When Mao’s Red Guards first got to work in China, they defaced statues before they tore them down. It was common to find a statue of Buddha, for example, with new signs saying: ‘Destroy the old world! Establish a new world!’ Boris Johnson’s government isn’t keen on statue removal, but it is offering a compromise. Oliver Dowden, the Culture Secretary, has adopted a policy of ‘retain and explain’, whereby the statue remains but with a plaque giving more historical context. Explanation, it is assumed, can only be good.

Yet you only have to look at the single case where ‘retain and explain’ has been deployed to see what we could be in for. Edinburgh City Council has had its planning application approved to attach a plaque to the Melville Monument in St Andrew Square commemorating Henry Dundas, Viscount Melville, First Lord of the Admiralty. The contention is whether he delayed the abolition of the slave trade by inserting the word ‘gradual’ into the 1792 motion on the issue.

A reasonable interpretation of his addition is that it ensured the Act’s passage. You might think Dundas’s record of advocacy for a transported slave, by which he proved Scots law would not uphold the institution, would be worth taking into account. Not according to the wise men of Edinburgh City Council. Their revision says Dundas was ‘instrumental’ in deferring abolition. It concludes with a gross distortion: ‘In 2020 this was dedicated to the memory of more than half a million Africans whose enslavement was a consequence of Henry Dundas’s actions.’

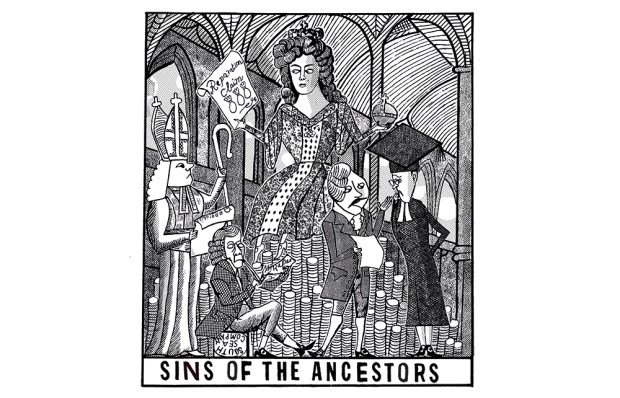

Given that the council didn’t commission a historian to draft the wording, but turned to Sir Geoff Palmer, a scientist and an anti-Dundas human rights activist, the outcome is hardly surprising. The danger of retain and explain, however, is not just the capacity for historical illiteracy. It is the very premise that it is necessary to expose some supposed moral flaw in those depicted in our statues.

The purpose of a statue is to celebrate someone in respect of specific public achievements. Churchill’s statue in Parliament Square is only there because he defeated European fascism. His character faults, or indeed the rest of his long and exceptional parliamentary career, are irrelevant. Statues have never been testaments of unblemished character, should such a thing exist.

If we are to get into the habit of writing statements of penitence in the name of context, almost no one from history would escape. For example, Haringey Council recently renamed Albert Road Recreation Ground in Muswell Hill after the anti–apartheid revolutionary Oliver Tambo, whose statue already stands in the park. Should there not be a plaque explaining that the African National Congress president authorised the Church Street bombing atrocity, which killed many innocent (black) civilians? Should it not memorialise the victims of uMkhonto we Sizwe’s practice of neck-lacing, whereby alleged collaborators with the apartheid regime had a car tyre forced over their head and arms, were drenched in petrol and then set ablaze?

I raise these questions not to doubt the legitimacy of the anti-apartheid struggle but to show how difficult it is for retain and explain to fulfil its purpose. We are asking too much of our civic monuments to educate us. Anyone who wishes to learn about slavery should go to a library or Elmina Castle. The base of a statue does not have space for a full historical account. At best, plaques restrict the life of the figure to a narrow frame. At worst, they deliberately mislead.

Britain’s curatorial class have convinced themselves that the public desires radical change. A survey in Leeds suggests otherwise. Of the 813 people (of a population of 792,525) who bothered to respond to the City Council’s statues review, 90 per cent wanted no action at all. Yet Historic England is all for retain and explain. The chairman, Sir Laurie Magnus, who has a touch of Sir Desmond Glazebrook, repeats the mantra on every platform.

I suspect many of our public servants are simply guided by the fear of being accused of defending the indefensible: namely that one supports slavery or racism. I suppose if you are a director or trustee of an older generation, particularly a white male, you must feel like Indiana Jones with the walls closing in. Your own staff might wish to see you squished. Tacitus’s ‘without anger or zeal’ approach to history is old hat. Likewise is custodianship in the age of ‘audience management’. The culture industry now resembles a political lobby group.

If you think I am overstating the case, look at the museums. Glasgow’s Hunterian has employed an incredibly titled ‘Curator of Discomfort’. London’s Natural History Museum claims Darwin’s voyage on HMS Beaglewas a ‘colonialist scientific expedition’. The folk at Kew Gardens, who appear to have been inhaling their plants, are going to reword their display boards ‘to address any exploitative or racist legacies’. The Museums Association itself campaigns for social and climate justice.

Who is all this justice for? The Labour mayor of Bristol, Marvin Rees, has claimed material inequality led to the toppling of Edward Colston’s statue last year. I doubt that. To believe artefacts with colonial or slave trade associations reproduce violence today requires subjecting oneself to hours of bad scholarship or ‘workshops’. The poor do not have that privilege. Such are the luxuries of an elite mob. And if democracy has any real meaning, it is surely the ability of the majority to laugh at their foolish ideas. But now these fads permeate schools, universities, museums, galleries, civil service, councils; in short, every civic and cultural institution. The joke isn’t funny any more.

Dowden is a rare breed of culture secretary who wants institutions to consider their remit. His department is still drawing up the guidelines on retain and explain. A museum curator I spoke to — a member of its decolonisation working group and anti-racism taskforce — thinks the policy is a compromise that will satisfy nobody. So if Dowden would like to please the majority — and won’t ditch retain and explain — these guidelines should at the very least force institutions to follow an academically robust process to prevent curatorial independence being used as a cover for political activism. If not, taxpayer money should be withheld. Such conditions wouldn’t need legislation. Otherwise, retain and explain is doomed to be another Tory policy where to accommodate is to capitulate.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in