An incurable disease … highly contagious… those struck down by it shunned by neighbours and friends… its cause unknown … the death toll rising. A description advanced during the AIDS epidemic but one that also fits virtually every epidemic and pandemic that we have experienced over the last 200 years including the current coronavirus outbreak.

Every virulent outbreak of infectious disease that Australia has experienced carried with it not one but two epidemics – the physical manifestation of the disease itself represented by cases and deaths and our psycho-social reaction to it- denial at first followed by fear, hysteria and panic, a search for someone to blame, an on-rush of commercial and media exploitation and finally, though not always successful, our government and health authorities reaction usually reaching back into the past for a raft of measures related to quarantine, isolation, border controls, cleansing and disinfecting.

Ever since SARS struck, we were repeatedly told that a pandemic was coming, and coming soon. It might be flu or perhaps a new viral infection nurtured in wild animals in Asia, but whatever it was we were told it was coming. And the in 2009 the WHO finally accorded Swine Flu official pandemic status and it appeared that our worst fears were realised. “Pandemic” fast became the buzz word of the 21st century. It remains extraordinary how easily we are panicked by the threat of a pandemic and how small a part knowledge of past epidemics and pandemics plays in our memory.

Epidemics of infectious disease have been a deep-seated and inescapable feature of Australian life since the early days of settlement. Over the last 200 years, the lives of many Australians have been swept up in outbreaks of infectious disease. Such episodes brought home the message for many Australians that infectious disease was an inescapable feature of the insecurity of everyday life and a regular reminder of the ubiquitous presence of death and disease.

Although many of these epidemic encounters were often short-lived and for the most part not great demographic crises, they nonetheless had tremendous impact and their effects were wide-ranging. But how quickly we forget such things and how little we have seemed to have learned from experience. The last great plague pandemic which swept out of China in the 1890s and affected Australia in 1900 caused thousands of Australian cases and more than 530 deaths. The dengue epidemic of 1925-26 remains the most significant and most widespread outbreak in Australian history. Over four months the outbreak caused 600,000 cases and 147 deaths. The epidemic stretched all the way down the eastern seaboard of Australia and in many coastal towns between 70 and 80 percent of the population caught the disease. The polio outbreaks between 1903 and 1956 also left an indelible imprint on Australia. For more than 50 years the disease struck seemingly at random affecting more than 100,000 Australians.

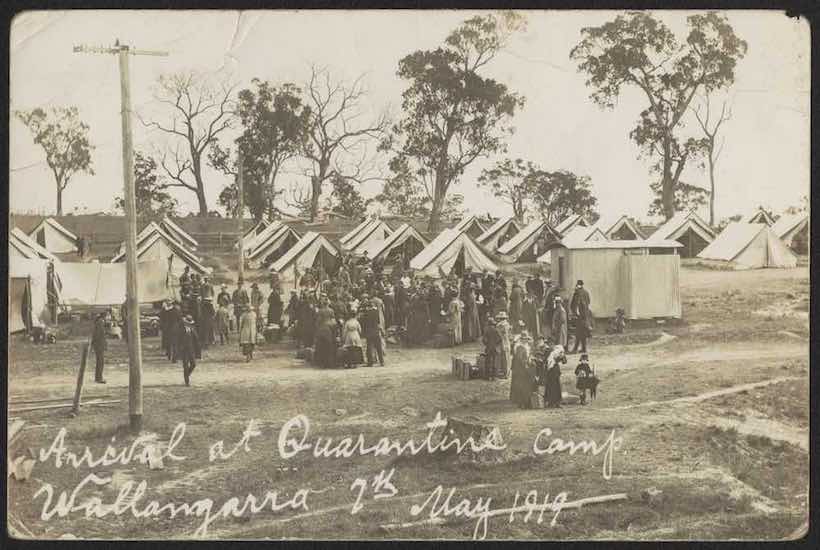

The 1918-19 influenza pandemic stands as one of the great natural disasters of all times. In Australia, the pandemic was a major demographic and social tragedy affecting the lives of millions. In six months in 1919 more than 15,000 Australians died of flu and more than two million caught the disease. In Sydney just under 40 per cent of the population caught flu and more than 4,000 died.

