‘Ah, did you once see Shelley plain?’ asks the speaker in Robert Browning’s poem ‘Memorabilia’ — a line which recognises how easy it is to misread a writer once they’ve passed into a hazy afterlife of fame, neglect or simple misunderstanding. Yet few of Browning’s contemporaries are as hard to see plain as his own wife: the poet who was known to her family as Ba, signed herself EBB, and published a number of popular works under her married name of Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

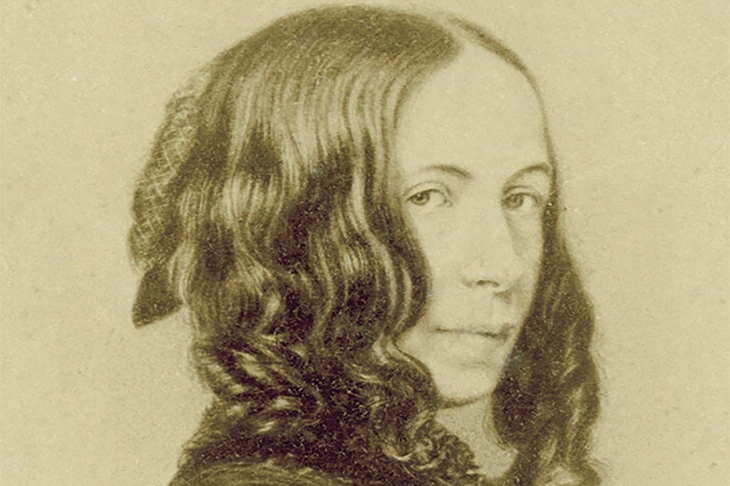

During her lifetime she was one of the most admired poets of the age; a framed portrait of her hung in the bedroom of Emily Dickinson, and when Wordsworth died in 1850 there was serious talk of her becoming the first female poet laureate. Since her death in 1861, however, her reputation has sunk like a bad soufflé.

For many readers, knowledge of her poetry is now restricted to a single line reproduced every year on thousands of Valentine’s Day cards — ‘How do I love thee? Let me count the ways’ — while her lifelong struggles with illness and laudanum addiction have been replaced in the popular imagination by sugary romances such as Rudolf Besier’s 1930 play The Barretts of Wimpole Street and its 1964 musical adaptation Robert and Elizabeth.

Even the Google Doodle that celebrated her birthday in 2014 turned her into a girlish figure who appeared to be oddly fascinated by a wilting flower. Tiny in real life (Annie Thackeray described her as ‘very very small, not more than four feet eight inches I should think’), in death she has been treated more like a wax doll: a pretty simulacrum of a human being without any inner life at all.

There were some early warning signs in Virginia Woolf’s 1933 novel Flush, a playful version of Elizabeth Barrett’s life as seen from the perspective of her pet spaniel. In one scene Flush barks and trembles at his own reflection in a mirror: ‘Was not the little brown dog opposite himself?’ asks Woolf. ‘But what is “oneself”? Is it the thing people see? Or is it the thing one is?’ The central aim of Fiona Sampson’s new biography is to strip away the illusions we have about this unfashionable poet and get far closer to seeing her as she was. It is a bold attempt to understand EBB before her reputation started to ebb.

She was born in 1806, and her early life was in many ways a pastoral idyll. Growing up in a large country house in Herefordshire that was (to her considerable embarrassment as an adult) paid for by her family’s involvement in the slave trade, as a child she was encouraged to write poetry that made up in confidence for what it lacked in skill. (An ode on her sister Henrietta includes the lines: ‘But now you have a horrid cold, /And in an ugly night cap you are rolled.’) She was also a tomboy who boasted that she ‘could run rapidly & leap high’and ‘climb pretty well up trees’.

Then it all started to go wrong. By the time she was in her twenties, a long list of symptoms that included intense physical pain, crippling fatigue and bronchial infections that caused her to cough up what Sampson refers to as ‘slugs of yellow, grey, green mucus’, meant that she spent most days confined to her bedroom and a ‘little slip of sitting room’ on the third floor of 50 Wimpole Street, the family’s new London home. Here she was protected from the outside world by a fiercely loving and gloomily religious father, who refused to countenance the possibility that she might ever want to leave him for another man. It was like living in a nunnery of one.

