I could list all manner of things I don’t try, because I know I won’t like them, like skydiving and revolting cocktails. But there’s another list of things I don’t try, knowing I might like them just a bit too much. ‘Puzzle Rush’ was, for some time, in the second category. Chess.com is one of the websites where people go seeking out internet games, and their release of ‘Puzzle Rush’ in late 2018 was an instant hit. The challenge is to solve as many chess puzzles as you can in five minutes. The puzzles get gradually harder, and after three strikes, you’re out. It goes to show that even games can be gamified, and many found this virtual chess whack-a-mole ludicrously addictive. Eventually curiosity got the better of me.

It was fun, and a rush was certainly to be had from the blend of frantic clicking and wide-eyed attention in this new flavour of online speed chess. But there is more ‘rushing’ than ‘puzzling’. With the clock ticking down, it’s hardly possible to immerse yourself in the puzzle, or pause to savour its beauty. In my experience, the finest chess puzzles deserve to ferment in the mind, and be consumed sparingly.

That must be part of the appeal of formal solving competitions, which have existed much longer than ‘Puzzle Rush’. The final of the Winton British Chess Solving Championship is conducted over several hours in the manner of a written exam, with a series of puzzles grouped into stages. The 2019/20 edition concluded last month, and was won by John Nunn, a three-time world champion. He finished ahead of Jonathan Mestel and David Hodge; this trio made up Great Britain’s bronze-medal winning team at the World Championships held in Lithuania last year.

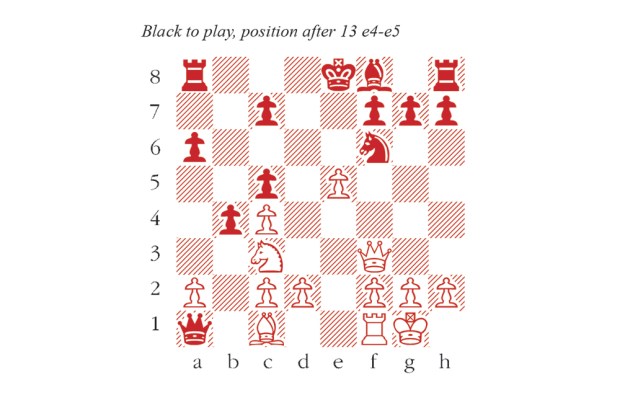

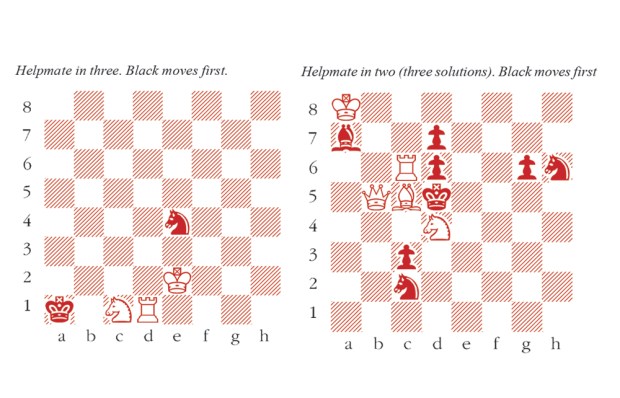

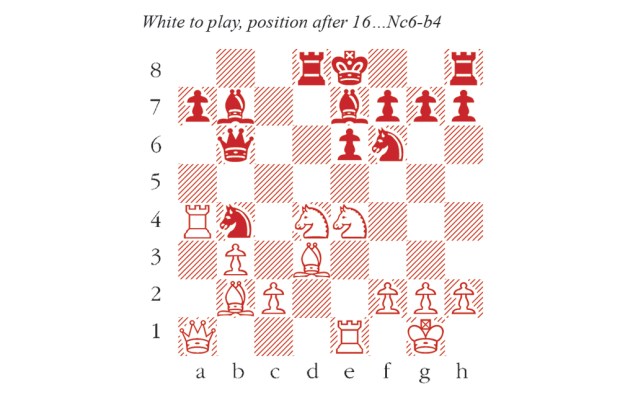

There is an elaborate taxonomy of chess problems — mates in two, mates in three or more, studies, helpmates, selfmates and more. They can be fiendishly challenging, even for experienced solvers, though ‘over-the-board’ players often favour studies, since the concepts correlate most strongly with those seen in practical play.

