‘From this evening, I must give the British people a very simple instruction — you must stay at home,’ Boris Johnson declared on 23 March. At the beginning of the pandemic, when infection levels first began to rise, the country was all in it together. The prescription was a national one, and the Prime Minister could speak to the nation as one. Though infection levels have begun to surge again, the restrictions are now specific and local. The PM can no longer address the country as a whole, and this poses a problem for him.

Last time, at least, there could be no claims that the Tories were favouring one particular area at the expense of the rest. When London was hit hard and the South-West virtually unaffected, everyone was given (and obeyed) the same stay-at-home mandate. Cabinet ministers admit that one of the reasons a London-only lockdown was ruled out then was a fear that it would send out a message that life in the capital was more valuable than elsewhere.

Now, Scotland and Wales are doing things their way — Nicola Sturgeon is perhaps about to impose the strictest rules in the UK. Two-thirds of the north of England is under heightened restrictions, and has been for weeks. But in the south of the country, life carries on close to normal. This is a gift for those politicians whose stock-in-trade is arguing that ‘Westminster’ doesn’t care about them, and it makes the policy response harder too: what national economic support should be available when parts of the country are functioning fairly normally and other places are under intense restrictions?

The government’s plan so far has been to introduce a system of Covid alert levels, corresponding to three levels of restrictions. But the announcement of this scheme is being held up by two questions. First: what should the thresholds for the various restrictions be? Next: how strict they should be? Once that has been decided, I’m told, the government wants to see into which category every region would fall before announcing the policy.

The danger is obvious: any scheme like this will end up looking like a plan to lock up the North. Just as the South was hit hardest by the first wave, the North is bearing the brunt of the second. Look at the new Covid hospital admissions on 4 October: 334 in the North and Yorkshire, ten times that of the South. In London, just 27. And yes, local lockdowns would be a move to save lives in the North — but restrictions are harmful too, and they exacerbate the very north-south divide that the Prime Minister wants to see an end to.

It is not hard to see how a divided Britain translates into political tensions. Labour and northern leaders would claim that the support packages would be more generous — and the situation better handled — if it was the South that was bearing the brunt. ‘It’ll be like flooding,’ warns one cabinet minister. ‘People will say: they’d take it more seriously if it was happening in Surrey.’

There is a Tory worry that this situation could provide Labour with a wedge to drive between Johnson and his new northern supporters. If Keir Starmer can persuade the North that it has been betrayed by the Conservatives and should come back to the Labour fold, then the Tory majority vanishes. Andy Burnham, mayor of Greater Manchester — and a Liverpudlian — has long argued that ‘Westminster has failed the North’ and has developed this theme in recent weeks. You can already hear talk that Tories are happy to incarcerate the North with little additional financial support because life is continuing as normal in the South. One minister complains that the accusation ‘is nasty, sly politics — but it has a resonance’.

One of the problems is that, as Burnham puts it, these restrictions seem like Hotel California: once an area is in lockdown, it never leaves. Another is that the government has been very vague about what pushes an area into lockdown. One of the reasons for this is that the government is responding to a constantly changing situation. As a Secretary of State puts it: ‘Whatever we may wish, we end up having to make it up as we go along.’ This risks creating the politically toxic charge that the Tories are experimenting on the North to try to find out what works; it triggers the folk memory in Scotland that Margaret Thatcher used the country to experiment with the poll tax like some wicked scientist before introducing it in England.

One figure in government says that the way the virus is circulating means that it is inevitable the North will be subject to more restrictions than, say, the South-West, but warns: ‘You need independent criteria from the JBC [Joint Biosecurity Centre] which recommends things. That would be much better than ministers sitting in a room and making decisions.’ As this source puts it: ‘Clarity would get rid of the idea that different judgments are being applied to different places.’

But such clarity could be elusive. Health Secretary Matt Hancock is in favour of greater transparency but even he doesn’t favour a simple set of clear criteria, and as long as ministers are deciding which places are subject to what restrictions, there’ll be accusations of favouritism. Even if the process is not political, it will look as if it is.