There seems little doubt that we are better prepared to confront infectious disease today than we were 50 or 100 years ago although our experience of SARS, Avian Flu and now coronavirus suggests that we still have much to learn and show that public fear and hysteria can easily overwhelm even our best-laid plans. There is little doubt that advances in medicine has seen the relatively quick development of vaccines and anti-viral drugs. As well global surveillance systems are much more developed as well as pandemic plans being developed by many governments including Australia highlighting things like surveillance, rapid identification, travel restrictions, quarantine and isolation and public closures.

And now the bad news. Firstly, we still seem unable to fully appreciate the significance of the microbial world and its ability to adapt and change against the drugs we level against it. We continue to believe that we are the dominant species on earth and that when a microbial threat confronts us, we can simply develop a magic bullet, and all will be well. Nothing could be further from the truth. One of the crucial messages to emerge from the emergence of infectious disease is that the biophysical environment is a powerful ever-changing force and that we have severely underestimated the role it plays in our lives with respect to infectious disease.

Secondly, we continue to believe that our Government can protect us and fully understands the nature of the threat and is equipped with plans and drugs to keep us safe. And then we need to confront the wave of fear, hysteria and panic that accompanies the pandemic. How would our government manage such things? Most of the official pandemic plans are silent on the issue. There is little doubt that governments and Medical Authorities do not fully appreciate how ordinary people see infectious disease threats in their lives and how they regard risk. Risk to governments and medical authorities is a definable, measurable phenomenon, simply arrived at by taking the numbers of those exposed to the pandemic as a percentage of the total population. But risk is far more than this. To you and I risk is an emotional, psycho-social phenomenon influenced by the people around us and how we see the local world and react to opinions and behaviour around us. Many of us also harbour deep-seated fears about infection and contagion which are a mix of rational and irrational fears. If friends and neighbours are fearful and stockpiling food and other essentials, then we too will become fearful and follow suit. In all this media and Government pronouncements play a critical part, not only informing and advising us but also critically raising our fear.

Governments probably think that a certain amount of fear in useful in raising our awareness and encouraging us to adopt precautionary measures. But beyond that Governments rarely address or understand the fear side of pandemics. Finally, can we expect our Government to contain the pandemic. Official policy is usually that the Commonwealth takes over responsibility for managing an infectious disease outbreak and can put in place specific border controls, quarantine and isolation procedures as well as other measures. In Australia dealing with pandemics such as the coronavirus calls for cooperation between the various levels of government; local, state and territories and the Commonwealth. The assumption is that all will work together to address the infectious disease threat. Yet Australian history is littered with examples of the lack of cooperation, self-interest, ignorance, over-reaction and antagonisms during epidemic and pandemics.

The 1908 Quarantine Act gave the Commonwealth power over internal quarantine throughout Australia and while the Commonwealth stated a year later that it was not their intention to make use of such power with regards disease outbreaks in 1913 when smallpox broke out in Sydney, Cumpston the Commonwealth Director of Quarantine unilaterally declared the area within a 15-mile radius of the Sydney GPO a formal quarantined area without any reference to the NSW Government. Such a proclamation produced a violent reaction in Sydney. The NSW Premier clearly stated that NSW Health officials would be reluctant to take orders from Commonwealth Officers and Sydney’s business community were equally as hostile.

The 1918-19 influenza epidemic provides another example of the lack of cooperation between the Federal and State Governments. In 1918 faced with a growing influenza epidemic around the world the Commonwealth Government convened a conference of all States and Territories to address the growing threat. All agreed to a 13-part plan whereby the Commonwealth Government would be notified immediately flu broke out in any State or Territory and then assume authority and full responsibility for interstate transport, border security and formal quarantine. What happened?

Well in 1919 when the first cases of influenza appeared in Melbourne the Victorian State Government delayed informing the Commonwealth for some weeks for fear that quarantine might affect local businesses by which time the disease had spread to NSW. South Australia also initially refused to notify the Commonwealth of any cases. Once influenza was officially declared in Victoria, NSW closed its land and sea borders and put in place its own quarantine and border security procedures. From here it was every State for itself and the Commonwealth Agreement of 1918 went out the window. All States set up their own quarantine and border controls and bitter disputes between the States and the Commonwealth took place.

