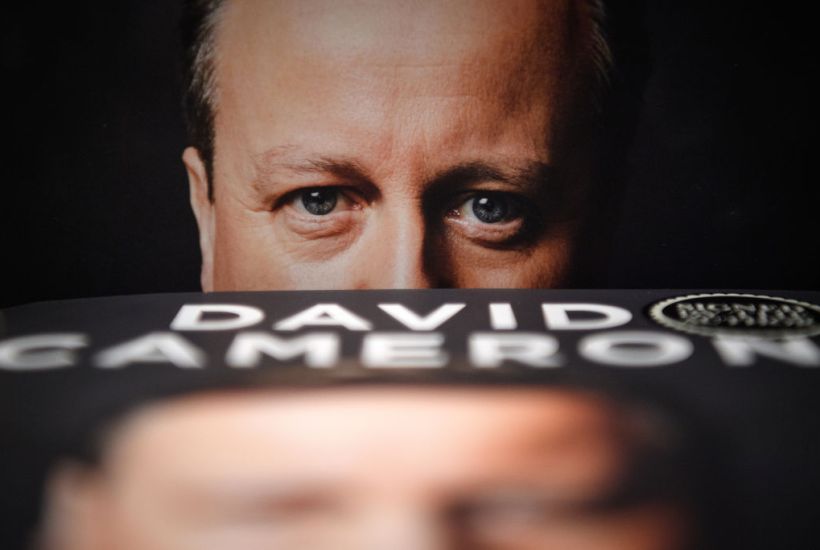

To paraphrase the old adage, truth can still be pulling on its boots when a misconception is already half way around the world. This is what has happened over the David Cameron/ Greensill affair. There is only one antidote to that: the facts. David Cameron’s statement sets these out clearly. There is to be an inquiry, which is likely to recommend procedural changes. It should also become clear that Cameron has nothing to fear from what has happened.

To see why, it’s first worth delving back to 2010, when the Tories had just returned to office. In the early days of the coalition government, there was much discussion about the future of the civil service. Francis Maude, the Cabinet Office minister, believed the system needed shaking up and that importing outsiders could help to bring this about.

A crucial figure agreed with him: Jeremy Heywood, the head of the civil service. The late Lord Heywood, who died tragically young at the age of 56, was one of the most respected civil servants of recent decades. Intellectually formidable, with as clear and incisive a mind as you were ever likely to encounter, he also had an easy and affable personality. This all gave him immense authority. Ministers were almost always ready to defer to him. Yet he was not always right.

On the civil service, it could be argued that the big problem had arisen in the Blair/Brown years. That government often seemed to want to turn the civil service into a glorified press office and was contemptuous of civil servants’ traditional skills.

These include caution. There is no harm in ensuring policy initiatives are rigorously thought through, so that the gremlins can be identified back in the policy shipyard, rather than after a launch into the rough seas of implementation. Able and self-confident ministers should welcome an element of creative tension in their relations with officials. One minister said that on some occasions, dealing with his permanent secretary was like trying to stuff newspaper through wire mesh. But that is the way to get things right.

The Blairites did not understand this. Buoyed up by a huge majority, they dismissed civil servants’ methods as just Sir Humphrey-style obfuscation. They preferred to legislate in haste, not realising that this could well mean repenting at leisure. When the inevitable difficulties arose, they often responded by blaming the very officials whose advice they had brushed aside. A bad workman blames his tools.

Jeremy Heywood was much better than all that, but he and Francis Maude were radicals. Perhaps they should have given the civil service more time to recover from the Blair/Brown sillinesses, so that its traditional strengths could reassert themselves. But they wanted to crack on with reform.

Heywood had spent some time away from Whitehall, working for a major bank, Morgan Stanley. One of his colleagues was Lex Greensill. Heywood found him to be impressive: a first-rate banker. Almost everyone would have concluded that if he passed Jeremy’s muster, he must have been very good indeed.

