Irish delegation to the Treaty negotiations makes it all too clear that the expectations held out for the Boundary Commission by nationalists were based on drastic economies with the truth as practised in Downing Street.

From early on, Ulster Unionists had been assured that the province’s position was to be protected, while nationalists were led to believe that the Commission would radically shift boundaries in their favour. In fact, its draft recommendations in 1925 were not inconsiderable. With boundary changes affecting East Donegal, Fermanagh and South Armagh, 183,000 acres (and 31,000 people) would have gone to the Irish Free State, and 49,000 acres to Northern Ireland — possibly diluting, though not defusing, later Troubles (Crossmaglen would have been in today’s Republic). But a leak to the Tory press and the resignation of the out-of-his-depth Irish representative led to a hasty cover-up. Even these limited recommendations were buried, and the Northern Irish state was entrenched —though it had been expected by many in the early 1920s to be a short-lived phenomenon.

That expectation was based on a great deal of wishful thinking — as was Sir James Craig’s claim that sectarian relations in the province were unproblematic (‘a Protestant doctor had recently opened a Catholic bazaar and Lady Craig had been asked to a Catholic whist drive’). More viscerally, the Commission was decisively torpedoed by nobbling its chair, Sir Richard Feetham, when Winston Churchill released a 1922 letter from Lord Birkenhead (then lord chancellor) to Balfour asserting that under the Treaty articles the Commission could not change the fundamental ‘proviso’ of Northern Ireland’s territorial status quo, let alone rectify anomalies of allegiance among the unwilling Catholic minority.

Townshend calls his chapter on the Commission ‘The Fix’ and his chosen word for Churchill’s manoeuvre is ‘shady’. This seems the mot juste — as it is for the blatantly conflicting promises about a ‘border in the Irish Sea’ in our own times, eviscerated in the laconic but conclusive epilogue to this book. As the lies of the current prime minister (far more flagrant, careless and open than Lloyd George’s) come under scrutiny while buses burn and policemen are assaulted on the streets of Belfast, it seems a salutary moment to look back at the events surveyed in The Partition, and conclude that the politics which replace mysticism surely need not be quite as shameless, opportunistic and inadequate as this.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in