A year ago this week Alex Salmond was acquitted on all 13 charges in his sexual assault trial. In normal times the conclusion of the most significant political trial since the Thorpe affair in 1979 would have dominated the news for weeks. Instead, the story was overshadowed by the start of the UK’s first lockdown. But the aftershocks of this trial continue to rock politics in Scotland and beyond.

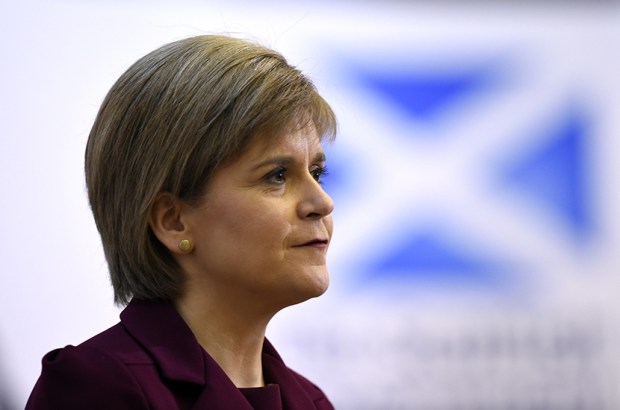

A Holyrood committee this week concluded that Nicola Sturgeon had misled it regarding her conversation with Salmond at her house about the Scottish government’s inquiry into him. The committee, which has a pro-independence majority but not an SNP one, decided this by majority vote. It was also sceptical of her claim that she had no suspicions about Salmond’s behaviour before November 2017. But a separate inquiry by the former Irish director of public prosecutions James Hamilton cleared Sturgeon of breaking the Scottish ministerial code, which he is an independent adviser on. Nonetheless, it is hard to work out what he thinks actually happened. As he writes, the redactions to his report mean that it ‘presents an incomplete and even at times misleading version of what happened’.

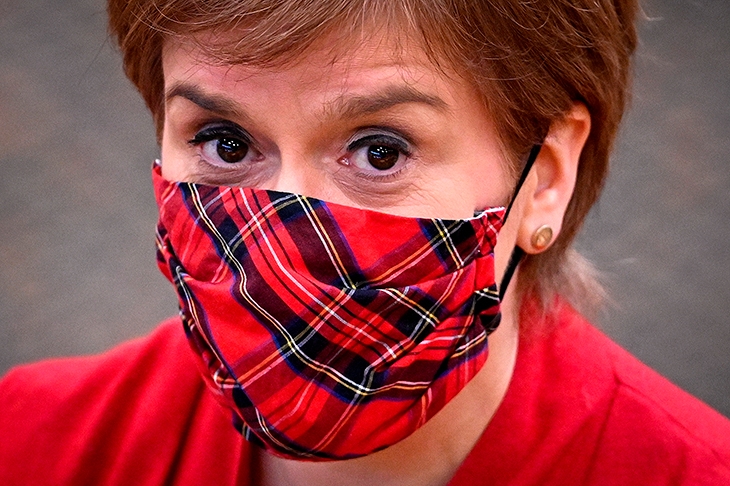

Understandably, Sturgeon is claiming vindication. The look of exhaustion etched on her face for weeks has been replaced with a smile. Unionists in both London and Edinburgh have been taken aback by how decisively Hamilton stated that Sturgeon had not broken the code. One MSP tells me that ‘people were shocked and stunned when the Hamilton report dropped’. In the Scottish Tory group at Holyrood, there is a sense that they got too far forward on their skis, that they shouldn’t have called for a vote of no confidence in Sturgeon before they knew the report and committee conclusions.

It would be wrong, though, to conclude that nothing has changed for the SNP. As one Unionist puts it: ‘She isn’t anything like as badly damaged as if Hamilton had even equivocated. But she is damaged.’ This whole business has drawn attention to how the SNP governs, and what it has revealed is disturbing. There is no getting around the fact that the Scottish government hasn’t taken responsibility for not only losing a judicial review to the former first minister at great expense to the taxpayer, but also for behaving in such a way as to cause ‘extreme professional embarrassment’ to the counsel it employed. On top of this, the initial two complainants have been deeply let down.

The tensions between the Salmondites and Sturgeonites over the past few months have made Sturgeon feel obliged to please her party’s base, who itch for a new referendum. The SNP now says it would hold a vote even if Westminster wouldn’t consent to it. It is very hard to see how such a referendum could be legal. The SNP has published a bill for an independence referendum in the first half of the next Scottish parliament. Polling for the think tank Onward shows that more voters want a referendum after 2027 — or never — than in the next two years. Voters feel that Scotland’s recovery from the pandemic should come first.

It is absurd to suggest that the after-effects of this virus will have been dealt with by November 2023. Two-thirds of disadvantaged pupils in Scotland were unable to do any schoolwork during lockdown. On the Scottish government’s own eight key diagnostics tests, the NHS waiting list is now more than 100,000 patients long, while the justice committee at Holyrood warns it could take a decade to clear the backlog in the courts. In the circumstances, the SNP’s demand for another referendum in the next two and a half years shows the party’s warped priorities. It also enables the UK government to reject the demand on the grounds that now is not the time.

Whether the SNP will have the votes for its referendum bill depends on May’s Holyrood elections, which are particularly unpredictable. Covid has made it far harder for politicians to read the public’s mood in the ways they normally do. Voter turnout is also very uncertain. This election will take place when many Covid restrictions are still in place – will people bother to go to the polls, even if the result clearly matters?

The Tories and the SNP will make much of their respective positions on indyref2 in a bid to energise their supporters. Since 2014, this dynamic hasn’t left much room for Scottish Labour. The party couldn’t find a way to cut through while the constitutional debate dominated. But under its new leader, Anas Sarwar, this might be beginning to change. Sarwar whipped his MSPs to abstain in Tuesday’s no-confidence vote and attacked both the Tories and the SNP for ramping up divisions, saying Scotland deserved both a better government and opposition.

There are some signs that this approach might work. It could appeal to those who are fed up with how the independence question keeps crowding out all other issues: 61 per cent of Scottish voters think the focus on the constitution has distracted politicians from concentrating on public services. Sturgeon has said she wants to be judged on closing the attainment gap between rich and poor pupils. Given that her party has made only minimal progress on the issue, it is hard to argue that the voters have got this wrong.

The TV debates will be particularly important in the election given how restricted other campaign efforts have to be during Covid. Sturgeon and the new Tory leader Douglas Ross are bound to go at each other, hammering away on the constitutional question. This gives Sarwar a chance to copy the trick that Nick Clegg pulled off in the 2010 general election, using his airtime to introduce himself to voters as a reasonable, moderate voice.

At the end of last year, an SNP majority looked so likely that some Unionists were urging the government to start work on a UK-wide Royal Commission on the constitution, so it couldn’t be dismissed as a panicked response to an SNP landslide. Now things are far less certain. Even if Sturgeon does win a pro-independence majority — perhaps propped up by the Scottish Greens — her haste to hold a referendum makes separation less likely.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in