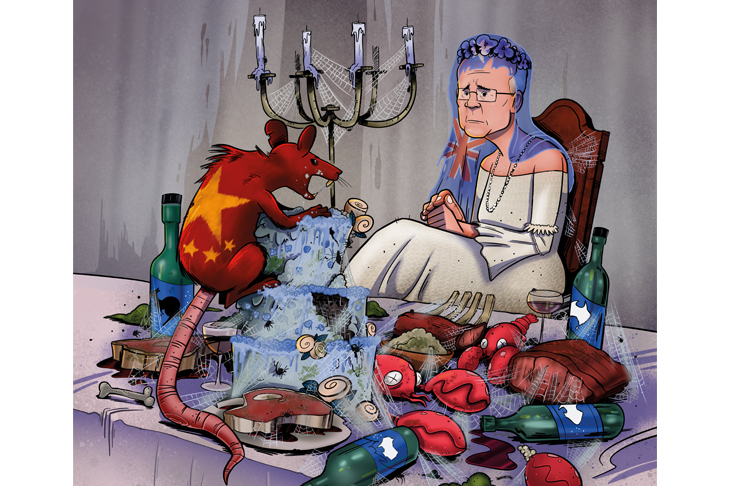

China’s wolf warrior diplomats keep warning us to ‘reflect on our deeds’ or learn how it feels to ‘walk into the dark’. Beijing’s hostility towards Australia has taken us by surprise and not just for the obvious economic reasons. We are, for the most part, a pragmatic people who long ago adopted a live-and-let-live attitude to the rest of the world, not least the People’s Republic of China.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in