Great biographies try to answer questions about the complicated relationship between their subjects’ inner life and outer workings. How did Winston Churchill turn the pain of his early life and his years in the political wilderness into the words that galvanised the free world? How did Frida Kahlo’s physical impairment shape her vision as a painter?

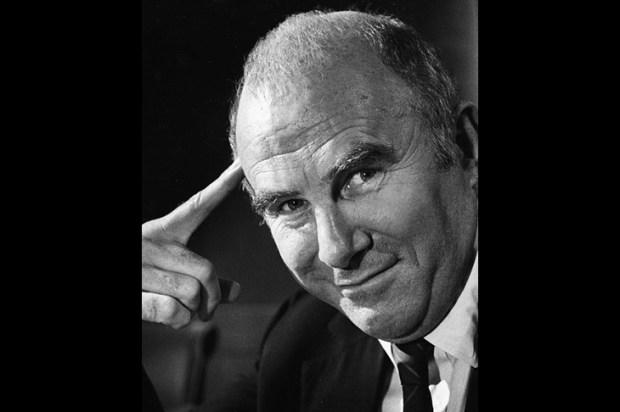

I am endlessly interested in the inner and outer lives of the African–American writer and activist James Baldwin, for my money not just the most important black writer of the past 100 years, but one of the most important American writers ever. Although we differ wildly in our life experience — I am a straight white Christian male raised in the American South, Baldwin was a gay black man from Harlem who left organised religion behind — I find such wisdom in his essays, such beauty in his fiction, that I continue to wonder how he mined his own particular experience as a way of helping to illuminate mine, and I am always wanting to know more.

In this new biography, Bill V. Mullen employs Baldwin’s ever-evolving radical politics as a way of exploring what he wrote and what he said. I feared at first this might be a limiting way to understand him (I’d like to think we are all more than the sum of our expressed political beliefs), but it actually serves as a useful filter to approach the life and art. Since political beliefs do grow out of personal experience, Mullen uses Baldwin’s politics as a way of reverse engineering him to illuminate why he does what he does.

Since he was a great artist, Baldwin’s writing, speaking and activism were, on the one hand, universal, but they were clearly also identity based. William Faulkner once said that all great writers explore universal themes from their own ‘postage stamp of land’. Baldwin’s tiny scrap of land was distinctive: he fled Harlem for Paris, Turkey and the south of France, hoping to find the love, acceptance and peace he could not know in America.

But because he was a gay black man with a conscience (and, Mullen argues, a feminist, an anti-imperialist and pro-Palestine), he could not sit safely in exile while he witnessed injustice at home. Like Dr Martin Luther King, Jr., whom he met, admired and wrote about, Baldwin agreed that injustice anywhere was a threat to justice everywhere. He sought to express a vision of post-racism, of a world where one’s sexual desire would be less important than love and connection, a vision of a world turned upside down.

Mullen successfully positions Baldwin as a radical writer, one who believed that the house needed to be burned down and who also said that love and reconciliation were the only solutions to the divisions he witnessed. His advice to his nephew in The Fire Next Time (1963) was that although it was unfair and would be supremely difficult, his nephew would have to love his white oppressor, would have to recognise that white men and women were trapped in and by their own awful history, would have to understand that only by working with those who hated him could black and white people emerge into a new light of freedom. Baldwin’s is a radicalism that draws from Marx, yes, but that also remembers how Christian radicals from Jesus onwards gave themselves in love for a world on fire. He may have left the Church, but the Church remained in his blood and in his bones.

James Baldwin: Living in Fire is one of a series of short biographies published by Pluto Press on important radicals (other volumes consider Allende, Gandhi and Sylvia Pankhurst), and Mullen himself is a writer and teacher known as a champion of radical politics. The book could have been a mere protest pamphlet, but it is much more than that.

Baldwin made his literary reputation condemning protest literature by Harriet Beecher Stowe and Richard Wright, literature shaped more by the writer’s politics than by a universal concept of art and humanity. And while he cared deeply about civil rights, queer advocacy and the Palestinians, his writing and speaking resonate with even those who do not look, believe or love as he did. My students, whether gay, straight, black or white, have certainly found themselves in Baldwin’s work, as have I. His postage stamp of land enabled him to speak to the issues of his day and of ours, to offer answers to the big questions with which every one of us wrestle.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in