Boris Johnson is far from being the first prime minister to holiday in Scotland. David Cameron used to slip off the radar at his father-in-law’s estate on the Isle of Jura, and plenty of other Conservative premiers have enjoyed a Scottish August on the grouse moor. But Johnson may be the first to holiday north of the Tweed as a matter of political calculation and convenience. He comes to Scotland to show his commitment to what he calls the ‘magic’ of the Union.

About time too. At last — at long last, Scottish Unionists might say — the cabinet has recognised it has a problem in North Britain. Indeed, the problem is that fewer and fewer Scots believe they should be inhabitants of Britain at all; opinion polls suggest that if an independence referendum were held next month, Scotland would vote ‘yes’. The saving grace for Johnson is that there will be no such referendum this year or next.

In normal circumstances, next year’s Scottish parliament elections would be very challenging for Nicola Sturgeon and the SNP. The party has been in power for 13 years; long enough to exhaust voters’ patience. This week, Sturgeon’s government performed perhaps the greatest U-turn in the history of the Holyrood parliament, reversing course on the allocation of exam-substitute grades that saw thousands of pupils receive poorer results than predicted. Results that were last week deemed ‘credible’ if unfair are now, by Sturgeon’s own logic, fair but incredible.

Education, not independence, is notionally Sturgeon’s no. 1 priority. She has asked to be judged on her record, knowing full well that she will not be. Scotland has a five-party political system but one of these parties, the SNP, commands the loyalty of nearly 50 per cent of voters. Sturgeon could shed a fifth of her support and still dominate the political landscape.

Ostensibly, the practical arguments in favour of independence are weaker now than when the question was put to the Scottish people in 2014. Some oh-so-clever Tories suggested Brexit might put Scotland in a box from which there was no palatable escape, that the prospect of significant trade barriers between Scotland and England — to which more than half of all Scottish exports are sent — would make independence more daunting. But if Brexit can represent the triumph of sovereignty over economics — a respectable position — then so can Scottish independence. Separatism is a sensibility, rather than a fully costed set of detailed policies. It’s not the economy, stupid. Not any more.

Viewed from the pro-independence perspective, that is just as well — since the early years of the new Scottish nation would be much like the final years of the old, pre-1707, Scottish nation: damnably difficult. The SNP have not, as yet, formulated convincing answers on matters of finance, currency, and much else besides. In 2014, the nationalists claimed Scotland could have it all: more spending without the inconvenience of increased taxation. That was an illusion then and it is now an impossibility. Oil prices have more than halved.

The future will not be oil-powered, but it will be expensive. Scotland’s deficit, always far higher than the EU demands for new member states, will be even higher now.

But in the Union, there is no such thing as a Scottish deficit: if there is a gap between what Scotland spends and what it raises in tax, that is filled by HM Treasury. The argument that Covid-19 has underlined the extent to which Scotland benefits from the broad financial shoulders of the United Kingdom has not yet proved persuasive. It might be true, but it is simply not believed. It is also true that the SNP’s 2014 independence plans would have led to ruin — a central bank, as it turns out, is an important institution. But, as with Brexit, most independence supporters trust that in the end everything will turn out for the best. Unionists are slowly realising, to their horror, that it doesn’t matter how strong the maths is. The financial counter-arguments don’t work.

The catalyst — what has turned public opinion in Scotland into a small but fairly consistent majority for independence — is Covid. Sturgeon has performed well. Her public health responsibilities, plus the platform afforded by her daily press conferences, mean that she has been put on a near-equal footing with the Prime Minister and that has allowed direct comparisons. Where he has been a mess of conflicting messages, she has been measured and consistent. Scots have gained the impression that the quality of their government is just, well, better.

Viewed dispassionately, Scotland has not had a good coronavirus crisis. Although new infections are now running lower than the rate seen in England, overall Scotland’s excess death rate remains among the worst in the world. The steps taken in England — locking down later than other countries, shifting elderly patients from hospitals into care homes — were also taken in Scotland, at the same time. For much of this crisis, the differences between Edinburgh and London have been of style not substance.

