Arena: The Changin’ Times of Ike White (Monday) had an extraordinary story to tell — but one that, halfway through the documentary, already seemed to be complete. So, you might well have thought at that point, how would it fill the rest of the time? The answer, it transpired, was by taking an even more jaw-dropping turn.

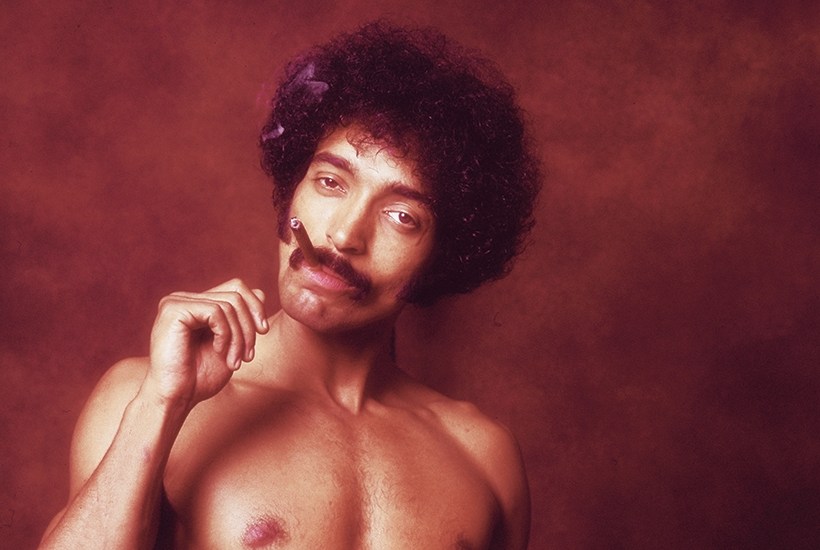

In the 1970s, Ike White was serving life for murder in a Californian prison when reports of his musical talent reached the record producer Jerry Goldstein. A prodigy on guitar, bass, drums and keyboards, White had until then been making most of his music in the prison’s gas chamber, which he was allowed to use as a rehearsal room. Now Goldstein brought in a state-of-the-art mobile studio and recorded White’s album Changin’ Times, released in 1976.

From what we heard — and were told by some veteran soul musicians — it was a brilliant amalgam of soul, rock, funk and blues, with guitar work that Jimi Hendrix might have been proud of. ‘He could have been a big star,’ said Goldstein, especially when CBS offered to turn White’s story into a TV Movie of the Week. The trouble was that White refused to let anybody play him on screen except him and, as Goldstein pointed out, ‘that was never going to happen’. As a result, the two men parted, and the album faded into obscurity. But not before it had impressed Stevie Wonder enough for him to get White a new lawyer, who secured his release in 1978, aged 32.

While in jail, White had married Goldstein’s 19-year-old secretary, Deborah, who’d grown up on a farm in Colorado and was waiting for him at the prison gates. Speaking on the programme, she remembered him with both affection and exasperation at his tendency to ‘make choices that made things very difficult’. (Cue photographs of her husband with an assortment of young lovelies.) At the third attempt, she finally left him for good. And with that, White himself disappeared.

Until, that is, a few years ago when the documentary’s director Daniel Vernon tracked him down to San Diego. At least three name-changes later, White was a somewhat cheesy all-round entertainer called David Maestro (‘Book Maestro now for your next special event’) and married to the Russian Lana. ‘I met him and I fell in love and I’m very happy,’ Lana beamingly explained — a contentment David seemed to share as he rolled a large joint of medical marijuana and told Vernon anecdotes of varying believability about everything from that murder he accidentally committed when the gun went off in his hand to marching behind Martin Luther King in Atlanta, arm in arm with a rabbi and a nun. ‘Why are you telling your story now?’ asked Vernon. ‘Because I’m getting old,’ David replied — the halfway point at which the programme appeared to have discharged its duties.

Shortly afterwards, though, Lana returned home to find that David had hanged himself. He’d also left behind enough letters, photos and home movies to fill several storage lockers. So it was that she discovered a bafflingly lengthy trail of abandoned women and children, some of whom the programme talked to. One daughter, for example, recalled that she’d first heard from him when, much to her excitement, he rang on her ninth birthday — but never made contact again. There was also the time (again with home movies to prove it) when he’d lived in a retirement community with an 86-year-old woman he called ‘Mum’.

But perhaps odder still, Lana and some of his other women then got together, and we watched them exchanging almost fond tales of his many lies and betrayals. (One was rather touched that a later Ike woman looked like her when she’d first met him.) Just as indulgently, they ascribed most of his behaviour to his sensitive and artistic nature. And so, on the whole, did the programme itself, which ended with a clip of Ike/David at his most charming as he sang a little acoustic number to an effusively grateful Vernon.

Only later, in fact, did something more unsettling occur to me: would Ike/David have committed suicide if the film-makers hadn’t shown up? After all, this was a clearly disturbed man, who’d never adjusted to post-prison life, and had successfully hidden away for decades. Now here he was, faced with a film crew, albeit a well-intentioned one, who wanted to find out and broadcast the truth about him.

If the same possibly unfair thought ever occurred to Vernon, his documentary gave no sign of it. Nonetheless, it did mean that after finishing the programme in a state of riveted admiration for it, I’m now wondering if this was also one of the more troubling examples of television creating the reality that it claims merely to be depicting.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in