One of the issues which concerned Heywood was the supply of credit to small and medium enterprises (SMEs), who often hit cash-flow problems because their customers were slow in settling invoices. This was exacerbated by the banking crash of 2008/9. SMEs are a vital component of the British economy. For a range of reasons, principally technological change, large companies are unlikely to be net new employers of labour. So the UK is reliant on SMEs to create jobs.

In turn, SMEs cannot function without access to credit. Lex Greensill had been working on this throughout his career, which is why Heywood brought him into Whitehall. David Cameron was not involved in that decision and believes that while he was PM, he met Greensill no more than twice.

Was it appropriate for Greensill to have a 10 Downing Street business card, and who would have authorised it? The inquiry will no doubt consider that, but there is one obvious point. Lex Greensill had been brought in to get things done and a No. 10 card would have been an asset. The upcoming probe will presumably try to assess his efforts. But if he had not proved more than useful, it seems unlikely that his services would have been retained. Jeremy Heywood was likeable. He was also demanding.

Years later, after losing the EU referendum, David Cameron found himself in need of a new career when he was not yet 50. He took on a number of pro bono roles, dealing with Alzheimers, international development, seriously ill children, army veterans and national citizens’ service.

But he also wanted some commercial outlets. He could easily have picked up non-executive directorships – and even the odd chairmanship – of major City institutions. Bur he decided to be more adventurous. He was interested in futuristic areas, in particular bio-technology, artificial intelligence and financial technology (fintech). He was proud of the fact that, during his premiership, these had all been UK growth areas. He met Lex Greensill, was impressed by him and became a consultant, especially in relation to Greensill’s overseas activities. He was not a director and had no involvement in dealings with risk or credit.

On those areas, there seemed no grounds for anxiety. Greensill was heavily involved with Credit Suisse and General Atlantic. It dealt with a range of heavyweight companies, including Airbus, Ford, AstraZeneca and Vodafone. It seemed reasonable to suppose that Greensill’s operations had been scrutinised intensively by those responsible for due diligence.

Then came Covid. On the one hand, this made Greensill’s activities even more important. Up and down the land, thousands of SMEs had difficulties. Hundreds of thousands of jobs could have been at risk.

In March 2020, the Treasury set up the Covid corporate financing facility to bring succour to troubled businesses, as a matter of urgency. That urgency explains David Cameron’s decision to pick up the phone and talk directly to ministers. He now regrets that decision. His life would be easier if he had used more formal channels. But in those early pandemic days, it seemed reasonable to make haste.

At that stage, Cameron did not know the crisis was about to claim another victim. Greensill was over-extended. It had been insuring its bonds. Suddenly, that facility was withdrawn. Moreover, it provided financing to Sanjeev Gupta’s business empire: much more than he could repay. Cameron was not involved in that apparent failure of due diligence. Nor was anyone else sounding alarm bells.

Politics is a rough old trade. The Labour party cannot be blamed for setting its jackals in pursuit of a former Tory PM, nor for its wish to discredit Rishi Sunak. Keir Starmer and his team can recognise a dangerous foe. Labour MPs are happy to join in all this, because many of them instinctively believe that the City is riddled with malfeasance. Although they may pretend to be in favour of enterprise, in a large number of cases it is just that: pretence.

Cameron has one personal problem: an asset which sometimes becomes a liability. He is happy in his own skin. That was only true of a minority of modern PMs. In No. 10, it was an asset; he did not waste time agonising. But it can arouse resentment. Words like ‘entitlement’ are flung around.

In truth, David Cameron owes his successes to ability and hard work, resting on the secure foundation of a happy childhood. He does know how to enjoy life, but he has earned that right by his efforts, not by privilege. Yet a surprising number of people, including too many Tory MPs, are envious of tall poppies and like to snigger when they run into misfortune. That is really rather pathetic, especially from Tory MPs, who should know better.

David Cameron cannot wait for the inquiry. He will be happy to tell his story and answer all the questions. Why should he not be? He has done nothing wrong.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in