Months ago, not long after Boris Johnson’s 2019 general election triumph, I wrote a Times column of a cautiously hopeful nature about his prospects in Downing Street. The column was in reaction to well-sourced reports that Mr Johnson’s management philosophy was to encourage ministers to get their heads down and get on with the job, to avoid the TV sofas and broadcasting studios unless there was something important to get across, and not to suppose that media exposure should be equated with career success.

There was a view widespread at the time that Johnson would treat the governance of the United Kingdom as he had (as mayor) treated the governance of London: an occasional touch on the tiller, a benign presiding presence, but a disposition to appoint competent people to the big jobs, trust them and let them get on with it. Johnson would be the ultimate generalist: broadly across the policy and his ministers’ work, and ready to set overall direction, but no micro-manager.

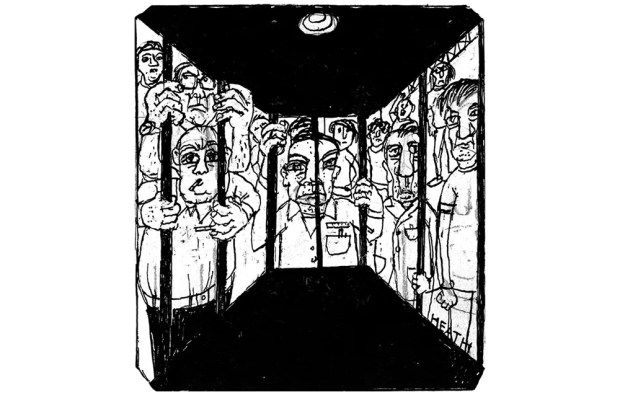

I really liked the sound of this, and said so. The style played to some of Johnson’s strengths: an impression of good nature and goodwill, an air of positivity and optimism, a commanding presence and a vague but appealing sense of reasonableness, tolerance, humour and humanity. Thus he would float above mere administration, displaying, in the words of that 1980s Czech novel’s title, the Unbearable Lightness of Being. Of being Prime Minister, in Boris’s case.

And not only did this play to some of his strengths, it played to one of his principal weaknesses, inattention to detail. In the role envisaged, Johnson didn’t need to be a details man.

Behind the appeal of this ‘chairman of the board’ theory of Downing Street management, however, must lie three important assumptions. First that the individuals to whom the PM deputes day-to-day decision-making are highly capable managers. Second, the PM himself maintains a good, broad grip on overall direction, and a grasp of the essentials if not the details of policy. There’s a world of difference between standing back and leaving the field. And third, that the PM is decisive and brave when he needs to be.

Since then, Boris Johnson has been doing a great job of being hands-off, but so did Nero. I lose confidence that our new Prime Minister possesses in sufficient measure those three qualities of intellectual penetration, practical grip and moral courage; and the unedifying tale of Priti Patel and her permanent secretary are illustrating this in dramatic fashion.

Of course there will be some Spectator readers and some in the parliamentary Conservative party ready to conclude that she’s a capable, bold and radical minister determined to shake things up at the Home Office, fighting valiantly against the do-nothing Sir Humphreys of the Whitehall mandarinate. I am unlikely to persuade such onlookers that Ms Patel really is as dreadful as has been reported, and anyway I have it only on hearsay: I was not there in the room, and nor were any of my colleagues in journalism who have reported on such scenes, when the Home Secretary did (if she did) shout and swear, ridicule and intimidate. This kind of journalism is necessarily hearsay. But the witnesses (and I know who many of them are) are too many and too credible for me to dismiss all the reports as tittle-tattle.

As to Sir Philip Rutnam, I do not know him; but I know Tory ministers, special advisers and civil servants who worked in the Transport Department when he was the permanent secretary, and have never heard anything to suggest he was the poisonous and obstructive troublemaker that some of Patel’s supporters seem to be putting about. Quite the contrary.

Whether, however, we’d be right or wrong to suppose Sir Philip the injured party here, these are the allegations, and they’ve been made repeatedly and with force. Quite early on, long before matters reached the point they did last weekend when Rutnam resigned in so sensational a way, Johnson (who will have heard them) should have instructed the Cabinet Secretary, Sir Mark Sedwill, to investigate and report. Perhaps he did, but if so then the report would surely have been that a big problem was looming here. That was the moment when a decisive occupant of No. 10, however hands-off, would see the need for hands-on. And you can be fairly sure that Patel would have done anything the PM told her.

Now it’s all too late. Not only is the damage done, but there’s more damage to come. Rutnam says he’ll take legal action against the government for unfair ‘constructive’ dismissal. Given what I’d expect to be the available evidence, an employer would at this point probably settle out of court for a substantial sum, hopefully (for the employer) on ‘non-disclosure agreement’ terms. Then the employee would pocket the money and every-body would agree to shut up about it.

But the problem for the employer in this case is that a substantial sum has already been offered (suggests Rutnam) — and refused. And a non-disclosure agreement would be a curious thing given how much has already been disclosed (or alleged), and given, too, Rutnam’s insistence that it’s partly in order to protect his staff from further bullying that he has gone public in this way.

Further, given that Patel absolutely denies all the allegations, any decision by government to settle out of court would look odd indeed, and would attract new criticism and new headlines: after all, we taxpayers would be being asked to give a former top civil servant a lot of money to drop a case against a minister who insists the case is baseless.

She’d have to go. And Johnson was presumably saving up her dismissal for when his and her new immigration regime stumbles. Oh dear. There’s a fine line between hands-off and losing your grip, the Prime Minister has fallen the wrong side of it, and the unbearable lightness of being Boris Johnson is proving — well, unbearable.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in