Her main form of escape came through the poetry she continued to write, including heart-tugging appeals such as ‘The Cry of the Children’ (1842), which helped to publicise Lord Shaftesbury’s reform of the child labour laws, and a bestselling two-volume collection of Poems (1844). For someone whose life was usually enclosed by four walls, poems were like an extra set of windows she could open onto the world.

They were also far less willing to submit to the sort of limitations she had to settle for in her own life. A poem such as her semi-autobiographical epic Aurora Leigh (1856) is written in a form of blank verse that keeps fraying at the edges and sometimes gleefully bursts apart at the seams. Repeatedly the speaker’s voice reveals itself to be much more disruptive than it might at first appear: not that of an angel in the house, but rather of a woman who wants to show us how hard it is to move around while wearing a crinoline without bumping into the furniture.

The turning point of Elizabeth Barrett’s life was her first meeting with the man who would become her husband. Even before they saw each other it was clear how much they had in common. Robert Browning’s earliest communication with her in 1844 was a fan letter that he signed off: ‘I do, as I say, love these books with all my heart —and I love you too.’ And as their relationship blossomed over the next few months both of them enjoyed tangling together writing and real life.

Not only did they meet frequently in person — Robert would end up making 91 visits to Wimpole Street in total — they also wrote to each other almost daily, lovingly playing around with each other’s choice of language in a series of intimate allusions and private jokes. In effect they were practising for the time when their hands would be joined together more permanently in marriage. Each time one of Elizabeth’s letters left her bed-sitting room to make its way across London it was like a literary exercise in elopement.

After a secret marriage and rapid departure from Wimpole Street in 1846, their final destination was Italy, where they moved into a seven-roomed apartment in the Palazzo Guidi in Florence. Sampson is especially good on the happy routines of their life, as they spent their days eating ice cream, entertaining visitors, and writing, writing, writing.

Following this honeymoon period and the birth of a son, whom they jokingly nicknamed Pen, they seem to have drifted apart in terms of their daily activities. After disagreeing over matters such as spiritualism (Elizabeth was intrigued and hopeful, whereas Robert dismissed it as an absurd hoax), Sampson reports that within a few years they were ‘leading almost parallel lives’. Yet they remained as close as ever on paper. There is something painfully moving in Robert’s report of his wife’s last illness, as he lifted her up towards him and she kissed him repeatedly, even kissing the air after he had laid her back on the bed, and murmuring ‘Beautiful… beautiful’ as she held out her hands to him one last time. When she died he was broken by grief. ‘How she looks now,’ he wrote from her deathbed, ‘how perfectly beautiful.’

Sampson points out that in some ways these final moments were just the most literal version of a struggle that Elizabeth had always experienced as a female poet, forever ‘fighting for breath, determined to stay alive and to speak’, and this biography is a generous attempt to restore her reputation. The individual who emerges is not the sad-eyed invalid we are familiar with, but an ambitious woman who enjoyed teasing men. One letter to Robert during their courtship breaks off with an ellipsis that is also a saucy come-on, telling him that she longs ‘for some experience of life & man, for some…’) She could also be surprisingly catty. ‘I never could apprehend that a person with such breadth of chest & with so little tendency to becoming thin, was of a consumptive habit,’ she once observed of a friend’s daughter.

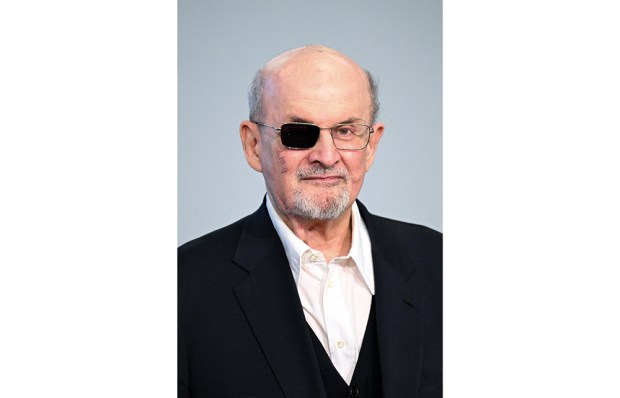

Occasionally Sampson’s attempts to turn her into a more contemporary figure strike a false note, with references to ‘virtue-signalling’ and ‘snowflakes’ that are themselves likely to sound outdated before too long. But, overall, this is a fine contribution to

a growing number of biographies that try to pick off the barnacles of rumour and legend that have attached themselves to the lives of writers, and instead reveal them as they really were — or at least how they appear to us now.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in