Is Britain a nation? If you’re trying to maintain the United Kingdom — or destroy it for that matter — this is surely a very important question. It may seem obvious at first, of course the United Kingdom is a nation. Yet Unionists too often seem reluctant to address the question.

Devolutionaries, often non-separatist nationalists, are keen to talk about Britain as if it were merely an arrangement between states — like some kind of federal ‘United Kingdoms’ plural, rather than a singular polity made up of constituent parts. Full blown nationalists tend to reject the idea of British nationhood out of hand as it invites the awkward prospect of nationality as an overlapping and complex phenomenon that doesn’t magically confer a special legitimacy on their preferred group.

Even the government often seems reluctant to use the word ‘British’, favouring instead the sterile and technical ‘UK’ or the confederal language of the ‘four nations’. The politician’s instinct to focus exclusively on meeting wavering swing voters where they are is understandable. But to reduce the Union to a question of balance sheets — let alone to describe the UK as ‘a means, not an end’ — is to blunder into a nationalist trap.

Britain needs to be talked about and seen as a legitimate political and cultural — that is to say, national — community for the United Kingdom to work. It is only if ‘the British’ are a legitimate decision-making body that we can justify being governed as such.

Of course, many devocrats are not shy about wanting to replace British governance with intra-Home Nations horse-trading, or ‘shared rule’. But even as they plot the dismantling of British institutions, such people continue to base their case on the continued existence of something calling itself the ‘British taxpayer’, prepared to stump up for fiscal transfers across the UK.

If Britishness disappears, political consent for the ‘pooling and sharing’ of money will follow soon after. Pro-independence commentators such as the Herald’s Iain Macwhirter have freely acknowledged this, and talk about what a post-redistribution Union might look like. Labour’s devolutionary die-hards, such as Carwyn Jones and Gordon Brown, obviously can’t.

Fortunately, and despite the confused messaging about ‘four nations’, elements of the government seem to have clocked that the British state needs a national character. The underlying logic of the UK Internal Market Act is that the government can and will act directly to deliver for every part of the country, rather than allowing the devolved ministries to act as gatekeepers and treat its ministers as visiting dignitaries.

Like any effort to stray from the well-worn path of ‘ever looser Union’, they have been strongly criticised for this. Writing in the Guardian, Professor Michael Keating goes so far as to say the government’s efforts to protect the Union are ‘doomed’ unless it ‘stops conflating unionism and nationalism’.

The problem is that it isn’t obvious what Keating thinks the basis of Britishness should be. He rightly scorns specious attempts to root it in ‘values’, which are invariably simply a list of nice things which do nothing to distinguish the British from our neighbours in other Western democracies. He correctly identifies how Britishness was traditionally anchored in loyalty to institutions, but doesn’t follow this thought to its obvious, somewhat devosceptic conclusion.

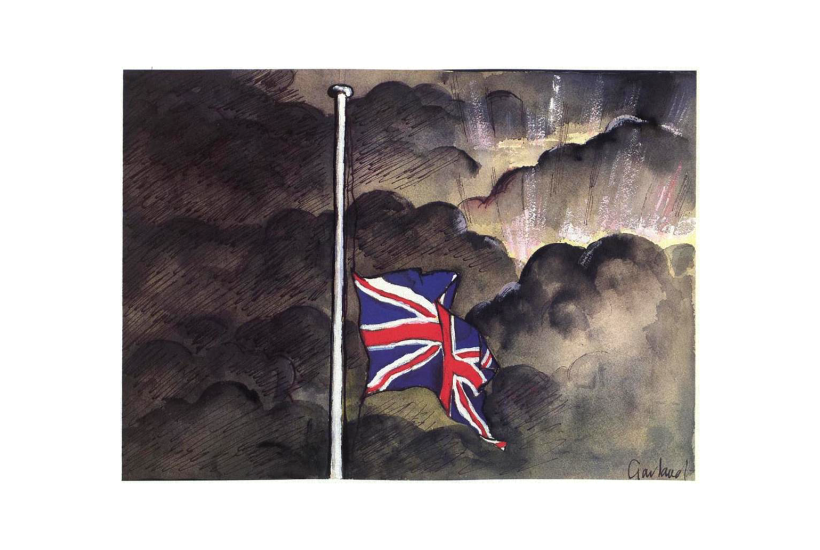

In fact, for all that some sneer at the government’s enthusiasm for the flag, we should not be at all surprised that the British are becoming more assertive about their identity in the age of devolution. ‘Why isn’t Unionism as relaxed about symbols as it was when Britain was politically unitary and the separatist parties wholly marginalised?’ is a very silly question, for all the learned analysis that seems to rest on it. If traditional Unionism was a ‘balance’ between identities, that balance needs to be maintained — and that requires movement in both directions, or none. This also helps to explain the rise of devoscepticism. For two decades, the debate on devolution has been framed by its advocates as being exclusively about means, whilst what was meant by the supposed common aim of ‘saving the UK’ was left unexamined. After two decades of retreat, and with no end in sight, the re-emergence of devoscepticism reflects a growing number of unionists deciding that they’re in the fight for more than just the technical existence of a threadbare confederation calling itself the United Kingdom.

But the failure of devolution to ‘kill the nationalists stone dead’, as the incoming New Labour Scotland secretary said it would in 1997, has made this unsustainable. Someone who is content to see the UK shrivel to a defence and diplomatic community, or is just in it for the fiscal transfers, is manifestly not fighting for the same thing as someone for whom the British state is their national state. And even if British identity is much weaker now than in decades past, there are still millions of us.

At the very least, even if one rejects on dogmatic grounds the idea of multi-levelled nationhood, the British are the United Kingdom’s fifth nation. Too many people mark themselves as just ‘British’ on the census for it to be anything else. They are right to reject the false dichotomy between devolved ‘self-rule’ and reserved ‘shared rule’ — parliament is the forum for British ‘self-rule’.

And that’s before we count the enduring outposts of the British nation overseas. Fabian Picardo, the First Minister of Gibraltar, spoke this month about how the Rock had benefited from being part of ‘the British family of nations’. The government has taken decisive action to offer a pathway to citizenship for millions of Hong Kongers, who protested for their traditional freedoms under the Union flag. (I’m proud to support Global Britons, the campaign to deliver the same rights for other so-called ‘residual nationals’.) For nearly a century, hundreds of thousands of colonial subjects — coming from India, Africa or the West Indies — arrived on these shores with an identity that included, in some sense, Britishness.

Nation-building is a complex, long-term project. There will be no tidy ‘big bang’ solutions, and government strategists are almost certainly right that they wouldn’t be able to dig deep new reservoirs of national feeling in time to fight a referendum on such terms in the next few years.

But it remains essential to securing a long-term future for the United Kingdom, which needs Britons just as much as the EU needs ‘Europeans’ if integration is to stick. All the more reason to stand firm, refuse a second vote, and buy the time such a strategy demands.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in