Nothing courts us so nimbly as technology. Perhaps the chess computers have already won you over — I am dazzled by the riches they have revealed. For a jaw-dropping sense of wonder, try playing over a forced mate in 549 moves.

Still, many yearn for a simpler time. A time when the mysteries of chess were plentiful, but studying the game ‘by hand’ yielded steady nourishment. A time when chess engines had not yet tempted us with their very own tree of the knowledge of good and evil. These days, that tangle of variations and verdicts is irresistible, but who can look at their own play without a sense of shame? Meanwhile, professional players must work harder than ever to harvest fresh ideas. Alas, spectators are underwhelmed when the consensus of optimal moves in a well-worn opening boils down to a sterile equality.

What if we could tweak the rules slightly? Ideally, we preserve the game’s natural tension and depth, but subvert the most familiar patterns of play, so players are thrown on their wits from the first moves. This is delicate, as the rules of chess have been tuned over many centuries; it is hard to foresee whether changing them would unbalance the game. That is where technology promises us a path back to paradise.

DeepMind, the artificial intelligence company, released a paper last week: ‘Assessing Game Balance with AlphaZero: Exploring Alternative Rule Sets in Chess’. AlphaZero is the ground-breaking chess engine which reached superhuman levels by learning from games played against itself. That is the crucial feature which makes it suited to ‘exploring alternative rule sets’. The same algorithm, learning from the ground up, can be applied to any variant of chess. In a matter of hours, the researchers could generate countless high-quality games in their chosen variant, which could then be mined for insights. Is there scope for originality in the early stages? Are decisive games more frequent? Is it beautiful?

Former world champion Vladimir Kramnik’s name, alongside three DeepMind researchers (including CEO Demis Hassabis), lends the paper a unique authority. Kramnik has a deep sense of the game’s aesthetics, and was, before he retired, a prolific innovator in the opening phase. But in recent years, even he insisted that fresh ideas were hard to come by. Last year, he voiced his support for a variant identical to regular chess except that castling is no longer permitted. Since castling is a standard fixture of almost all openings, this makes for a huge shake-up in the early stages. With kings stranded in the middle, and rooks waiting in the wings, the game becomes considerably sharper.

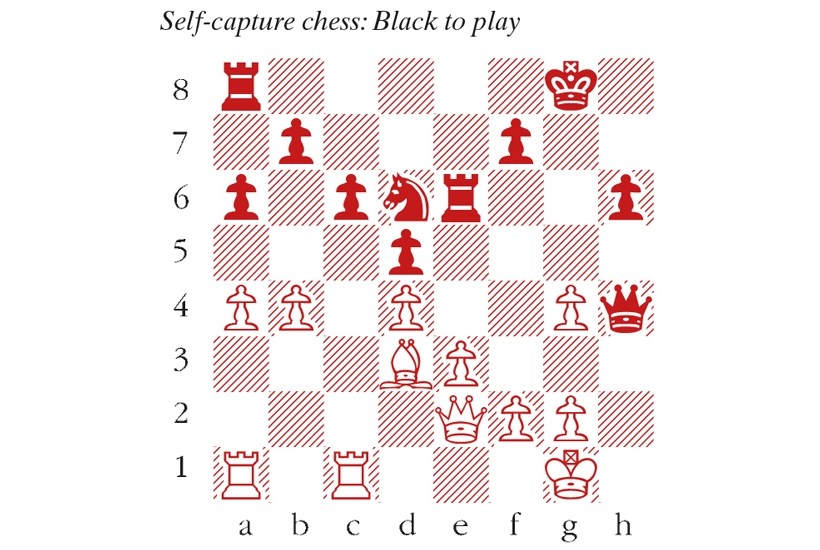

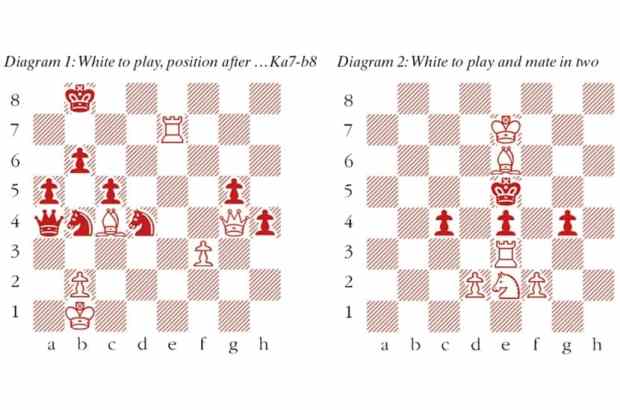

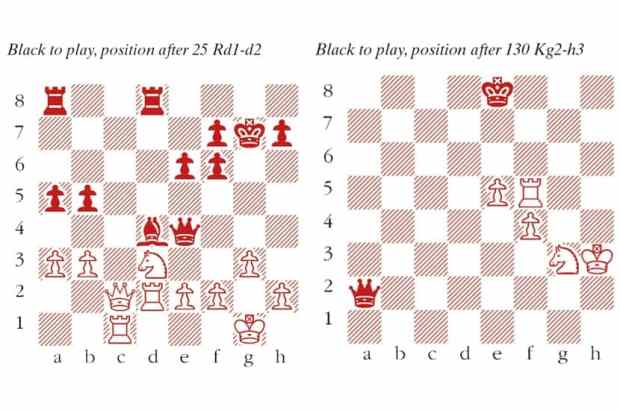

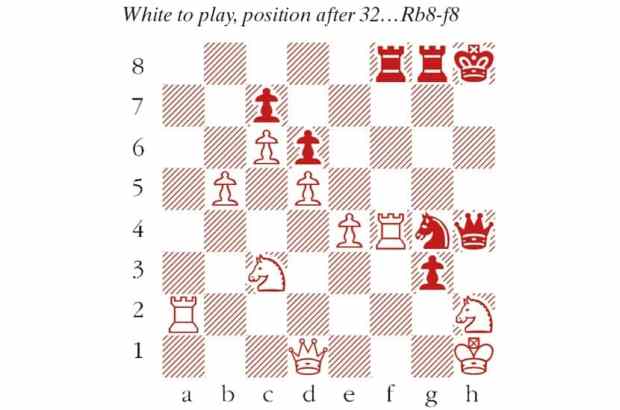

In ‘self-capture chess’ (another of nine intriguing variants examined by AlphaZero), players are permitted to capture their own pieces. In Kramnik’s words: ‘I would even go as far as to say that to me this is simply an improved version of regular chess’. That’s an extraordinary claim, particularly as the self-capture option means that many standard mating patterns no longer work. (For example, facing a smothered mate with a knight, the attacked king would just capture one of his obstructive comrades.) But new dynamic ideas arise in their place. In the endgame, advanced pawns can capture their own pieces to circumvent a blockade. Or take a look at the diagram, a sample self-capture game from the paper. If the pawn on h6 were absent, 1…Rh6 would be natural, threatening Qh4-h1 mate. In self-capture chess, the Black rook can capture its own pawn to play exactly that: 1…Rxh6! White blithely responded 2 Qf3, because after 2… Qh1+ comes another self-capture move 3 Kxf2! and the king slips away. The game continued 3…Qh4+ 4 Ke2 Re8 and ended in a draw after further adventures.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in