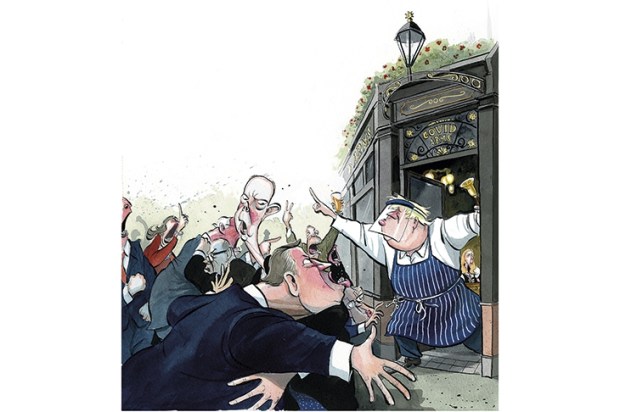

Another tension is over how far the restrictions should go in the worst-affected areas. The private view of the Department of Health is that local lockdowns are failing because they aren’t tough enough. With the number of cases spiking in Liverpool and Manchester — and hospital admissions in the North-West back at April levels — the Department of Health want pubs and restaurants closed in the worst-hit places. But the Treasury and the other economic departments worry about how many businesses that would send to the wall — and how many people it would leave unemployed, with all the attendant physical and mental health problems that brings.

It isn’t just within England that things now vary. Nicola Sturgeon’s SNP government have very consciously chosen to take a different path when it comes to the virus. They chose to come out of lockdown more slowly, to enforce mask-wearing earlier and generally take a more precautionary approach. Some of Sturgeon’s advisers described this as a push for a ‘zero Covid’ Scotland. In June, Sturgeon herself said that her stricter approach had left Scotland ‘not far away’ from eliminating the virus. Now, Glasgow is recording one of the highest infection rates in Europe.

Sturgeon has been aided by the Westminster government’s failure to understand how much is devolved. For instance, No. 10 believed quarantining arrivals from abroad would be UK-wide. But because it was being done under public health regulations, the rules in the four parts of the UK differed: at one stage, returnees from Portugal had to quarantine if they flew into Cardiff, but not London City Airport. For those with a political interest in the disaggregation of the United Kingdom, these tensions also serve a political purpose. ‘The SNP are seizing the opportunity to make a very clear and distinctive point about borders,’ warns one cabinet minister.

For all these reasons, the Prime Minister is keen to keep as much as much of a UK-wide approach going as possible. Officials from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are now all invited to a weekly meeting of the cabinet’s Covid Operations committee and there’ll be a summit with them to discuss winter preparedness.

One other area of tension is the Welsh government’s desire to refuse entry to people from Covid hotspots such as Manchester or Liverpool. Johnson has rejected the idea, but if the Welsh continue pushing, the UK government might feel obliged to let them have their way. One of those involved in government discussions on the matter tells me that there is concern about what continuing to reject this request might mean. I’m told that in Whitehall there’s ‘real fear about what such a move would do to the nationalist movement in Wales and Scotland’. So the UK is pulled all directions.

A frequent Westminster complaint is that the devolved administrations don’t have to balance health and the economy in the way that the UK government does because almost all taxes are collected (and money borrowed) nationally. One of those intimately involved in the UK Covid response laments that the devolveds ‘have a particular interest in locking down as they don’t pay the bills’. This is going to become a particularly acute problem as the furlough scheme comes to an end. There is going to have to be some support put in place for those businesses, and their employees, that are closed again in any local lockdowns. The risk is that Sturgeon takes a much more precautionary approach, shutting far more places, and then has firms and their workers sending in requests to the Treasury for help.

Arlene Foster, the Northern Ireland First Minister, has a solution to this problem. In discussions, she has suggested that the four nations agree on a threshold of cases per 100,000 at which UK support would kick in. This wouldn’t stop the devolved administrations from applying more stringent restrictions, but it would mean that if they did, it wouldn’t be the Treasury who would end up picking the bill. Meanwhile Burnham is arguing for more financial support for northerners facing restrictions — absence of such support, he says, will be a double whammy. ‘We are being levelled down, not up,’ he complained recently. ‘This can’t continue, because if it does it will make the recovery so much harder in Greater Manchester.’

Johnson’s election victory in December was based on persuading voters in the ‘red wall’ both that his party were not ‘the same old Tories’ and that Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour was not the party that their grandparents voted for. The danger for the Prime Minister is that long months of restrictions across the North — while life and economic recovery goes on almost as normal in the South — might make his new friends think that the Tories really haven’t changed that much after all.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

spectator.co.uk/podcast - James Forsyth and Middlesbrough mayor Andy Preston on the Covid divide.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in