There’s a reason why No. 10 is always so inclined to ratchet up the tension in any given scenario. Downing Street’s staff, and particularly the Vote Leave alumni, believe that one of their strengths is that in high-pressure situations, they stay calm while others panic. This confidence is not totally misplaced. Last autumn, Boris Johnson and his aides kept their nerve better than any other group in British politics — the result was a decisive parliamentary majority. Last October, they suggested Brexit talks were over and no deal was inevitable. They then briefed out unprecedented levels of detail from a Boris Johnson-Angela Merkel phone call before eventually doing a deal.

Critics claim that the withdrawal agreement they struck was always available, but this misses something important. The tactics ensured that the arrangements in Northern Ireland can only be renewed with the consent of Stormont, which made the agreement far more acceptable in democratic terms. In Westminster, they kept pushing for a general election until the opposition parties cracked and gave it to them. Others would have reconsidered after they failed in their first three attempts. But they simply pressed on, ramping up the rhetoric each time.

Now No. 10 is raising the stakes again. Last Thursday, the European Council’s conclusions said that all the concessions to get a deal would need to come from the UK and refused to commit to intensifying the negotiations. This statement almost seemed designed to rub Britain’s nose in it. No. 10 responded saying the trade talks were over unless the EU changed its position. The Council conclusions were particularly ill-timed as they coincided with Johnson being (in the words of one of those who knows him well) ‘emotionally attracted to Australia again’. Australia is Downing Street’s term for trading with the EU largely on WTO terms.

On Monday, Michel Barnier offered an olive branch. He said the EU was prepared to discuss legal text. Soon after this became public, one secretary of state told me that David Frost, Britain’s chief negotiator, ‘has been wanting to share legal text for ages’. Given that the government has legal text ready, it looked like this would be enough to get talks going again. But No. 10 said no. They wanted a change on substance, not just process, and for the EU to row back publicly from the Council’s conclusion that all the compromises would have to come from the UK.

That is a reasonable request. The more pragmatic players on the EU side realised soon after the conclusions had been issued that there had been a miscalculation. One of these is Barnier, who talked at the press conference of ‘intensifying’ the talks. Angela Merkel emphasised that both sides would need to compromise and Micheál Martin, the Taoiseach, stressed that in discussions later on in the summit EU leaders had given Barnier the flexibility he would need to strike a deal. Interestingly, when Oliver Lewis — David Frost’s deputy — spoke to the One Nation Group of Tory MPs on Monday night, he was quite warm about Barnier and blamed the impasse on certain national EU leaders.

It’s possible for talks to resume. All it would take is someone from the Commission to say to the government — as Merkel did in her press conference — that both sides will need to give some ground. That would satisfy Downing Street. The idea that all the concessions in a negotiation have to come from one side is positively Carthaginian and simply not serious. One wonders if this over-the-top stance would have been adopted if Ursula von der Leyen, the Commission President, had not had to leave the summit because someone in her outer office tested positive for Covid. She had spoken to Johnson on the eve of the summit, and would have been more aware than most how these conclusions were likely to play in London.

Barnier and Frost spoke again on Tuesday. On Wednesday morning, Barnier struck a conciliatory tone in the European Parliament, talking about the need for ‘necessary compromises on both sides’. This has certainly improved the mood, but at the time of writing there is no word yet on whether proper negotiations will resume. We shouldn’t be surprised at No. 10’s attitude, though. Johnson is determined to show that he is not desperate for an agreement. As one senior figure at No. 10 likes to say: ‘The first rule of getting a deal is not wanting a deal.’ Or to be more precise, not looking like you want a deal.

It’s a high-risk strategy. To leave without a deal would bring a level of disruption that would further threaten the government’s reputation for competence and would inevitably mean lots more negotiations with the EU at a later date. The difficulty at the borders — from traffic jams onwards — would be perceived as leverage for any future negotiation. There are those in Paris who believe that a no-deal Brexit (and a strict approach to customs checks) would send the Brits running back to the negotiating table, eager to compromise. But this is a misreading of No. 10’s position, which is that if Britain goes for no deal, it must ride out any disruption and wait for the EU to make the first move.

Such a standoff could last for months — right up to the Holyrood, Welsh assembly and English local government elections in May. These votes are particularly important as the government’s first post-Covid electoral test. The SNP may well win an outright majority at Holyrood, and there is nothing that would suit their campaign agenda more than a chaotic no-deal Brexit. Nicola Sturgeon will then make a request for a second independence referendum. If her majority is large, it will be harder for the government to just say no.

The Prime Minister’s appetite for risk is greater than most of his cabinet ministers, who are (including some surprising people) very much in deal mode. If Johnson brought back a Brexit deal, his cabinet would be relieved, rather than nervous about what had been conceded. Johnson often declares that ‘I’m the toughest member of the cabinet’ when it comes to Brexit. This is true. No one around that table is more prepared to take the risk of leaving without a trade deal.

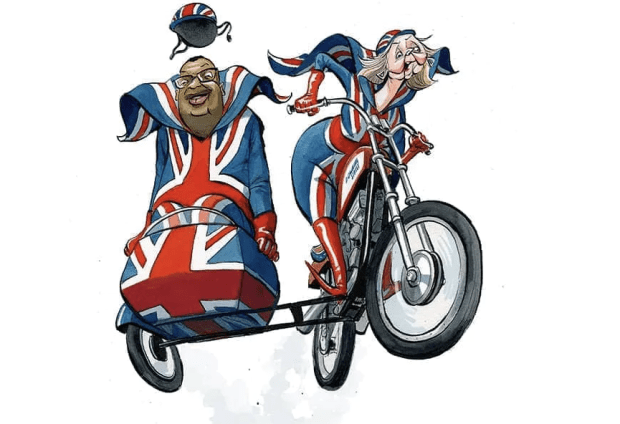

One of those close to the negotiations still believes that an agreement is more likely than not. But the tactics make it very unpredictable. Both sides are trying to pressure each other, leading to what one minister calls a ‘crazy game of chicken’. It’s very possible that one side will end up miscalculating. With just weeks left, it really could go either way.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in