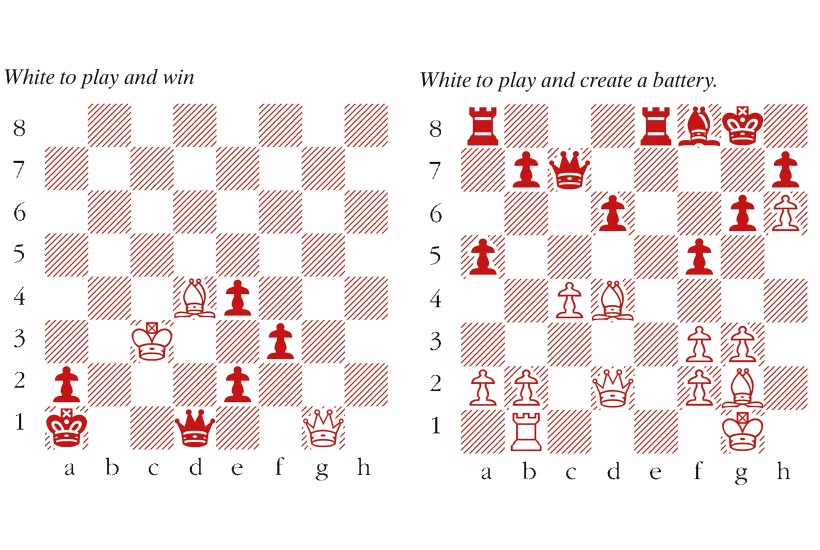

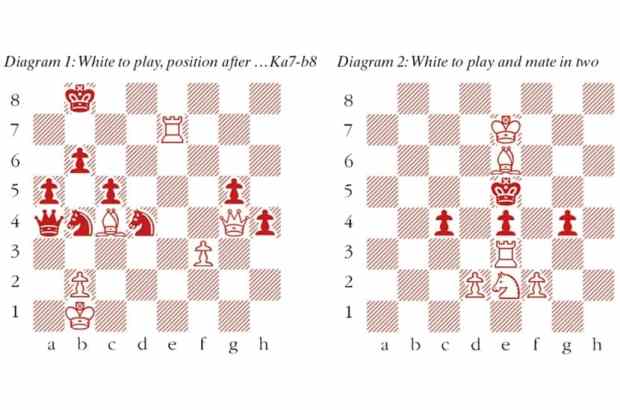

The first diagram shows the climax of a 1986 study by the Russian composer Oleg Pervakov. White to play wins with the extraordinary 1 Bh8!!, preparing to meet 1…Qxg1 with 2 Kc2+, and mate follows on the long diagonal. Or if Black plays 1…Kb1, then 2 Qg1-b6-b2 delivers mate. While if Black plays 1…f2, we find out why h8 was the right square for the bishop: 2 Qg7! creates a decisive battery on the long diagonal, e.g. 2…e1=Q+ 3 Kc4+ Kb1 4 Qb2 mate.

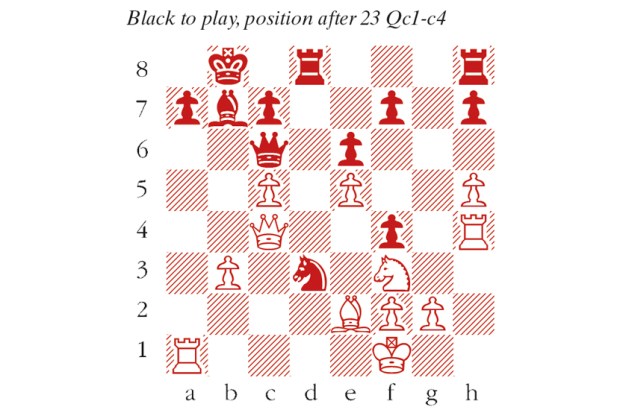

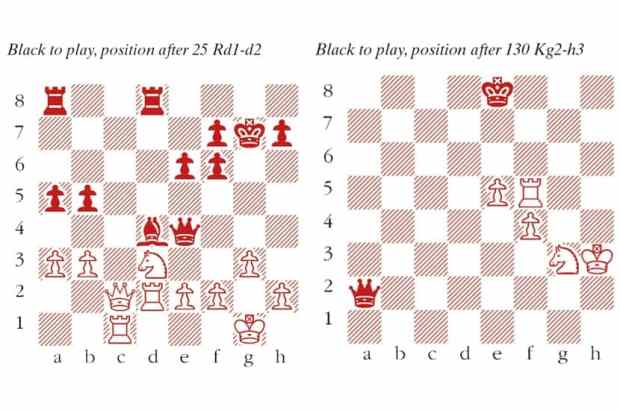

Fashioning a battery by withdrawing a bishop is a technique worth remembering. The second diagram is taken from the game Carlsen–Yuffa, Doha 2015. Carlsen has clear compensation for the exchange, and now he prepared a decisive battery on the long diagonal by withdrawing his bishop. 23 Bc3! prepares Qd2-d4, so 23… Qxc4 24 f4 threatens Bd5+. Re4 25 b3 Qc5 26 Ba1! White insists d5 27 Rc1 Black resigned, e.g. 27…Qd6 28 Bxe4 fxe4 29 Qd4 wins.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in