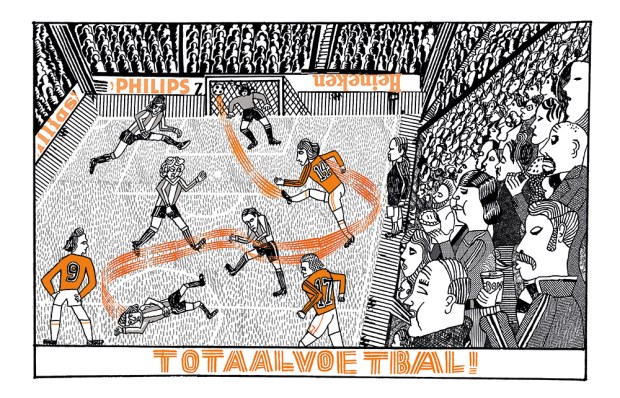

But politics, like football, is local. In the national football team’s happier days, it was nice when Scotland defeated France or Spain but beating England really mattered. As at Hampden or Wembley, so now at Holyrood and Westminster: success is not measured in absolute terms but is relative to whatever is happening in England. Hence this curiosity: the Scottish nationalist movement tirelessly congratulates itself on doing just a little bit better than a place it sees as not very much better than a failed state. One day, perhaps, Scots will be more ambitious than that.

Just over three in five Scots voted against Brexit, and the fact that it’s happening anyway has led many Remainers to rethink their wariness of independence. Coronavirus has reinforced that trend: the feeling that the UK is in the hands of Brexiteer chancers who cannot run a country — and that Scots could do better on their own. Just 21 per cent of voters in Scotland think Johnson has done a good job handling Covid-19, whereas 74 per cent think Sturgeon has done well. Even Scottish Tory voters, by a margin of 44-38, give the First Minister a passing grade. Communications, and not making unforced errors, are crucial.

In such circumstances, it is little surprise that the SNP are on course to win a thumping victory at next year’s Scottish parliament election. Sir John Curtice calculates that, on current polling, the nationalists will take 74 of Holyrood’s 129 seats. If so, with the Greens winning nine seats of their own, almost two thirds of the next Scottish parliament would support independence.

Even Alister Jack, the Secretary of State for Scotland, has intimated that an SNP victory in next year’s Holyrood elections could pass for a mandate for a second referendum. The Tory campaign will have little choice but to argue that a vote against the SNP is a vote to stop IndyRef2, so the logic of a result such as that suggested by the current polls would be that the people of Scotland will have voted for that referendum.

Boris Johnson is duty-bound to ignore any such demand, not least since the available evidence suggests he might very well lose that referendum: he would hardly wish to be the man who delivered Brexit but presided over the dismemberment of his own country. But saying ‘No’ is not a strategy for the long term. At some point, the political and moral pressure to concede a fresh plebiscite on independence will prove irresistible. The longer the question is delayed, the more reasonable it appears.

Poll-reading is an increasingly gloomy business for Unionists. According to a recent Panelbase poll for the Sunday Times, two thirds of voters under the age of 34 favour independence, as do a clear majority of voters under 54. Independence is not inevitable, but the idea it may be is powerful. Each year the Scottish electorate becomes a little less British and a little more Scottish. It is a question of identity, not economics. As such, it’s hard to argue or campaign against. It’s harder still now the Tories no longer have Ruth Davidson as their main campaigner. Her successor, Jackson Carlaw, has already fled rather than face the coming battle. Douglas Ross, the latest Scottish Tory leader, isn’t even in the Scottish parliament (he sits for Westminster).

So viewed from a purely Unionist and non-partisan perspective, a Labour government would be welcome. Half of Labour’s supporters in Scotland at present favour independence, and the Labour vote is the crucial demographic that might yet determine the UK’s fate. A Labour party that is electable in England is the Labour party best placed to recover in Scotland too; it might help persuade left-wing and working-class Scots that independence is not the only way to get rid of the Tories. But such a revival is a long way off.

The chief threat to Sturgeon’s future does not come from the crippled opposition at Holyrood. Nor is there much to fear from the present UK cabinet. Instead, her largest non-coronavirus problem is her predecessor. This spring, Alex Salmond was acquitted of all 13 charges made against him. He has since vowed to avenge himself on those he believes have wronged him. Sturgeon is at the top of that list. Salmond believes he was the victim of a dirty-tricks campaign designed to thwart any prospect he might have of returning to front line politics.

A Holyrood inquiry is charged with exploring the detail of the Scottish government’s own investigation into complaints made against Salmond, and some of those close to the former first minister believe Sturgeon repeatedly misled the Holyrood parliament about what she knew, and when, about the Salmond affair. Would Salmond really risk doing untold damage to the movement to which he has dedicated his life, at a time when its prospects of ultimate success have never been greater? Remarkably, the available evidence suggests that he would.

This is a thin — and, frankly, tawdry — straw for Unionists to clutch. But right now it may be the best straw available. The SNP seems politically immune to its own failings on Covid and public services, but it is vulnerable to itself. For just as this mess is of the British government’s own making, so the SNP’s internal divisions may do the nationalist cause more damage than anything Sturgeon’s outside opponents can throw at her.

Enjoy your holiday, Prime Minister.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

spectator.co.uk/podcast - Alex Massie on the threat to the Union.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in