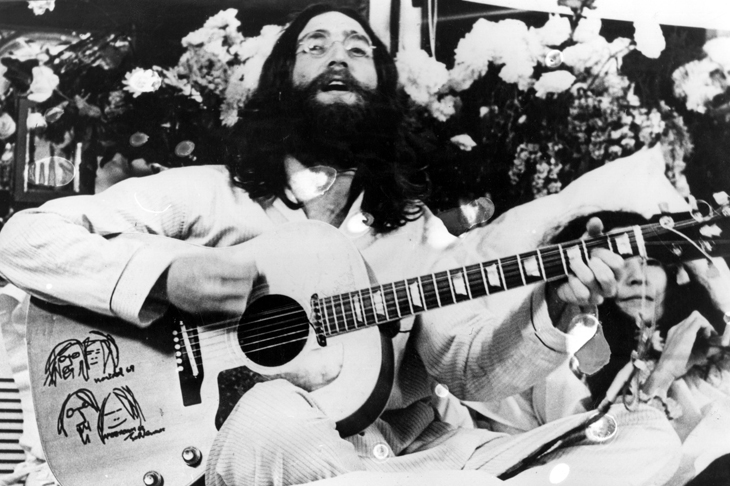

‘A very merry Christmas,’ sang John Lennon in 1971, ‘and a Happy New Year; let’s hope it’s a good one, without any fear.’ Since most of Lennon’s fears would have been tax related by then we can assume that the ones he was referring to are the sort which affect people from a different income bracket and specifically, people living in places ravaged by warfare, famine and disease.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in