Tension rapidly escalated between Victoria and NSW. Victoria threatened reprisals against NSW and both States set up their own border quarantine camps with their own set of regulations. There were also clashes over the return of Australian troops from Europe. Queensland refused to let the troops ships land and eventually was taken to the High Court by the Commonwealth who won the case. Tasmania engaged in a bitter dispute with the Commonwealth over the quarantine period for interstate shipping and Western Australia threatened to secede from the Commonwealth over the suspension of the intercontinental train link. Eventually, the Commonwealth was forced to withdraw from all activities except where they involved sea traffic. State rivalry also came to the fore in 1921 when plague broke out in Brisbane. On September 13 of that year Queensland officially notified the Commonwealth Department of Health of a death from plague three weeks earlier. The Commonwealth immediately notified all States, but it was too late, and plague broke out in Sydney having been introduced by an interstate ship from Brisbane. But it was not simply disputes between Governments that influenced the progress and outcome of epidemics and pandemics. The 1925-26 dengue epidemic reveals the importance of how ordinary people viewed outbreaks of infectious disease.

There is a long history in Australia of people resenting the imposition of rules and regulations by governments even when advanced for the control of infectious diseases. During the 1925-26 dengue epidemic in NSW Local Government Ordinance 41 provided local authorities with the power to inspect homes and enforce mosquito control by the removal of rubbish and the screening of water tanks. Local government workers had to combat vested interests, disinterest, outright opposition and backsliding. Some local councils even refused to adopt such measures such as West Maitland and suffered a resurgence of dengue. Within six months after the epidemic ended many homes in Northern NSW and Queensland had simply slipped back to pre-epidemic days of unscreened water tanks. Given all this can we have any confidence in all the states and the commonwealth cooperating to confront the coronavirus as well as ordinary people understanding the nature of risk?

Maintaining the public’s health in Australia during times of epidemics and pandemics requires a deft balancing act – of balancing the overall wellbeing of all Australians against the individual’s rights and freedoms – an exceedingly difficult undertaking even in the best of times because there is a basic conflict between the two. In times of pandemic crisis, it often becomes almost impossible. It is interesting how we struggle with this dilemma – of how a society committed to the supremacy of civil liberties and human rights and sensitive to discrimination can reconcile the conflict between individual rights and the common good.

Currently, we are experiencing just this as the States and the Commonwealth struggle to impose a wide range of border controls, quarantine and isolation procedures and widespread shutdowns and closures. In addition, we have much to learn from the way we responded to earlier epidemic and pandemic crises. They provide many insights into how authorities faced the threat of infectious disease and how the general public reacted. There is little doubt that major pandemics call for cooperation between all levels of government – local, state and Commonwealth. Despite current confidence, such things cannot be taken for granted. Australia’s history is littered with examples of lack of cooperation, of self-interest, ignorance, over-reaction and outright antagonisms as the States and Territories were undermined by the Commonwealth Government of went their own way in a form of defiance.

Pandemics are as much psycho-social events as they are epidemiological ones. Regrettably, as I have stated Governments have not always recognised this. In the final analysis, the study of the impact, diffusion, effects and reaction to past pandemics and epidemics should be a rewarding experience. In the first place there is a need for retrospective studies of the behaviour of different people exposed to major outbreaks of infectious disease. In the second place, close observation of the way people and communities respond during times of crisis can reveal much about social attitudes, patterns of activity and behaviour as well as highlight underlying tensions, conflicts and antagonisms. Thirdly, living in pandemic times may result in significant changes in human values, attitudes and behaviour and ultimately lead to important changes in public health. Fourthly, if we don’t learn from the past, if we simply dismiss what happened as part of an earlier less scientific age, then we run the risk of repeating the mistakes made. Let us hope that we can apply some of this to our approach to the coronavirus.

Finally, pandemics, as the coronavirus demonstrates, are not simply a thing of history. They continue to happen and underscore just how fragile our relationship is with the biophysical environment; how closely human and animal health are linked and how much we rely upon human behaviour to protect us.

Illustration: National Museum of Australia.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in